7.5 POWER AND POLITICS

GEOGRAPHIC INSIGHT 3

Power and Politics: Governments in sub-

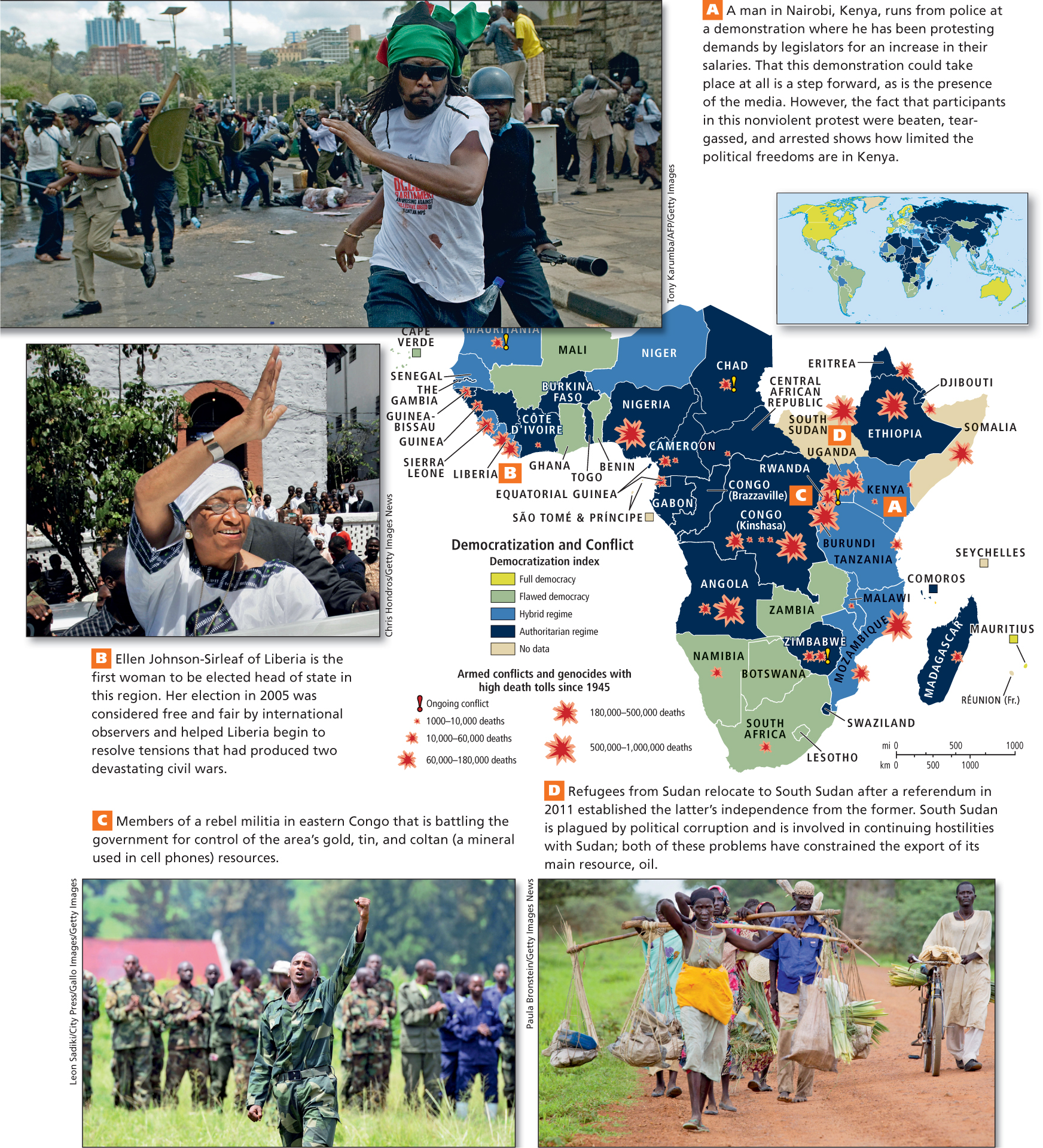

After years of being ruled by corrupt elites and the military, Africa is now shifting toward systems with greater political freedoms. Yet change is often blocked by conflict, and even when reforms are enacted and free elections established, violence often accompanies these elections.

