8.4 HUMAN GEOGRAPHY

Home to some of the earth’s oldest and most influential civilizations, South Asia faces the world’s great transitions with an enviable ability to innovate while maintaining ancient traditions. Tens of thousands of years of continuous human occupation, and the integration of numerous influences from outside the region, have given South Asia astounding cultural diversity to draw on in this time of change. In the current era of globalization, South Asia is integrating powerful global economic forces while struggling to achieve an economic transformation that benefits more than a privileged few. The politics of this region are also in transition; people are demanding more political freedom, challenging the authoritarian systems of the past. In this most densely populated of world regions, the demographic transition is underway as population growth slows while changing gender roles give women more freedom. Throughout these great transitions, the people of South Asia often manage to create a synthesis of tradition and innovation that smooths over the most jarring changes.

8.4.1 HUMAN PATTERNS OVER TIME

A variety of groups have migrated into South Asia, many of them as invaders who conquered peoples already there. Despite much blending over the millennia, the continued coexistence and interaction of many of these groups make South Asia both a richly diverse and an extremely contentious place.

The Indus Valley Civilization

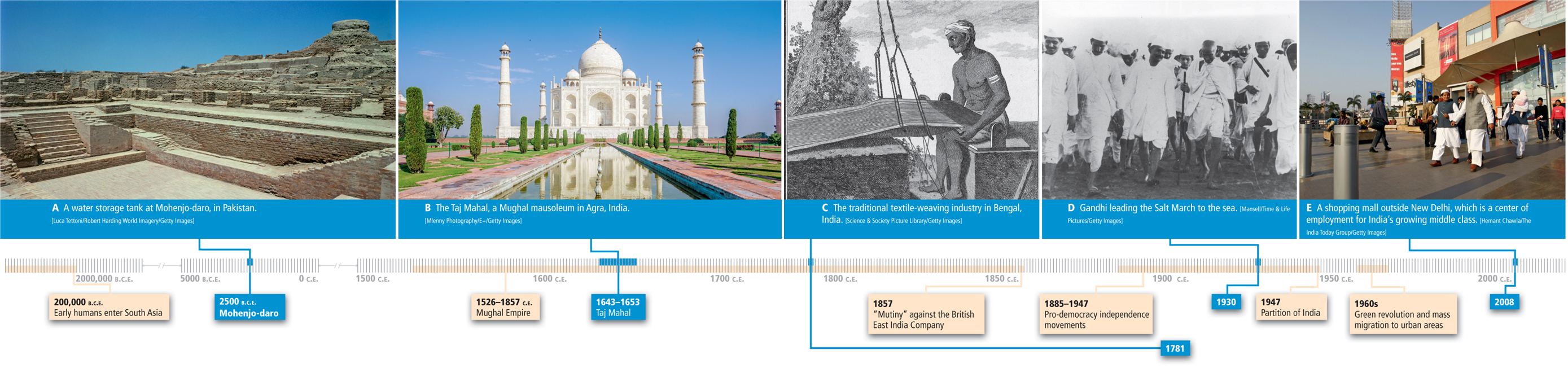

There are indications of early humans in South Asia as far back as 200,000 years ago, but the first real evidence of modern humans in the region is about 38,000 years old. The first large agricultural communities, known as the Indus Valley civilization (or Harappa culture), appeared about 4500 years ago along the Indus River in what is modern-

Indus Valley civilization the first substantial settled agricultural communities, which appeared about 4500 years ago along the Indus River in modern-

Harappa culture see Indus Valley civilization

Vestiges of the Indus Valley civilization’s agricultural system survive to this day in parts of the valley, including infrastructure for storing monsoon rainfall to be used for irrigation in dry times (shown in Figure 8.10A). Possible cultural and linguistic remnants of the Indus Valley civilization survive today among the Dravidian peoples of southern India, who originally migrated from the Indus region beginning about 2000 years ago.

THINKING GEOGRAPHICALLY

Use the Visual History above to answer these questions.

Scroll to see the full graphic.

Question 8.9

A This structure was designed to store water from what source?

Question 8.10

B Suggest some principal features of the structure and grounds of the Taj Mahal.

Question 8.11

C What is significant about the fact that as of 1750, before the onset of British colonialism, South Asia produced 12 to 14 times more cotton than Britain and the rest of Europe combined?

Question 8.12

D What was the immediate result of the Salt March?

Question 8.13

E What does this photo suggest about India’s modern economy?

