7.2 PHYSICAL GEOGRAPHY AND ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES

PHYSICAL PATTERNS

The African continent is big—

Landforms

The surface of the continent of Africa can be envisioned as a raised platform, or plateau, bordered by fairly narrow and uniform coastal lowlands. The platform slopes downward to the north; it has an upland region with several high peaks in the southeast, and lower uplands in the northwest. The steep escarpments (long, high cliffs) between plateau and coast have obstructed transportation and hindered connections to the outside world. Africa’s lengthy, uniform coastlines provide few natural harbors; Cape Town in South Africa being an exception (see Figure 7.1E).

Geologists usually place Africa at the center of the ancient supercontinent Pangaea (see Figure 1.8). As landmasses broke off from Africa and moved away—

Africa continues to break apart along its eastern flank. There, the Arabian Plate has already split away and drifted to the northeast, leaving the Red Sea, which separates Africa and Asia. Another split, known as the Great Rift Valley, extends south from the Red Sea more than 2000 miles (3200 kilometers) (see Figure 7.1C). In the future, Africa is expected to split again along these rifts.

Climate and Vegetation

Most of sub-

Most rainfall comes to Africa by way of the intertropical convergence zone (ITCZ), a band of atmospheric currents that circle the globe roughly around the equator (see the inset map in Figure 7.5). At the ITCZ, warm winds converge from both the north and the south and push against each other. This causes the air to rise, cool, and release moisture in the form of rain. The rainfall produced by the ITCZ is most abundant in Africa near the equator, where dense tropical rainforests flourish in places such as the Congo Basin (see Figure 7.5A, D).

intertropical convergence zone (ITCZ) a band of atmospheric currents that circle the globe roughly at the equator; warm winds from both north and south converge at the ITCZ, pushing air upward and causing copious rainfall

The ITCZ shifts north and south seasonally, generally following the area of Earth’s surface that has the highest average temperature at any given time. Thus, during the height of summer in the Southern Hemisphere in January, the ITCZ might bring rain far enough south to water the dry grasslands, or steppes, of Botswana. During the height of summer in the Northern Hemisphere in August, the ITCZ brings rain as far north as the southern fringes of the Sahara, to the area called the Sahel, a band of arid grassland 200 to 400 miles (320 to 640 kilometers) wide that runs east-

The tropical wet climates that support equatorial rain forests are bordered on the north, east, and south by seasonally wet/dry subtropical woodlands (see Figure 7.5B). These give way to moist tropical savannas or steppes, where tall grasses and trees intermingle in a semiarid environment. These tropical wet, wet/dry, and steppe climates have provided suitable land for different types of agriculture for thousands of years, but the amount of moisture available in each of these climates can vary greatly, in cycles that are decades long. Farther to the north and south lie the true desert zones of the Sahara, the Namib, and the Kalahari (see Figure 7.5C). This banded pattern of African ecosystems is modified in many areas by elevation and wind patterns.

Without mountain ranges to block them, wind patterns can have a strong effect on climate in Africa. Winds blowing north along the east coast keep ITCZ-

Horn of Africa the triangular peninsula that juts out from northeastern Africa below the Red Sea and wraps around the Arabian Peninsula

7.2.1 ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES

GEOGRAPHIC INSIGHT 1

Environment: Sub- 158. DISAPPEARING GLACIERS ON MT. KILIMANJARO RAISE ENVIRONMENTAL CONCERNS

158. DISAPPEARING GLACIERS ON MT. KILIMANJARO RAISE ENVIRONMENTAL CONCERNS

Deforestation and Climate Change

Sub-

carbon sequestration the removal and storage of carbon taken from the atmosphere

African countries lead the world in the rate of deforestation, the percentage of total forest area lost. Of the eight countries that had the world’s highest rates of deforestation between 1990 and 2005, six are in sub- 168. PLAN TO CLEAR-CUT UGANDAN FOREST RESERVE FOR GROWING SUGARCANE SPARKS CONTROVERSY

168. PLAN TO CLEAR-CUT UGANDAN FOREST RESERVE FOR GROWING SUGARCANE SPARKS CONTROVERSY

THINKING GEOGRAPHICALLY

Use the Photo Essay above to answer these questions.

Question 7.1

A Other than the caption, what clues are there to suggest that this landscape has been cleared of forest?

Question 7.2

B What about this photo suggests that the trees being logged are from old-

Question 7.3

C What about the fishing method depicted in the photo suggests that catches are fairly small in size?

