5.6 POWER AND POLITICS

GEOGRAPHIC INSIGHT 3

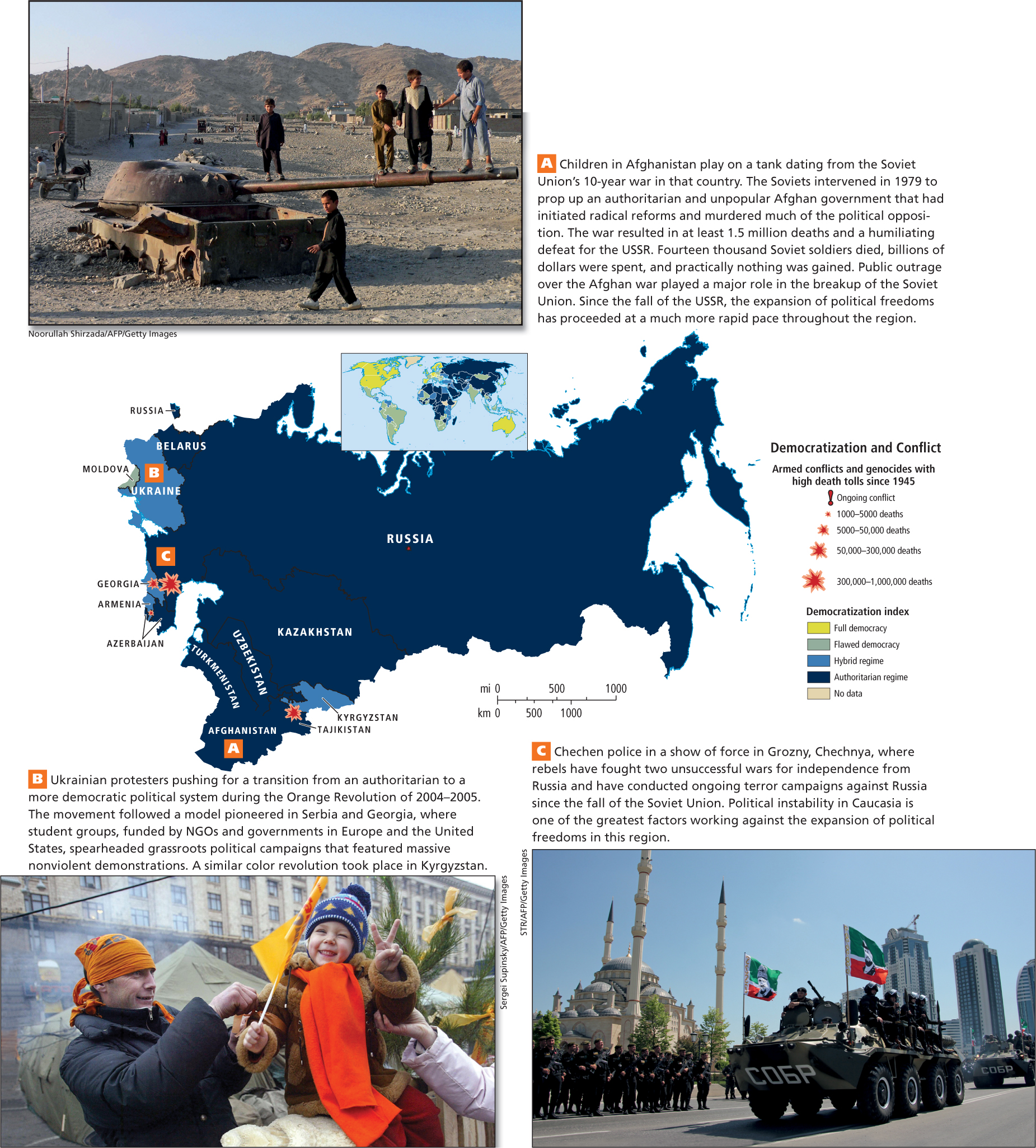

Power and Politics: This region has a long history of authoritarianism. While there is some pressure to expand political freedoms, there are still few opportunities for the public to influence the political process. Elected representative bodies often act as rubber stamps for very strong presidents and exercise only limited influence on policy making.