Scholars have long debated the reasons for the decline of the Indus Valley civilization. Some believe that complex geologic (seismic) and ecological changes (drier climate) brought about a gradual demise. Others argue that foreign invaders brought a swift collapse, instigating out-

A Series of Invasions

The first recorded invaders to join the indigenous people of South Asia came from Central and Southwest Asia into the rich Indus Valley and Punjab about 3500 years ago. Many scholars believe that these people, referred to as Indo-

Wave after wave of other invaders arrived, including the Persians, the armies of the Greek general Alexander the Great, and numerous Turkic and Mongolian peoples. Defensive structures against these invaders can still be found across northwest South Asia. Jews came to the Malabar Coast of Southwest India more than 2500 years ago, Christians shortly after the time of Jesus. Arab traders came by land and sea to India long before the emergence of Islam; and then starting about 1000 years ago, Arab traders and religious mystics introduced Islam to what are now Afghanistan, Pakistan, and northwest India. By sea, the Arabs brought Islam to the coasts of southwestern India and Sri Lanka. In 1526, the Mughals, a group of Turkic Persian people from Central Asia, invaded from the north, intensifying the growth of Islam. The Mughals reached the height of their power and influence in the seventeenth century, controlling the north-

Mughals a dynasty of Central Asian origin that ruled India from the sixteenth century to the nineteenth century

Language and Ethnicity

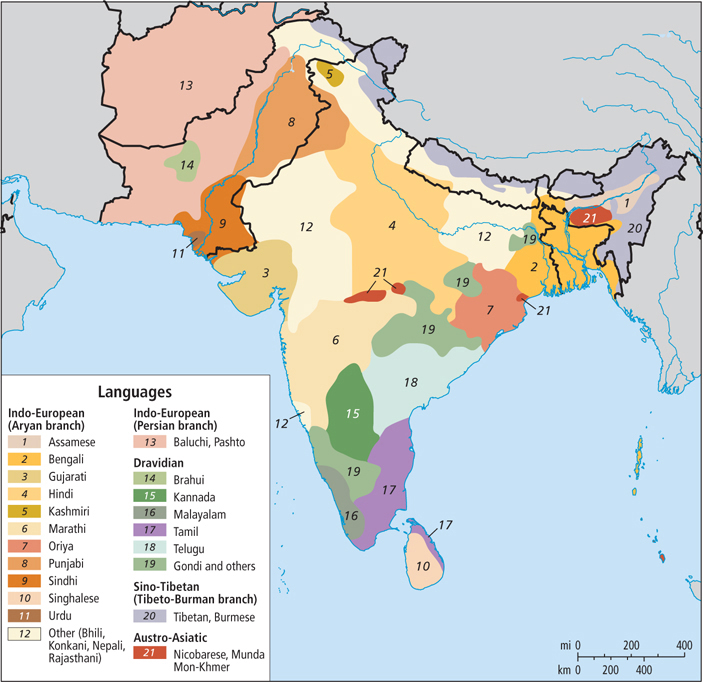

One result of the numerous invasions of South Asia over the millennia is that today there are many distinct ethnic groups, each with its own language or dialect. In India alone, 18 languages are officially recognized, but there are actually hundreds of distinct languages. This complexity results partly from strong cultural traditions that allow groups to maintain distinct identities in the midst of foreign cultures and withstand invasion or even factors that could force an entire group to relocate. As shown in Figure 8.11, the Dravidian language-

By the seventeenth century, Hindi—

Religious Traditions

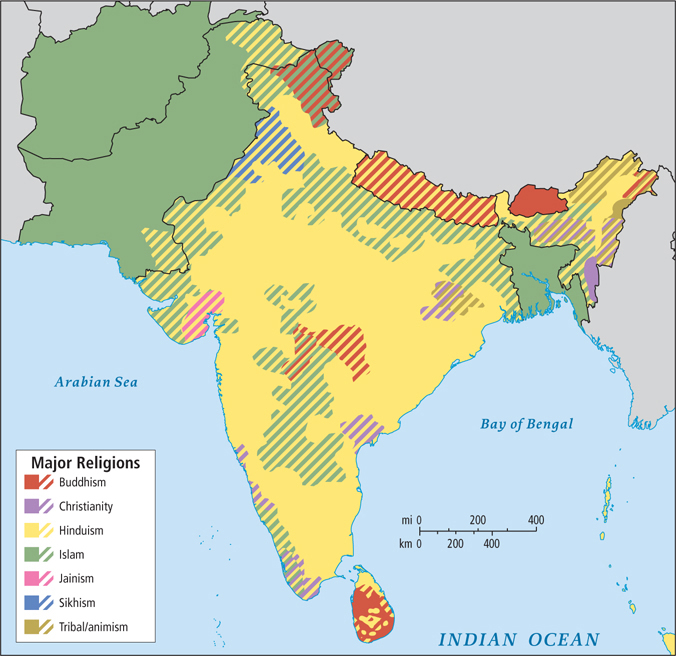

The main religious traditions of South Asia are Hinduism, Buddhism, Sikhism, Jainism, Islam, and Christianity (Figure 8.12). (For a discussion of Islam, Christianity, and Judaism, see Chapter 6.)

