5.5 GLOBALIZATION AND DEVELOPMENT

GEOGRAPHIC INSIGHT 2

Globalization and Development: After the fall of the Soviet Union, economic reforms and globalization changed patterns of development in this region. Wealth disparity increased and jobs were lost as many Communist-

When the Soviet Union disbanded in 1991, there was a disorderly transition to a market economy that gave the advantage to a small number of well-

privatization the sale of industries that were formerly owned and operated by the government to private companies or individuals

oligarchs in Russia, those who acquired great wealth during the privatization of Russia’s resources and who use that wealth to exercise power

The transition to a market economy took place so rapidly that it was known as “shock therapy.” A wide range of policies attempted to revitalize the sluggish economy by moving as quickly away from the old command economy as possible. Today, approximately 65 percent of Russia’s economy is in private hands, a dramatic change from the virtually 100 percent state-

Unfortunately, shock therapy came at steep cost for many Russians. A major part of the reforms was the abandonment of government price controls that once kept goods affordable to all. Instead, newly privatized businesses determined prices in the environment of great uncertainty created by shock therapy. This led to skyrocketing prices for the many goods that were in high demand but also in short supply. While a few people became rich, many lost their savings because of inflation and could barely pay for basic necessities such as food. Toward the end of the 1990s, as opportunities opened and competition developed, the supply of goods increased and prices fell. But even today, the effects of shock therapy are still being felt. For example, Russian economists estimate that even though average incomes have grown by 45 percent since 1991, almost all of this gain has gone to the wealthiest 20 percent of the population; the bottom 20 percent of the population is earning about half what they did in 1991.