VIGNETTE

Liberian environmental activist Silas Siakor is an affable and unassuming fellow. But his casual style belies his remarkable sleuthing ability and fierce dedication to his homeland. At great personal risk, Siakor uncovered evidence that 17 international logging companies were bribing Liberia’s then-

Silas Siakor pulled together publicly available information that had been previously ignored by the international community and information provided by ordinary citizens in ports, villages, and lumber companies. He prepared a clear, well-

In Liberia, democratic elections followed in 2006, after which Ellen Johnson-

The story of Silas Siakor and Ellen Johnson-

Most of Africa’s deforestation is driven by the growing demand for farmland and fuelwood, although logging by international timber companies is also increasing. Africans use wood (or charcoal made from wood) to supply nearly all their domestic energy (see Figure 7.6A, B). Wood remains the cheapest fuel available, in part because of African traditions that consider forests to be a free resource held in common. Even in Nigeria, a major oil producer, most people use fuelwood because they cannot afford petroleum products. Not only are charcoal prices rising across the region as the forests disappear, but the smoke from the charcoal is causing asthma and other respiratory problems, as well as creating greenhouse gases.

In Maputo, the capital of Mozambique, a group of small-

The multifaceted stove/ethanol/cassava pilot project in Maputo is funded by four American firms that hope to replicate it elsewhere around the world. Their goal is to save the forests, relieve fuel shortages, halt rising fuelwood prices, and alleviate air pollution. Other benefits include improving food security, since cassava is a major food crop in Africa, and creating local small businesses that can convert cassava into ethanol and build the innovative cookstoves.

Elsewhere, African governments that are trying to slow deforestation are encouraging agroforestry—the farming of economically useful trees in conjunction with the usual subsistence and cash crops. Using the farmed trees for fuel and construction helps reduce dependence on old-

agroforestry growing economically useful crops of trees on farms, in conjunction with the usual plants and crops, to reduce dependence on trees from nonfarmed forests and to provide income to the farmer

Agricultural Systems, Food, Water, and Vulnerability to Climate Change

Agricultural systems in Africa are undergoing a rapid transition from subsistence farming to commercial farming. Unfortunately, this change is happening at a time when the advantages of traditional agriculture are just beginning to be appreciated. The social and environmental effects of turning rapidly to commercial production are not fully understood at this point, especially given the as-

Traditional Agriculture Most sub-

subsistence agriculture farming that provides food for only the farmer’s family and is usually done on small farms

mixed agriculture farming that involves raising a diverse array of crops and animals on a single farm, often to take advantage of several environmental riches

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

The Value of Agroforestry

Agroforestry has long been promoted by the Green Belt Movement, founded by Dr. Wangari Maathai of Kenya, which helps rural women plant trees for use as fuelwood and to reduce soil erosion. The movement grew from Maathai’s belief that a healthy environment is essential for democracy to flourish. Thirty years and 30 million trees after she began, Maathai was awarded the 2004 Nobel Peace Prize for her contributions to sustainable development, democracy, and peace.

To maintain soil quality in a tropical wet or wet/dry climate, subsistence farmers have for generations used shifting cultivation, in which small patches of forest are cleared, with the detritus either burned or left to decay. The clearings are cultivated with a wide variety of plants for 2 or 3 years and then are abandoned and left to regrow. After a few decades, the soil naturally replenishes its organic matter and nutrients and is ready to be cultivated again. However, when fallow periods are reduced, as is happening in many rural areas that have increasingly high population densities, the soil can become degraded.

shifting cultivation a productive system of agriculture in which small plots are cleared in forestlands, the dried brush is burned to release nutrients, and the clearings are planted with multiple species; each plot is used for only 2 or 3 years and then abandoned for many years of regrowth

These traditional, subsistence, mixed, and shifting cultivation food-

However, the subsistence nature of most African farming can also leave families without much cash. If harvests are too low to provide surplus that can be sold, and hunting and gathering fail to provide supplementary food for the family, there may not be enough money to buy food. While such situations can lead to famine, it is important to note that the most serious famines in Africa have occurred not because of low harvests but rather because of political instability that disrupts economies and food growing and distribution systems.  162. FELLOWSHIP PROGRAM AIMS TO OPEN DOORS FOR AFRICAN WOMEN IN AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH

162. FELLOWSHIP PROGRAM AIMS TO OPEN DOORS FOR AFRICAN WOMEN IN AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH

Commercial Agriculture Much of Africa is now shifting over to commercial agriculture, in which crops are grown deliberately for cash rather than solely as food for the farm family. This type of production also has advantages and disadvantages with respect to climate change. If harvests are good and prices for crops are adequate, farmers can earn enough cash to get them through a year or two of poor harvests. Having some cash income can also allow poor families to invest in other means of earning a living, such as opening a grinding mill to help process other farmers’ harvests or building a stone oven to bake neighbors’ bread for a fee.

commercial agriculture farming in which crops are grown deliberately for cash rather than solely as food for the farm family

However, some of the most common commercial crops, such as peanuts, cacao beans (used for making chocolate), rice, tea, and coffee, are often less adapted to environments outside their native range (Figure 7.8D). They are more likely to produce smaller yields if temperatures increase or water becomes scarce. Moreover, to maximize profits, these crops are often grown in large fields containing only a single plant species. This can leave crops vulnerable to pests; if crops fail, farmers have no other garden foods to rely on. The potential for commercial agriculture to help farmers adapt to the uncertainties of global climate change is also limited by the instability of prices for commercial crops. Prices can rise or fall dramatically from year to year because of overproduction or crop failures both in Africa and abroad.

THINKING GEOGRAPHICALLY

Use the Photo Essay above to answer these questions.

Question 7.4

A How is poverty evident in this photo?

Question 7.5

B What caused the death of many wildebeests in 2007?

Question 7.6

C How is agricultural diversity illustrated in this photo?

Question 7.7

D What kind of climate change in Africa most often causes a reduced yield for a crop like tea?

Commercial agriculture—

These aspects of commercial agricultural systems make them a risky choice even under the most ideal climatic conditions, let alone in the hotter and more drought-

Recently, agricultural scientists have begun to recognize past mistakes and have been trying to incorporate the traditional knowledge of African farmers, female and male, into commercial agriculture systems. For example, scientists at Nigeria’s International Institute for Tropical Agriculture are developing cultivation systems that, like traditional systems, use many species of plants that help each other cope with varying climatic conditions. Most of these systems are designed for both subsistence and commercial agriculture, and so can give families both a stable food supply and cash to help them ride out crop failures and pay school fees for their children (see Figure 7.8C).

Water Resources, Irrigation, and Water Management Alternatives Although sub-

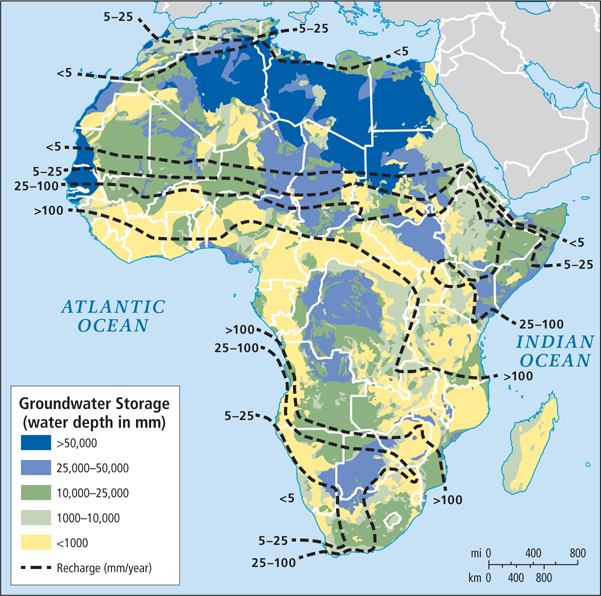

New Groundwater Discoveries Is there sufficient groundwater in Africa? Until recently, the answer was a resounding no. However, a recent comprehensive review and quantitative mapping of all available data on groundwater for the African continent (Figure 7.9) revealed that the quantity of groundwater (water naturally stored in aquifers as many as 5000 years ago, during wetter climate conditions) was nearly 100 times that of previous estimates. In many cases, the water was close enough to the surface to be accessed via inexpensive bore well pumps. This does not mean that Africa suddenly has an inexhaustible supply of water. Nor does it mean that it will be easy to get this water to the people who need it. The largest reservoirs of groundwater are in lightly populated areas (such as North Africa and Botswana; see Figure 7.1A). The most heavily populated country, Nigeria, has only a relatively small supply of groundwater. Nonetheless, this news on groundwater resources is welcome because climate change is likely to reduce precipitation in irregular and unpredictable patterns across the continent, and because per capita water use is likely to expand exponentially as this region develops economically (see Chapter 1).