Hinduism is a major world religion practiced by approximately 900 million people, 800 million of whom live in India. It is a complex belief system, with roots in both ancient literary texts (known as the Great Tradition) and in highly localized folk traditions (known as the Little Tradition).

Hinduism a major world religion practiced by approximately 900 million people, 800 million of whom live in India; a complex belief system, with roots both in ancient literary texts (known as the Great Tradition)

The Great Tradition is based on 4000-

Some beliefs are held in common by nearly all Hindus. One is the belief in reincarnation, the idea that any living thing that desires the illusory pleasures (and pains) of life will be reborn after it dies. A reverence for cows, which are seen as only slightly less spiritually advanced than humans, also binds all Hindus together (see Figure 8.9B). This attitude, along with the Hindu prohibition on eating beef, may stem from the fact that cattle have been tremendously valuable in rural economies as the primary source of transport, field labor, dairy products, fertilizer, and fuel (animal dung is often burned).

Caste: An Explanation Hinduism includes the caste system, a complex and ancient way of dividing society into hereditary hierarchical categories (see Figure 8.30). One is born into a given subcaste, or community (called a jati), that traditionally defined much of one’s life experience—

caste system a complex, ancient Hindu system for dividing society into hereditary hierarchical classes

jati in Hindu India, the subcaste into which a person is born, which traditionally defines the individual’s experience for a lifetime

varna the four hierarchically ordered divisions of society in Hindu India underlying the caste system: Brahmins (priests), Kshatriyas (warriors/kings), Vaishyas (merchants/landowners), and Sudras (laborers/artisans)

Brahmins, members of the priestly caste, are the most advantaged in caste hierarchy. Thus they must conform to those behaviors that are considered most ritually pure (for example, strict vegetarianism and abstention from alcohol). As is the case with many castes, Brahmins are found in many occupations outside their place as priests in the varna system (as barbers and hairdressers, for example). Below Brahmins, in descending rank, are Kshatriyas, who are warriors and rulers; Vaishyas, who are landowning (small-

Although jatis are associated with specific subcategories of occupations, in modern economies, this aspect of caste is more symbolic than real. Members of a particular jati do, however, follow the same social and cultural customs, dress in a similar manner, speak the same dialect, and tend to live in particular neighborhoods or villages. This spatial separation arises from the higher-

It is important to note that caste and class are not the same thing. Class refers to economic status, and there are class differences within caste groups because of differences in wealth. Historically, upper-

Geographic Patterns of Religious Beliefs The geographic pattern of religion in South Asia is complex and overlapping. As Figure 8.12 shows, there is a core Hindu area in central India, with other faiths more common on the fringes of the region.

The approximately 520 million Muslims in South Asia form the majority in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and the Maldives; and the 140 million Muslims in India are a large and important minority, comprising 12 percent of the population. They live mostly in the northwestern and central Ganga River plain.

Buddhism began about 2600 years ago as an effort to reform and reinterpret Hinduism. Its origins are in northern India, where it flourished early in its history before spreading eastward to East and Southeast Asia. About 10 million people—

Buddhism a religion of Asia that originated in India in the sixth century B.C.E. as a reinterpretation of Hinduism; it emphasizes modest living and peaceful self-

Jainism, like Buddhism, originated as a reformist movement within Hinduism more than 2000 years ago. Jains (about 6 million people, or 0.6 percent of the region’s population) are found mainly in cities and in western India. They are known for their educational achievements, promotion of nonviolence, and strict vegetarianism.

Jainism a religion of Asia that originated as a reformist movement within Hinduism more than 2000 years ago; Jains are found mainly in western India and in large urban centers throughout the region and are known for their educational achievements, nonviolence, and strict vegetarianism

Sikhism was founded in the fifteenth century as a challenge to both Hindu and Islamic systems. Sikhs believe in one god, hold high ethical standards, and practice meditation. Philosophically, Sikhism accepts the Hindu idea of reincarnation but rejects the idea of caste. (In everyday life, however, caste plays a role in Sikh identity.) The 21 million Sikhs in the region live mainly in Punjab, in northwestern India. Their influence in India is greater than their numbers because throughout India many Sikhs hold positions in the government, in the military, and in police forces.