Since 1991, the politics in this region have remained very authoritarian and largely dominated by Russia, which sees itself as the successor to the Soviet Union. For almost two decades, Russia’s political scene has been dominated by one person, Vladimir Putin, a former high official in the KGB. Putin was elected president in 2000 and has been the country’s de facto leader as either president or prime minister ever since. During this time, he has exercised tight control over political and economic policy and consolidated political power in Moscow. He has been popular for bringing more peace and prosperity to Russia and for restoring Russia’s image of itself as a world power. Putin has also been criticized for preventing meaningful reforms at the local, state, and national levels, and for extending government control over the press and the media. While criticism of the government is now formally allowed, most fear that such criticism would be met with retribution from the securocrats or siloviki (former FSB functionaries loyal to Putin) who control many governing institutions.

Putin is the most dominant political person in the region, and is likely to remain in power for the near future. But long after he goes, authoritarianism will likely hold sway in this region. For one thing, Russia’s current constitution, written in 1993, gives sweeping powers to the president, which will mean that a strong, and likely authoritarian, leader will succeed Putin. Many scholars of this region have argued that Russia’s geography, featuring vast territory and few mountain or other barriers to prevent invasion by outsiders, favors a single powerful authoritarian ruler with a strong military.  117. PUTIN CONFIRMATION

117. PUTIN CONFIRMATION

Elsewhere in the region, authoritarianism and the limited political freedoms it allows are the norm. Belarus, Ukraine, Moldova, the Caucasian republics (including Chechnya, discussed later in this chapter), and Central Asia are still most often run by authoritarian leaders who are unaccustomed to criticism or to sharing power (see the map in Figure 5.16). Elections often involve systematically intimidating voters and arresting the political opposition.

THINKING GEOGRAPHICALLY

Use the Photo Essay above to answer these questions.

Question 5.13

A How did the USSR’s war in Afghanistan ultimately contribute to democratization in the Soviet Union?

Question 5.14

B Who funded the color revolutions?

Question 5.15

C How does Russia’s unwillingness to let Chechnya secede relate to fossil fuel resources?

The Color Revolutions and Political Freedoms In a few of the post-

The color revolutions include the Rose Revolution in Georgia (2003–

In Ukraine, the Orange Revolution took place during the presidential elections of 2004. A candidate who favored closer ties with Russia, Viktor Yanukovych, won the election, but the results were so obviously rigged by the government that widespread protests went on for months. The protests, combined with international pressure, resulted in a new vote in which Victor Yuschenko, who favored closer ties with the European Union and Ukrainian membership in NATO, won.

In subsequent elections, however, the pro-

Crisis in Ukraine In early 2014, one of the most challenging crises this region has seen since the fall of the Soviet Union emerged in Ukraine, pitting Russia against the EU and the United States in a seeming throwback to the days of the Cold War. After Yanukovych backed away from previous commitments to increase economic ties between Ukraine and the EU, a wave of protests developed in Ukraine’s capital of Kiev. Like the color revolutions, these protests were supported by U.S. and European governments and pro-

Regardless of the eventual outcome of the ongoing confrontation between Russia and Ukraine, underlying tensions will remain. Ukraine’s government will be challenged to balance the demands of citizens in the western parts of the country, many of whom want closer ties with the EU, with those of ethnic Russians in the east who want closer ties and possibly even political union with Russia. Russia will have to weigh the economic benefits of its gas trade with Europe against its long-

Cultural Diversity and Russian Domination Russia’s long history of expansion into neighboring lands has left it and neighboring countries with exceptionally complex internal political geographies. As the Russian czars and then the Soviets pushed the borders of Russia eastward toward the Pacific Ocean over the past 500 years, they conquered a number of non-

Both the czars and the USSR had a policy of Russification, whereby large numbers of ethnic Russian migrants were settled in non-

Russification the czarist and Soviet policy of encouraging ethnic Russians to settle in non-

The Conflict in Chechnya Shortly after the breakup of the Soviet Union, several internal republics demanded more autonomy, and two of them, Tatarstan and Chechnya, declared outright independence. Tatarstan has since been placated with greater economic and political autonomy. However, Chechnya’s stronger resistance to Moscow’s authority has led to the worst bloodshed of the post-

Chechnya, located on the fertile northern flanks of the Caucasus Mountains (see the inset map in Figure 5.17), is home to 800,000 people. Partially in response to Russian oppression, the Chechens converted from Orthodox Christianity to the Sunni branch of Islam in the 1700s. Since then, Islam has served as an important symbol of Chechen identity and as an emblem of resistance to the Orthodox Christian Russians, who annexed Chechnya in the nineteenth century.

