8.2 PHYSICAL GEOGRAPHY AND ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES

PHYSICAL PATTERNS

Many of the landforms and even climates of South Asia are the result of huge tectonic forces. These forces have positioned the Indian subcontinent along the southern edge of the Eurasian continent, where it is surrounded by the warm Indian Ocean and shielded from cold airflows from the north by the massive mountains of the Himalayas (see Figure 8.1).

Landforms

The Indian subcontinent and the territory surrounding it are a dramatic illustration of what can happen when two tectonic plates collide. The Indian-

The three great rivers of South Asia—

Lying south of the Indo-

Because of its continual high degree of tectonic activity and deep crustal fractures, South Asia is prone to devastating earthquakes, such as the magnitude 7.7 quake that shook the state of Gujarat in western India in 2001; the 7.6 quake that hit the India–

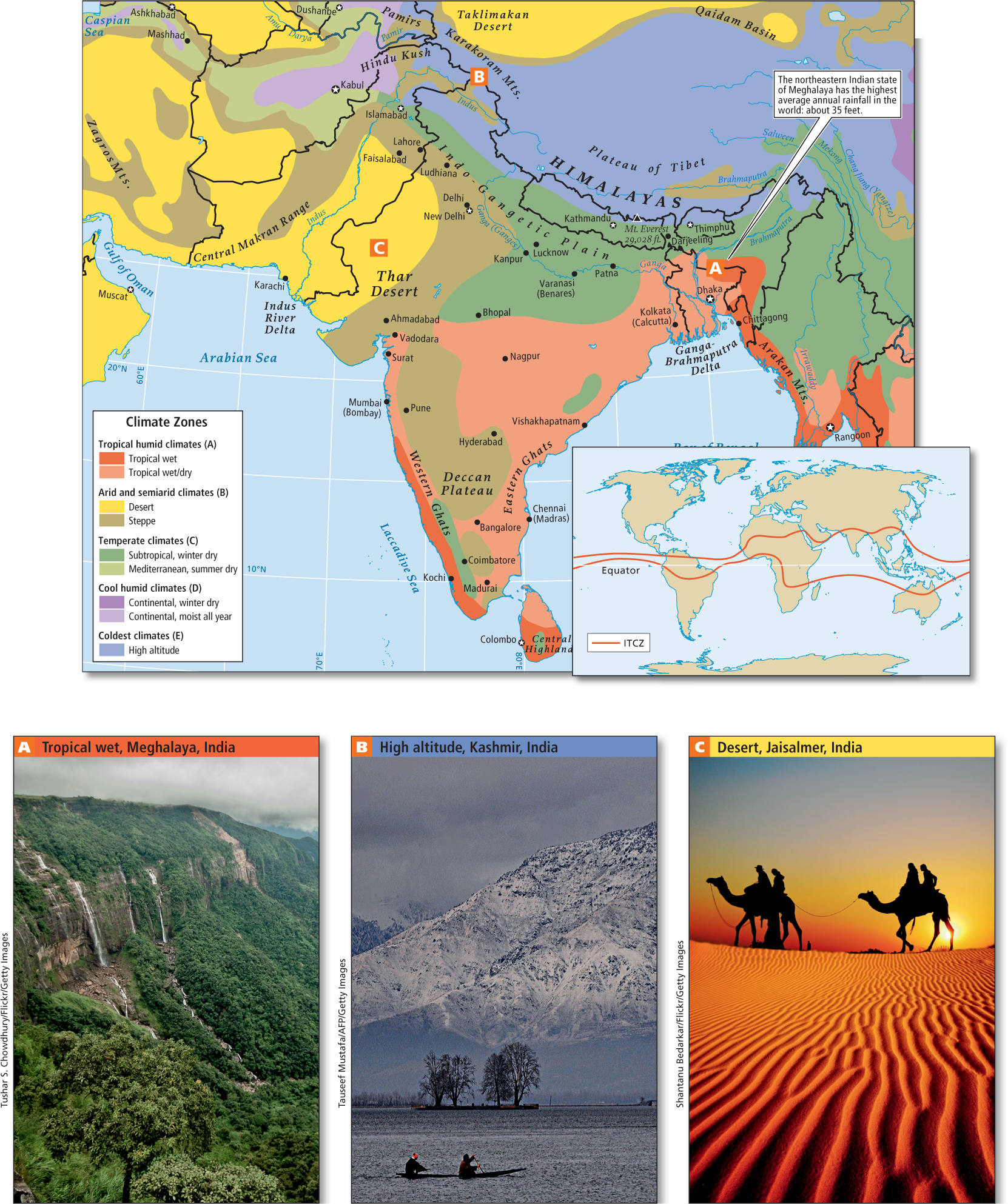

Climate and Vegetation

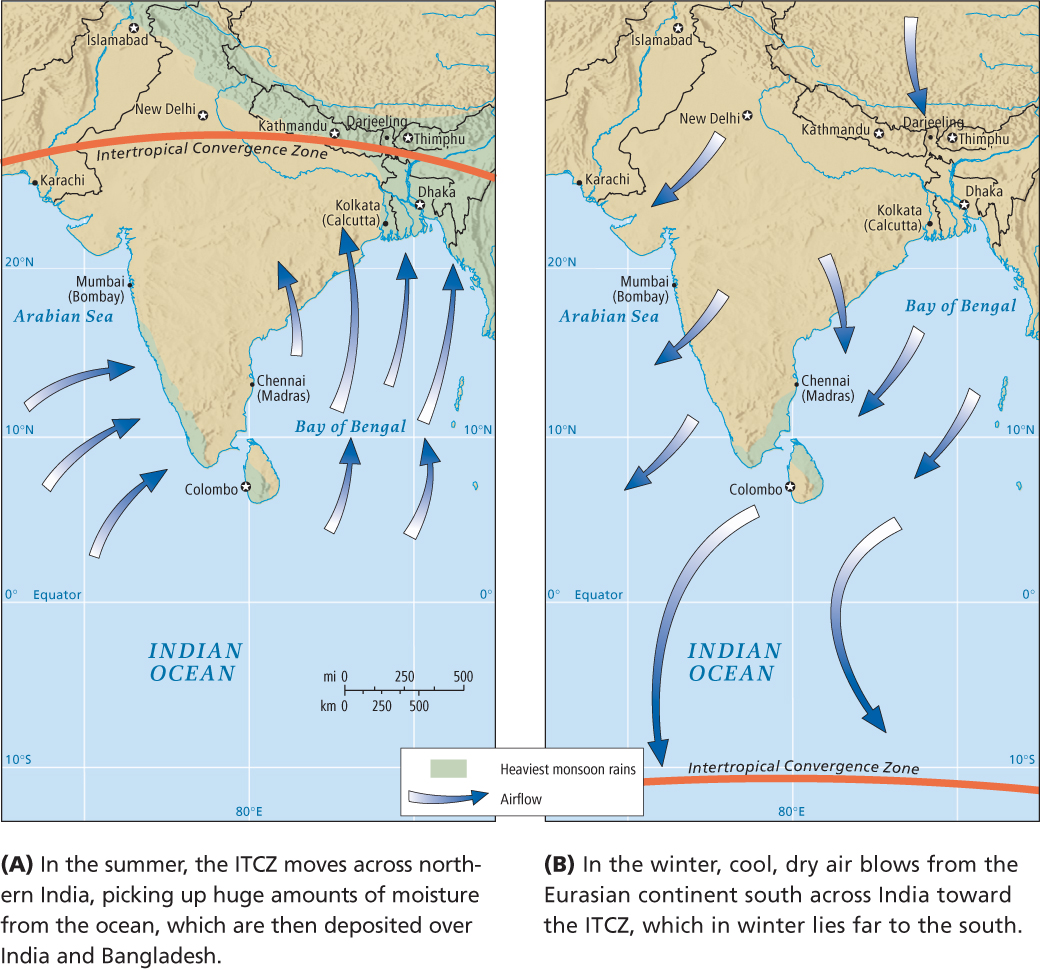

The climate of South Asia is characterized by a seasonal reversal of winds known as monsoons (Figure 8.4). These monsoon winds are affected by the intertropical convergence zone (ITCZ), which, as the name suggests, is a zone created when air masses moving south from the Northern Hemisphere and north from the Southern Hemisphere converge near the equator. As the warm air rises and cools, it drops copious amounts of precipitation. As described in Chapter 7, the ITCZ shifts north and south seasonally. The intense rains of South Asia’s summer monsoons are likely caused by the ITCZ being sucked onto the land by a vacuum created when huge air masses over the Eurasian continent heat up and rise into the upper troposphere.