Sikhism a religion of South Asia that combines beliefs of Islam and Hinduism

The first Christians in the region are thought to have arrived in the far southern Indian state of Kerala with St. Thomas, the apostle of Jesus, in the first century c.e. Today, Christians and Jews are influential but tiny minorities along the west coast of India. A few Christians live on the Deccan Plateau and in northeastern India near Burma.

Animism, the most ancient religious tradition, is practiced throughout South Asia, especially in central and northeastern India, where there are indigenous people whose occupation of the area is so ancient that they are considered aboriginal inhabitants. (For a discussion of animism, see Chapter 7.)

Globalization and the Legacies of British Colonial Rule

As Mughal rule declined, a number of regional states and kingdoms rose and fought with one another (Figure 8.13). The absence of one strong power created an opening for yet another invasion. By the late 1700s, several European trading companies were competing to gain a foothold in the region. Of these, Britain’s East India Company was the most successful. By 1857, the East India Company, acting as an extension of the British government, repressed a rebellion against European intrusion and became the dominant power in the region.

The British controlled most of South Asia from the 1830s through 1947 (Figure 8.14). By making the region part of the British Empire, the British accelerated the process of globalization in South Asia, transforming the region politically, socially, and economically. Even areas not directly ruled by the British felt the influence of their empire. Afghanistan repelled British attempts at military conquest, but the British continued to intervene there, trying to make Afghanistan a “buffer state” between British India and Russia’s expanding empire. Nepal remained only nominally independent during the colonial period, and Bhutan became a protectorate of the British Indian government.

The Deindustrialization of South Asia As in their other colonies, the British used South Asia’s resources primarily for their own benefit, often with disastrous results for South Asians. One example was the fate of the textile industry in Bengal (modern-

Bengali weavers, long known for their high-

Many people who were pushed out of their traditional livelihood in textile manufacturing were compelled to find work as landless laborers. But rural South Asia already had an abundance of agricultural labor, so many migrated to emerging urban centers. In the 1830s, a drought worsened an already difficult situation and more than 10 million people starved to death. Throughout the nineteenth century, similar events forced millions of South Asian workers to join a stream of indentured laborers migrating to other British colonies in the Americas, Africa, Asia, and the Pacific, where their descendants can still be found.  183. CARIBBEAN BEAT PULSES WITH INDIAN ACCENTS

183. CARIBBEAN BEAT PULSES WITH INDIAN ACCENTS

Democratic and Authoritarian Legacies Contemporary South Asian governments retain institutions put in place by the British to administer their vast empire. These governments inherited many of the shortcomings of their colonial forebears, such as authoritarian bureaucratic procedures that tend to resist change. While the governments have proved functional over time, there have been numerous major civil disturbances in virtually every country. Democratic governments were not instituted on a large scale until the final days of the Empire, but since independence in 1947 (see below), people have been able to use the political freedoms afforded by democracy to voice their concerns and to make many peaceful transitions of elected governments. Still, the struggle to retain and build democratic institutions continues.

Independence and Partition The tremendous changes brought by the British inspired many resistance movements among South Asians. Some of these were militant movements intent on pushing the British out by force, such as the unsuccessful rebellion of South Asian soldiers employed by the British East India Company in 1857. Other movements, such as the Indian National Congress (founded in 1885), used political means to agitate for more democracy, which they saw as the route to South Asian political independence. Although both militant and political actions were brutally repressed, the democracy movements gained worldwide attention and, after decades of struggle, were successful.

Nonviolence as a Political Strategy In the early twentieth century, Mohandas Gandhi, a young lawyer from Gujarat—