groundwater water naturally stored in aquifers as many as 5000 years ago during wetter climate conditions

New Large-

The Niger rises in the tropical wet Guinea Highlands and carries summer floodwaters northeast into the normally arid lowlands of Mali and Niger (see the Figure 7.5 map and Figure 7.6C, D). There the waters spread out into lakes and streams that nourish wetlands. For a few months of the year (June through September), the wetlands ensure the livelihoods of millions of fishers, farmers, and pastoralists. These people share the territory in carefully synchronized patterns of land use that have survived for millennia. Wetlands along the Niger produce 8 times more plant matter per acre than the average wheat field does. They provide seasonal pasture for millions of domesticated animals, and serve as an important habitat for wildlife.

The governments of Mali and Niger now want to dam the Niger River and channel its water into irrigated agribusiness projects that they hope will help feed the more than 26 million people in both countries. However, the dams would forever change the seasonal rise and fall of the river. The irrigation systems may also pose a threat to human health. Systems that rely on surface storage not only lose a great deal of water through evaporation and leakage, but the standing pools of water they create often breed mosquitoes that spread tropical diseases such as malaria, and harbor the snails that host schistosomiasis, a debilitating parasite that enters the skin of humans who spend time standing in still water to fish or do other chores.

Many smaller-

Herding and Desertification Herding, or pastoralism, is practiced by millions of Africans, primarily in savannas, on desert margins, and in the mixture of grass and shrubs called open bush. Herders live off the milk, meat, and hides of their animals. They typically circulate seasonally through wide areas, taking their animals to available pasturelands and trading with settled farmers for grain, vegetables, and other necessities.

pastoralism a way of life based on herding; practiced primarily on savannas, on desert margins, and in the mixture of grass and shrubs called open bush

Many traditional herding areas in Africa are now undergoing desertification, the process by which arid conditions spread to areas that were previously moist (see Chapter 6). This drying out is often the result of the loss of native vegetation; traditional herding may be partially to blame, but economic development schemes that encourage cattle raising are also at fault. Cattle need more water and forage than do traditional herding animals and therefore place greater stress on native grasslands than goats or camels do. Agricultural intensification in the Sahel also contributes to desertification, as scarce water resources are diverted to irrigation, leaving dry, vegetation-

Over the last century, desertification has shifted the Sahel to the south. For example, the World Geographic Atlas in 1953 showed Lake Chad situated in a forest well south of the southern edge of the Sahel. By 1998, the Sahara itself was encroaching on Lake Chad (see the Figure 7.5 map) and the lake had shrunk to a tenth of the area it occupied in 1953.