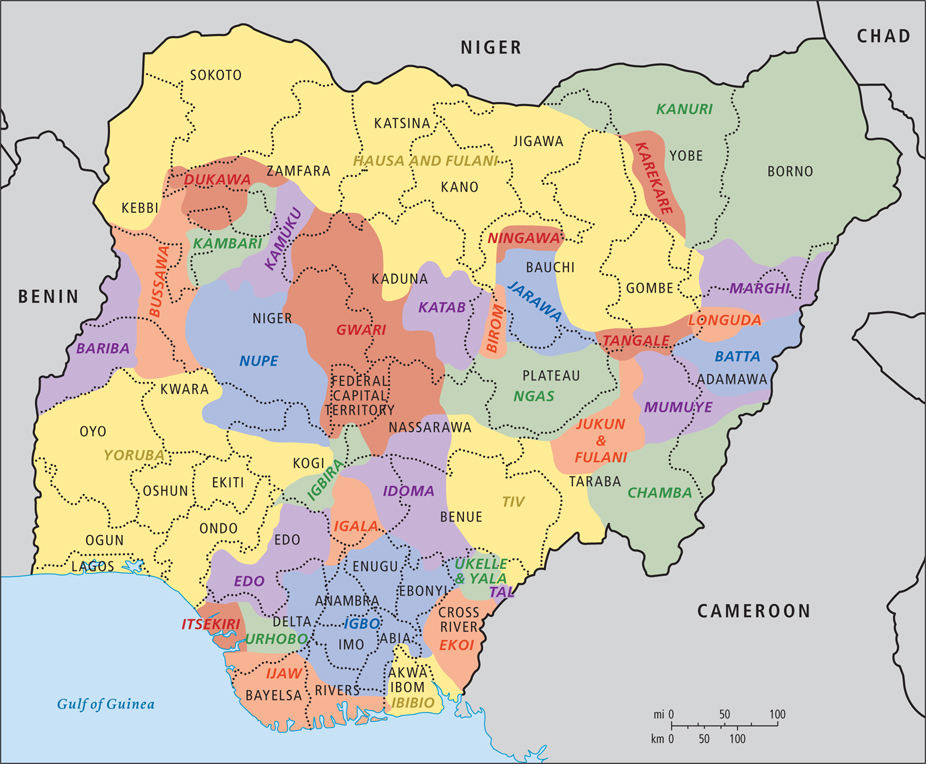

Ethnic Rivalry Africa has suffered from frequent civil wars that are in many ways the legacy of colonial era policies of divide and rule. Divisions and conflicts between ethnic or religious groups were deliberately aggravated by European colonial powers. To make it difficult for Africans to unite against colonial rule, the borders and administrative units of the African colonies were designed so that different and sometimes hostile groups were put together under the same jurisdiction (Figure 7.20 shows the situation in Nigeria).

divide and rule the deliberate intensification of divisions and conflicts by potential rulers; in the case of sub-

After independence, when Africans took over, governance was complicated because African officials inevitably belonged to one local ethnic group or another and so were not seen as impartial in their attempts to resolve conflicts. Moreover, during the colonial era, older indigenous traditions for ensuring ethical behavior, punishing greed by leaders, and resolving ethnic conflict had been weakened. The political institutions that replaced them were often not adept at conflict resolution, resulting in hostilities between ethnic groups that have at times devolved into civil wars (Figure 7.21C).

THINKING GEOGRAPHICALLY

Use the Photo Essay above to answer these questions.

Question 7.16

A In what ways does this picture show both the strengths and limits of political freedoms in Kenya?

Question 7.17

B Why might it be significant that Ellen Johnson-

Question 7.18

C What does this photo suggest about the strength of this rebel militia and its ability to acquire uniforms and arms?

Question 7.19

D What does this photo convey about the general well-

CASE STUDY

Conflict in Nigeria

Nigeria was and remains in part a creation of British divide-

The British reinforced a north-

The politics of oil have complicated the troubles in Nigeria. Nigeria’s oil is located on lands occupied by the Ogoni people, which lie in the south along the edges of the Niger River delta (see Figure 7.1D). The Ogoni are a group of about 300,000 who are distinct from other ethnicities in Nigeria. Virtually none of the profits from oil production and export and very little of the oil itself goes to Ogoniland. While receiving few benefits from oil extraction, Ogoniland has suffered gravely from the resulting pollution (see the photo in Figure 1.4). Oil pipelines crisscross Ogoniland, and spills and blowouts are frequent; between 1985 and 2009 there were hundreds of spills, many larger than that of the Exxon Valdez disaster in Alaska. Natural gas, a by-

Geographic strategies have been used to reduce tensions in Nigeria. One approach has been to create more political states (Nigeria now has 30) and thereby reallocate power to smaller local units with fewer ethnic and religious divisions. However, when large, wealthy states were subdivided, reputedly to spread oil profits more evenly, the actual effect of the subdivision was to mute the voice and power of the public.