The summer monsoon (see Figure 8.4A) begins in early June, when the warm, moist ITCZ air first reaches the mountainous Western Ghats. The rising air mass cools as it moves over the mountains, releasing rain that nurtures patches of dense tropical rain forests and tropical crops on the upper slopes of the Western and Eastern Ghats and in the central uplands. Once on the other side of India, the monsoon gathers additional moisture and power in its northward sweep up the Bay of Bengal, sometimes turning into tropical cyclones.

summer monsoon rains that begin every June when the warm, moist ITCZ air first reaches the mountainous western Ghats

As the monsoon system reaches the hot plains of Bangladesh and the Indian state of West Bengal in late June, columns of warm, rising air create massive, thunderous cumulonimbus clouds that drench the parched countryside. Monsoon rains sweep east to west, parallel to the Himalaya Mountains, moving across northern India to Pakistan and finally petering out over the Kabul Valley in eastern Afghanistan by July. Rainfall is especially intense in the east, north of the Bay of Bengal, where the town of Darjeeling holds the world record for annual rainfall—

Periodically, the monsoon seasonal pattern is interrupted and serious drought ensues. This happened in July and August of 2009, when the worst drought in 40 years struck much of South Asia (see the discussion below). Then in September of 2009, heavy rains came to central south India, causing crop-