Wildlife and Climate Change

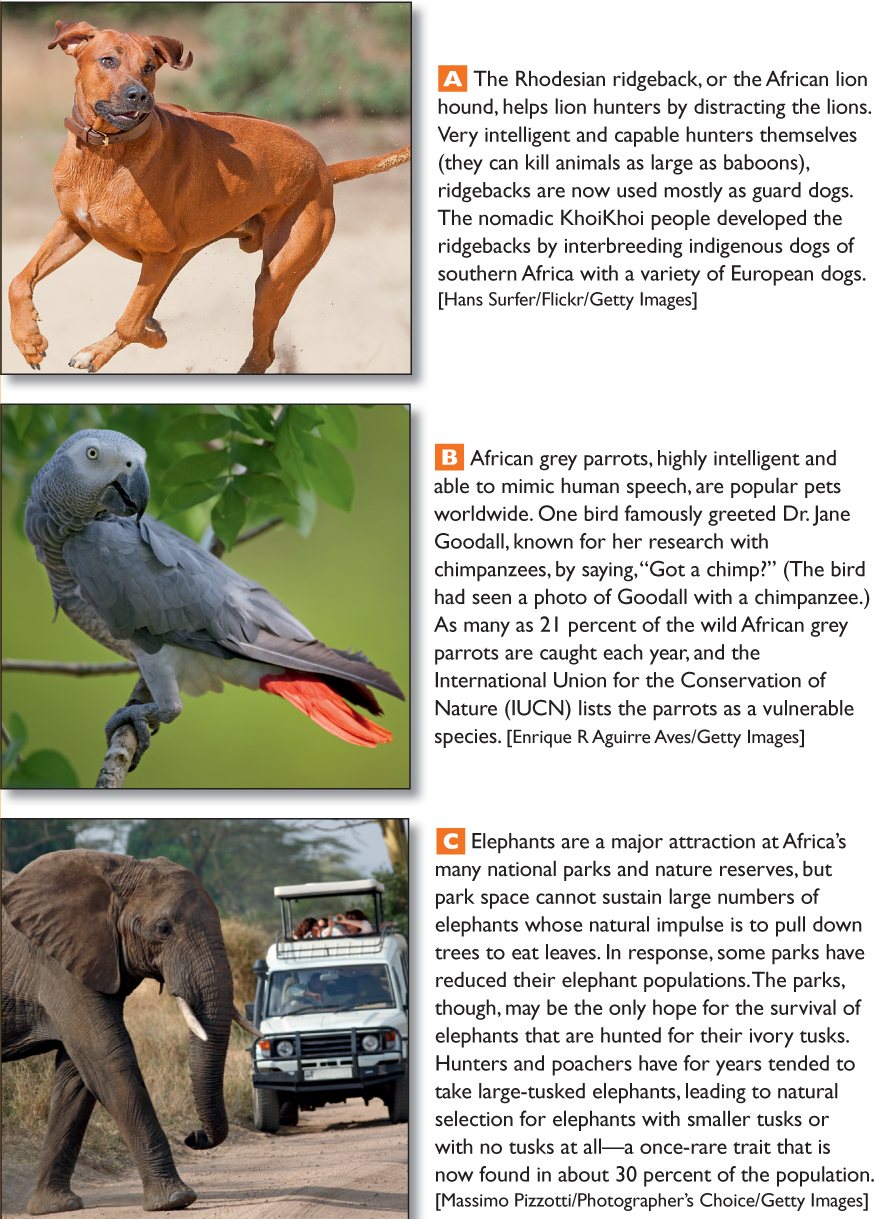

Africa’s world-

Wildlife managers are developing new management techniques to help animals survive. For example, one of the greatest wildlife spectacles on the planet took a tragic turn in 2007. The annual 1800- 169. PROTECTING NATURE IN GUINEA COLLIDES WITH HUMAN NEEDS

169. PROTECTING NATURE IN GUINEA COLLIDES WITH HUMAN NEEDS

Farmers’ dependence on hunting wild game (bushmeat) for part of their food and income is already a major threat to wildlife in much of Africa. For example, farmers who need food or extra income are killing endangered species such as gorillas, chimpanzees, and especially elephants in record numbers (Figure 7.10C). If crop harvests are diminished by global climate change, many farmers will become even more dependent on bushmeat and on income from selling contraband, such as ivory. The threat to wild populations of various species has led to calls to expand and establish new protected areas for wildlife.

Africa’s national parks constitute one-

Some parks are now using profits from ecotourism to fund development in nearby communities that previously depended in part on poaching. For example, in 1985, wildlife poaching threatened the animal population in Zambia’s Kasanka National Park. Park managers decided to generate employment for the villagers through tourism-

THINGS TO REMEMBER

The surface of the continent of Africa can be envisioned as a raised platform, or plateau, bordered by fairly narrow and uniform coastal lowlands.

Most of sub-

Saharan Africa has a tropical wet or wet/dry climate, except at the southern tip and in the cooler uplands. Seasonal climates in Africa differ more by the amount of rainfall than by temperature. Most rainfall comes to Africa by way of the intertropical convergence zone (ITCZ), a band of atmospheric currents that circle the globe roughly around the equator. The effects of desertification are most dramatic in the region called the Sahel.

GEOGRAPHIC INSIGHT 3

Environment Sub-

Saharan Africa’s poverty and political instability leave its people less able to adapt to climate change than the inhabitants of other world regions, though many Africans are developing strategies to cope with increasing variability in rainfall and temperature. As a whole, this region has contributed little to the build- up of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, but deforestation by rural Africans and by multinational logging companies is intensifying global climate change. The primary way in which sub-

Saharan Africa contributes to CO2 emissions and potential climate change is through deforestation. Much of Africa’s deforestation is driven by the growing demand for farmland and fuelwood, but corruption on the part of local authorities and international timber companies also plays a role. Long-

standing physical challenges, such as deforestation, desertification, and increasing water scarcity, have had a major impact on sub- Saharan Africa’s ecosystems. Commercial food production for Africa’s cities has many ecological drawbacks. These challenges are likely to increase with climate change. Newly discovered groundwater resources hold promise for alleviating some of Africa’s water scarcities.