civil disobedience protesting of laws or policies by peaceful direct action

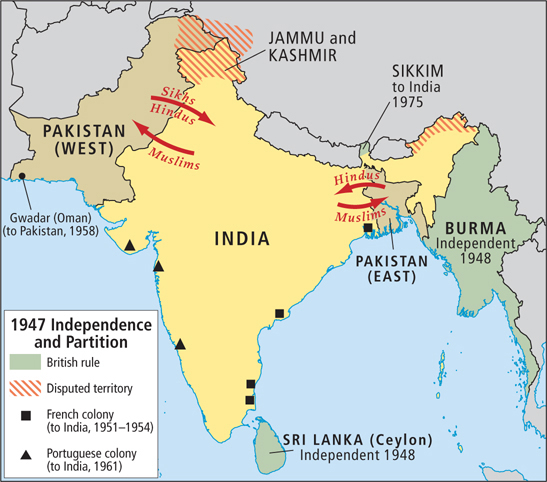

The Partition of India in 1947 When British India was granted independence by Britain in 1947, it was divided into two independent countries: India, which was predominantly Hindu; and West and East Pakistan, which was predominantly Muslim (Figure 8.15). (Afghanistan, Bhutan, and Nepal were never officially British colonies; Ceylon [now Sri Lanka] became independent in 1948.) This division—

Partition the breakup following Indian independence that resulted in the establishment of Hindu India and Muslim Pakistan

Muslim political leaders, concerned about the fate of a minority Muslim population in a united India with a Hindu majority, first suggested the idea of two nations. Though Partition was highly controversial, it became part of the independence agreement between the British and the Indian National Congress (India’s principal nationalist party). Northwestern and northeastern India, two very different places historically and culturally, but where the populations were predominantly Muslim, became a single country consisting of two parts known as West and East Pakistan, separated by northern India (see Figure 8.15). Although both India and Pakistan maintained secular constitutions with no official religious affiliation, the general understanding was that Pakistan would have a Muslim majority and India a Hindu majority. Fearing that they would be persecuted if they did not move, more than 7 million Hindus and Sikhs migrated to India from their ancestral homes in what had become West or East Pakistan. A similar number of Muslims left their homes in India for one of the parts of Pakistan. In the process, civil society broke down: Families and communities were divided, looting and rape were widespread, and between 1 and 3.4 million people were killed in numerous local outbreaks of violence. In 1971, after a bloody civil war, Pakistan was divided into Bangladesh (formerly East Pakistan) and Pakistan (formerly West Pakistan).  184. 60TH ANNIVERSARY OF INDIA–PAKISTAN PARTITION ON AUGUST 15TH

184. 60TH ANNIVERSARY OF INDIA–PAKISTAN PARTITION ON AUGUST 15TH

Partition was the tragic culmination of the divide-

The Post-

Under British rule, agricultural modernization lagged, and during World War II, the Bengal Famine took an estimated 4 million lives. After independence, progress in agricultural production was slow until the late 1960s, when the green revolution brought marked improvements (see later in this chapter). The move to modernized farming on large tracts of land with far fewer agricultural workers brought prosperity to some South Asians, relieved food scarcities, and made food exports possible; but it also forced millions to migrate to the cities. This migration intensified the already vast economic disparities in urban South Asia.

Industrialization became a main goal after independence, partly in response to the dismantling of industry during the colonial period. The emphasis on technical training has produced several generations of highly skilled engineers whose talents are in demand around the world. In most countries in the region, urban-

THINGS TO REMEMBER

The Indus Valley/Harappa civilization, which began 4500 years ago, was remarkable for its innovative developments in water management and agriculture.

South Asia has been invaded many times, primarily from the north by groups stretching from Greece to Mongolia.

There are many distinct ethnic groups in South Asia, each with its own language or dialect. Today, variants of Hindi are the principal languages of India and Pakistan, while Bengali is the official language of Bangladesh. English is a common second language throughout South Asia.

Caste and class are not the same thing: “Class” refers to economic status, and “caste” to hereditary hierarchical social categories. There are class differences within caste groups because of differences in wealth. Even though India’s constitution bans caste discrimination, caste is still hugely influential in Indian society.

There is a geographic pattern to religion in South Asia, but it is not absolute and people of different religions often live in close proximity. Relations between Muslims and Hindus can be quite tense, occasionally resulting in violent confrontation. Other religious traditions also play prominent local roles in the life of South Asia.

Page 338Following some 300 years of Mughal rule, the British controlled most of South Asia from the 1830s through 1947, profoundly influencing the region politically, socially, and economically.

British colonial rule in South Asia channeled resources to Europe, and in so doing depressed flourishing industries and inhibited development.

In the early twentieth century, Mohandas “Mahatma” Gandhi emerged as a central political leader of India’s independence movement, using nonviolent civil disobedience that eventually led to independence.

Instead of relieving tensions, Partition—

the 1947 division of British India into two countries, India and Pakistan— laid the groundwork for the repeated wars, skirmishes, strained relations, and ongoing arms race between India and Pakistan.