The Role of Geopolitics Cold War geopolitics between the United States and the former Soviet Union deepened and prolonged African conflicts that grew out of divide-

In the 1970s and 1980s, southern sub-

Conflict and the Problem of Refugees Conflicts create refugees and refugees are commonplace across sub-

genocide the deliberate destruction of an ethnic, racial, religious, or political group

As difficult as life is for these refugees, they also place a severe burden on the areas that host them. Even with help from international agencies, the host areas find their own development plans deferred by the arrival of so many distressed people who must be fed, sheltered, and given health care. Large portions of economic aid to Africa have been diverted to deal with the emergency needs of refugees.

Successes and Failures of Democratization In sub-

While the implementation of democratic elections has increased (see Figure 7.21B), the growth of other political freedoms—

At times, flawed elections have brought about massive violence. In 2008, after several peaceful election cycles, Kenya had an election so corrupt that the country erupted in deadly protest riots. More than 1000 people died and 600,000 were displaced by mobs of enraged voters. By 2010, a new Kenyan constitution gave some hope that political freedoms would be better protected. In 2008, local elections in Nigeria sparked similar violence, and in the Congo (Kinshasa) in 2006, the first elections held there in 46 years resulted in violence that left more than 1 million Congolese people refugees within their own country. In the 2012 parliamentary elections, the will of the voting public became more evident when the ruling party lost more than 40 percent of its legislative seats to opposition parties.

Zimbabwe may represent the worst case of the failed attempts at democratization. In the 1970s, Robert Mugabe became a hero to many for his successful guerilla campaign in what was then called Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). The defeated white minority government had been allied with apartheid South Africa but was not formally recognized by any other country because of its extreme racist policies. Mugabe was elected president in 1980, following relatively free multiparty elections. Over the years, however, his authoritarian policies have impoverished and alienated more and more Zimbabweans while increasing his personal wealth. In the 1990s, he implemented a highly controversial land- 159. ZIMBABWE’S ROBERT MUGABE—A PROFILE

159. ZIMBABWE’S ROBERT MUGABE—A PROFILE

In other places, however (most recently in South Sudan and Rwanda and some years ago in South Africa), elections have helped end civil wars and resettle refugees as the possibility of becoming respected elected leaders induced former combatants to lay down their arms. In Sierra Leone and Liberia, public outrage against corrupt ruling elites resulted in elections that brought fortuitous changes of leadership. Over the long term, fair and regular elections can help enable people to have more input at the policy level, which forces governments to be more responsive to the needs of their citizens.

Gender, Power, and Politics

The education of African women and their economic and political empowerment are now recognized as essential to development. As girls’ education levels rise, population growth rates fall; as the number of female political leaders increases, so does their influence on policies designed to reduce poverty.

One major characteristic of the expansion of political freedoms has been the increase in the number of women across Africa who are assuming positions of political influence. This chapter opened with the story of Juliana Rotich, a businesswoman in Kenya whose road to success was built on policy changes pushed by a number of female Kenyan political figures over the last decade. In Nigeria, Ngozi Okonjo- 170. WOMEN HAVE STRONG VOICE IN RWANDAN PARLIAMENT

170. WOMEN HAVE STRONG VOICE IN RWANDAN PARLIAMENT

There has been a sea change in attitudes toward women in politics. The policies that establish quotas for the number of female members of parliament are usually a reflection of a larger, post-

THINGS TO REMEMBER

GEOGRAPHIC INSIGHT 3

Power and Politics Governments in sub-

Saharan Africa tend to be authoritarian, though there is a general shift in the region toward the expansion of political freedoms. Free and fair elections have brought about dramatic changes in some countries, while elections tainted by widespread suspicions of fraud have often been followed by surges of violence in other countries. Africa has suffered from frequent civil wars that are in many ways the legacy of colonial era policies of divide and rule.

With only 11 percent of the world’s population, this region contains about 19 percent of the world’s refugees, and if people displaced within their home countries are also counted, the region has about 28 percent of the world’s refugee population.

Over the long term, fair and regular elections can help enable people to have more input at the policy level, which forces governments to be more responsive to the needs of their citizens.

One major characteristic of the expansion of political freedoms has been the increase in the number of women across Africa who are coming into positions of political power. 3