In 1942, during World War II, as the Germans invaded Russia, a group of Chechens rebels simultaneously waged a guerilla war against the Soviets. Near the end of the war, Stalin exacted his revenge by deporting the majority of the Chechen population (as many as 500,000 people) to Kazakhstan and Siberia. Here they were held in concentration camps, and many died of starvation. The Chechens were finally allowed to return to their villages in 1957, but a heavy propaganda campaign portrayed them as traitors to Russia, a designation that greatly affected their daily lives.

In 1991, as the Soviet Union was dissolving, Chechnya declared itself an independent state. Russia saw this as a dangerous precedent that could spark similar demands by other cultural enclaves throughout its territory. Russia also wished to retain the agricultural and oil resources of the Caucasus; it had planned to build pipelines across Chechnya to move oil and gas to Europe from Central Asia. Russia responded to acts of terrorism by Chechen guerrillas with bombing raids and other military operations that killed tens of thousands of people and created 250,000 refugees.

Most Chechen guerillas have since given up, most Russian combat troops have been pulled out of Chechnya, and Russia has begun making substantial investments in rebuilding the capital city of Grozny. While this shift is a welcome change, some Chechen rebels have continued their struggle by carrying out brutal terrorist attacks, many of which now take place in Moscow and other areas outside Chechnya. Chechnya remains highly militarized (see Figure 5.16C), and the ongoing conflict there continues to raise doubts about Russia’s ability to peacefully address internal political dissent.  116. CHECHNYA HANGS ON TO UNEASY PEACE

116. CHECHNYA HANGS ON TO UNEASY PEACE

Conflict in Georgia Just south of Chechnya, conflicts between Russia and Georgia over the ethnic republics of South Ossetia and Abkhazia have worsened in the post-

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

Controlling Nuclear Material

In the post–

In 2008, Georgia’s military, attempting to gain control over rebelling parts of South Ossetia, engaged with the Russian army on Russian territory, but that conflict ended without clear resolution. It is not clear at this time whether Abkhazia and South Ossetia will break away and become independent countries, become provinces within the Russian Federation, or be satisfied by offers of more autonomy within Georgia’s federal structure.

The Media and Political Reform During the Soviet era, all communication media were under government control. There was no free press, and public criticism of the government was a punishable offense. Between 1991 and the early 2000s, the communications industry was a center of privatization, and several media tycoons emerged to challenge the authorities. Privately owned newspapers and television stations regularly criticized the policies of various leaders of Russia and the other states. It appeared that a free press was developing.

In Vladimir Putin’s rise to power, however, the most outspoken newspapers and TV stations in Russia were shut down. Since then, critical analysis of the government has become rare throughout Russia. Journalists openly critical of government policies have been treated to various forms of punishment: censorship, exile, or violence. Since 2000, about 200 journalists have been killed under suspicious circumstances.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

GEOGRAPHIC INSIGHT 3

Power and Politics This region has a long history of authoritarianism. While there is some pressure to expand political freedoms, there are still few opportunities for the public to influence the political process. Elected representative bodies often act as rubber stamps for very strong presidents and exercise only limited influence on policy making.

A series of so-

called color revolutions took place throughout this region, led by coalitions of educated young adults, and funded largely by foreign NGOs and governments, including that of the United States, that wanted to hasten democratization. In early 2014, one of the most challenging crises this region has seen since the fall of the Soviet Union emerged in Ukraine, pitting Russia against the EU and the United States, in a seeming throwback to the days of the Cold War.

Russia’s long history of expansion into neighboring lands has left it and surrounding countries with exceptionally complex internal political geographies.