Oil and Gas Development: Fueling Globalization

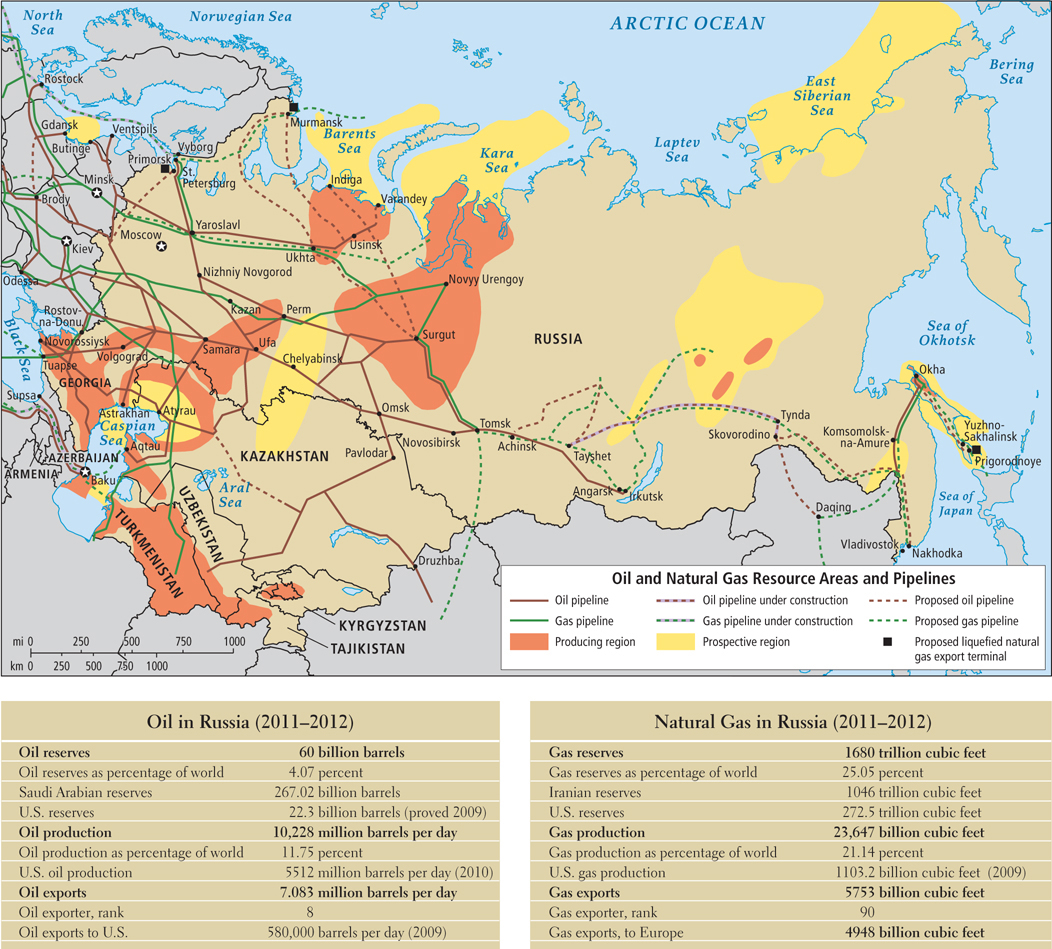

Natural gas and crude oil have emerged as the region’s most lucrative exports, introducing a new wave of globalization and fossil fuel–

By the year 2000, after an initial decade of economic instability, rising revenues from oil and gas began to finance Russia’s economic recovery. In response, Russia’s central government tightened control over the entire oil and gas sector. Today, Russia is the world’s largest exporter of natural gas, and taxes on energy companies fund more than half of the federal budget. While this does guarantee that at least some of the revenues from the new fossil fuel–

Russia’s relationship with Europe is intertwined with the lucrative oil and gas trade. The majority state-

Gazprom in Russia, the state-

In 2009, Russia curtailed Ukraine’s access to Gazprom’s gas in a dispute over prices and as a response to Ukraine moving closer to the EU rather being a Russian ally. Because pipelines that supply Europe with gas run through Ukrainian territory, gas shortages also developed in parts of Europe. The EU became concerned about its reliance on Russian energy and is now rapidly turning to other sources of fossil fuels as well as renewable energy sources. The political dimensions of these issues are discussed further later in this chapter.

Central Asia has yet to find stability because a tug-

Because Central Asia is landlocked, the only way to get oil and gas from there to world markets is via pipelines (see Figure 5.14), the routes of which have become a major source of contention. Russia, the United States, the European Union, Turkey, China, and India have all developed or proposed various routes. A 1900- 108. ENERGY REVENUES AND CORRUPTION INCREASE IN RUSSIA

108. ENERGY REVENUES AND CORRUPTION INCREASE IN RUSSIA

Russia’s Relations with the Global Economy Both the European Union and the United States want to ensure that Russia’s oil and gas wealth does not finance a return to the hostile relations of the Cold War. For this reason, Russia was invited to join the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the Group of Eight (G8), an organization of eight affluent countries with large economies.

Group of Eight (G8) an organization of eight countries with large economies: France, the United States, Britain, Germany, Japan, Italy, Canada, and Russia

Looking to form an economic counterweight to the United States and the European Union, Russia has recently been meeting with Brazil, India, and China to form a trade consortium known as BRIC. All four countries are large, populous, and have had spectacular economic growth over the last decade, making the alliance a symbol of the growing power of the “developing” world. Of the four, Russia’s economy is the slowest growing and arguably the least diverse in the group due to its dependence on fossil fuel exports, but it is also the wealthiest on a per capita basis.

Institutionalized Corruption The cost of doing business in Russia is affected by a high level of corruption. In 2013, the organization Transparency International rated Russia the most corrupt of the BRIC countries and among the most corrupt in the world. With the exceptions of Belarus, Moldova, Georgia, and Azerbaijan, all countries in this region were rated as more corrupt than Russia. Civil servants and the police often expect businesses to offer bribes to receive licenses and to avoid other regulatory hurdles. This affects large corporations and small entrepreneurs alike.