The winter monsoon (see Figure 8.4B) is underway by November each year, when the cooling Eurasian landmass sends the cooler, drier, heavier air over South Asia. This cool, dry air from the north sinks down to the lower elevations and pushes the warm, wet air back south to the Indian Ocean. Very little rain falls in most of the region during this winter monsoon. However, as the ITCZ retreats southward across the Bay of Bengal, it picks up moisture that is then released as early winter rains over parts of southeastern India and Sri Lanka.

winter monsoon a weather pattern that begins by November, when the cooling Eurasian landmass sends the cooler, drier, heavier air over South Asia

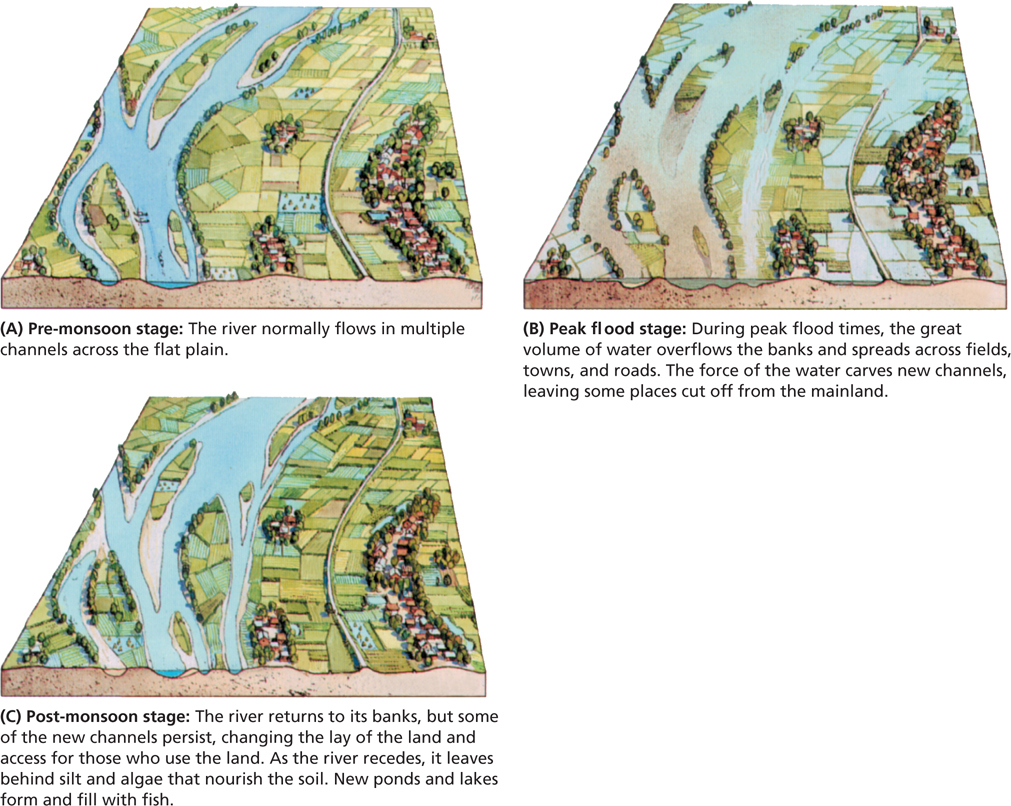

The monsoon rains deposit large amounts of moisture over the Himalayas, much of it in the form of snow and ice that add to the existing mass of glaciers (see Chapter 1). Meltwater from these glaciers feeds the headwaters of the Indus, the Ganga, and the Brahmaputra. These rivers carry enormous loads of sediment, especially during the rainy season. When the rivers reach the lowlands, their velocity slows and much of the sediment settles out as silt which is then repeatedly picked up and redeposited by successive floods. As illustrated in the diagram of the Brahmaputra River in Figure 8.6, the movement of silt constantly rearranges the floodplain landscape, complicating human settlement and agricultural efforts. However, the seasonal deposit of silt nourishes much of the agricultural production in the densely occupied plains of Bangladesh. The same is true on the Ganga and Indus plains.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Because of the high degree of tectonic activity and deep crustal fractures, all the countries of South Asia are prone to devastating earthquakes.

The three major rivers of this region originate from glacial meltwater high in the northwest Himalaya Mountains.

The monsoons have a major influence on South Asia’s climate. In June, the warm, moist air of the summer monsoon reaches India, where coastal mountains and rising hot air force the moist monsoon air up, cooling it and causing rain. Monsoon rains run parallel to the Himalayas in a variable band that reaches across northern India and Pakistan, finally petering out over the Kabul Valley in eastern Afghanistan by July.

Periodic interruptions of the monsoon rainfall patterns can result in devastating droughts.

Precipitation from monsoons is especially intense in the eastern foothills of the Himalayas.

The three main rivers—

the Indus, the Ganga, and the Brahmaputra— carry enormous loads of sediment and deposit it as silt, a process that is repeated by successive floods. The movement of silt constantly rearranges the floodplain landscape, complicating human settlement and agricultural efforts.