Even those who make it through the labyrinth of setting up a business must then face protection racketeers, as organized crime has become a fact of life during the post-

The Growing Informal Economy A large share of the economic activity in the region takes place in the informal sector. To some extent, the new informal economy is an extension of the old one that flourished under communism. The black market of that time was based on currency exchange and the sale of hard-

Workers in the informal economy tend to be young, unskilled adults; retirees on tiny pensions; and those with only a low level of education. The majority of these workers operate out of their homes by selling, among other things, cooked foods, vodka made in their bathtubs, and clothing and electronics that have been smuggled into the country. The World Bank has estimated that the informal sector makes up about 40 percent of the Russian economy. In the Caucasian countries, the number is as high as 50 to 60 percent. Such large percentages indicate that people may actually be better off financially than official GDP per capita figures suggest.

Despite the fact that the informal economy helps people survive, it is not popular with governments. Unregistered enterprises do not pay business and sales taxes and usually are so underfinanced that they tend not to grow into job-

VIGNETTE

Natasha is an engineer in Moscow. She has managed to keep her job and the benefits it carries, but in order to better provide for her family, she sells secondhand clothes in a street bazaar on the weekends. Asked about her customers, Natasha says, “Many are former officials and high-

Unemployment and the Loss of Social Services Since becoming privatized, most formerly state-

Unemployment figures for the region vary widely. Since 2013, official unemployment rates have been under 6 percent in Russia, and under 9 percent in Ukraine. In Belarus, unemployment is officially only about 1 percent, but actual unemployment may be higher because many remaining state-

underemployment the condition in which people are working too few hours to make a decent living or are highly trained but working at menial jobs

Food Production in the Post-Soviet Era

Across most of the region, agriculture is precarious at best, either hampered by a short growing season and boggy soils or requiring expensive inputs of labor, water, and fertilizer. Because of Russia’s harsh climates and rugged landforms, only 10 percent of its vast expanse is suitable for agriculture. The Caucasus mountain zones are some of the only areas in the region where rainfall adequate for agriculture coincides with a relatively warm climate and long growing seasons. Together with Ukraine and European Russia, this area is the agricultural backbone of the region (Figure 5.15). The best soils are in an area stretching from Moscow south toward the Black and Caspian seas, and extending west to include much of Ukraine and Moldova. In Central Asia, irrigated agriculture is extensive, especially where long growing seasons support cotton, fruit, and vegetables.

Changing Agricultural Production During the 1990s, agriculture went into a general decline across the entire region. In most of the former Soviet Union, yields dropped by 30 to 40 percent compared to previous production levels. This was due mostly to the collapse of the subsidies and internal trade arrangements of the Soviet Union. Many large and highly mechanized collective farms were suddenly without access to equipment, fuel, or fertilizers. Since that time, agricultural output has rebounded but even today it remains below Soviet levels. Russia’s commercial agricultural sector is still characterized by many large and inefficient farms, most of which are now run by corporations. Russians are now heavily dependent on “homegrown” food—

In Central Asia, agriculture has been reorganized with more emphasis on smaller, food-

Farmers in Georgia, favored with warm temperatures and abundant moisture from the Black and Caspian seas, can grow citrus fruits and even bananas; they do so primarily on family, not collective, farms. Before 1991, most of the Soviet Union’s citrus and tea came from Georgia, as did most of its grapes and wine. Georgia still exports some food to Russia, but because of political tensions between the two countries, Georgia is increasing the amount of food and wine it sells to Europe and other markets outside this region.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

GEOGRAPHIC INSIGHT 2

Globalization and Development After the fall of the Soviet Union, economic reforms and globalization changed patterns of development in this region. Wealth disparity increased and jobs were lost as many Communist-

era industries were closed or sold to the rich and well connected. The region is now largely dependent on its role as a leading global exporter of energy resources. Russian economists estimate that even though average incomes have grown by 45 percent since 1991, almost all of this gain has gone to the wealthiest 20 percent of the population; the bottom 20 percent of the population is earning about half what they did in 1991.

Natural gas and crude oil have emerged as the region’s most lucrative exports, introducing a new wave of globalization and fossil fuel–

dependent economic development. The World Bank has estimated that the informal sector makes up about 40 percent of the Russian economy and 50 to 60 percent of the economies of the Caucasian countries.

Russians are heavily dependent on “homegrown” food—

small household plots, gardens, and family farms that produce 59 percent of the total agricultural output on only 20 percent of the arable land.