8.6 POWER AND POLITICS

GEOGRAPHIC INSIGHT 3

Power and Politics: India, South Asia’s oldest, largest, and strongest democracy, has shown that the expansion of political freedoms can ameliorate conflict. Across the region, when people have been able to participate in policy-

Throughout South Asia’s history, supporters of opposing political ideologies—

A particularly virulent source of conflict within all South Asian countries is corruption, often linked to purposeful bureaucratic inefficiency, especially the soliciting of bribes to perform a service. A number of movements to address conflict and corruption are becoming popular among the increasingly politically aware middle class. Because more people are now employed in the private sector instead of in government-

The Hindu–

But there is a dark side to the Hindu–

communal conflict a euphemism for religiously based violence in South Asia

VIGNETTE

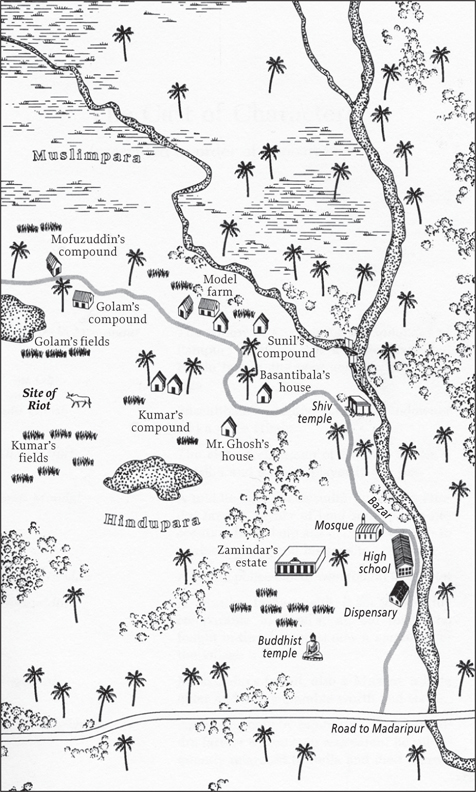

The sociologist Beth Roy, who studies communal conflict in South Asia, recounts an incident that she refers to as “Some trouble with cows” in the village of Panipur (a pseudonym) in Bangladesh (Figure 8.19). The incident started when a Muslim farmer either carelessly or provocatively allowed one of his cows to graze in the lentil field of a Hindu. The Hindu complained, and when the Muslim reacted complacently, the Hindu seized the offending cow. By nightfall, Hindus had allied themselves with the lentil farmer and Muslims with the owner of the cow. More Muslims and Hindus converged from the surrounding area, and soon there were thousands of potential combatants lined up facing each other. Fights broke out. The police were called. In the end, a few people died when the police fired into the crowd of rioters. [Source: Beth Roy. For detailed source information, see Text Sources and Credits.]

At the state and national level, Hindu–

Religious Nationalism

The association of a particular religion with a particular territory or political unit—

religious nationalism the association of a particular religion with a particular territory or political unit to the exclusion of other religions

Although both India and Pakistan were formally created as secular states, religious nationalism has been a reality in both countries, shaping relations between people and their governments. Rejecting the idea of multiculturalism, and referring back to the days of Partition, India is increasingly thought of as a Hindu state, while Pakistan calls itself an Islamic Republic, and Bangladesh a People’s Republic. In each country, many people in the dominant religious group strongly associate their religion with their national identity.

In India, urban men from middle-

Political parties based on religious nationalism have gained popularity throughout South Asia. Although their members think of these parties, such as the Bharatiya Janata Parishad (BJP) in India, as forces that will purge their country of corruption and violence, they are usually no less corrupt or violent than secular parties.

Movements Against Government Inefficiency and Corruption In recent years, reform movements have been developed by the many South Asians who have been frustrated by government inefficiency, corruption, religious nationalism, caste politics, and the failure of governments to deliver on their promises of broad-

Two aspects of the high-

The Growing Influence of Women and Young Voters

In the state elections of 2012, women and young voters were particularly active, coming to the polls in large numbers, with specific issues and candidates in mind. In several of the largest states, voter turnout was 50 percent higher than it had been in the past. The anticorruption movements mentioned above, widely covered in the press and by Web sites, apparently motivated voters. Large numbers of new voters, at least a third of whom are 18 to 19 years old, have recently registered to vote. These educated and urbanized voters, male and female, who have far more access to information than voters have had in the past, could usher in a new political era.

Regional Conflicts

The most intense armed conflicts in South Asia today are regional conflicts in which nations dispute territorial boundaries or a minority actively resists the authority of a national or state government. Most of these hostilities arise from the authoritarian tendencies of governments that at times work against the growth of political freedoms that might otherwise defuse political tensions.

regional conflict a conflict created by the resistance of a regional ethnic or religious minority to the authority of a national or state government; currently these are the most intense armed conflicts in South Asia

Conflict in Kashmir Since 1947 and the post-

THINKING GEOGRAPHICALLY

Use the Photo Essay above to answer these questions.

Question 8.14

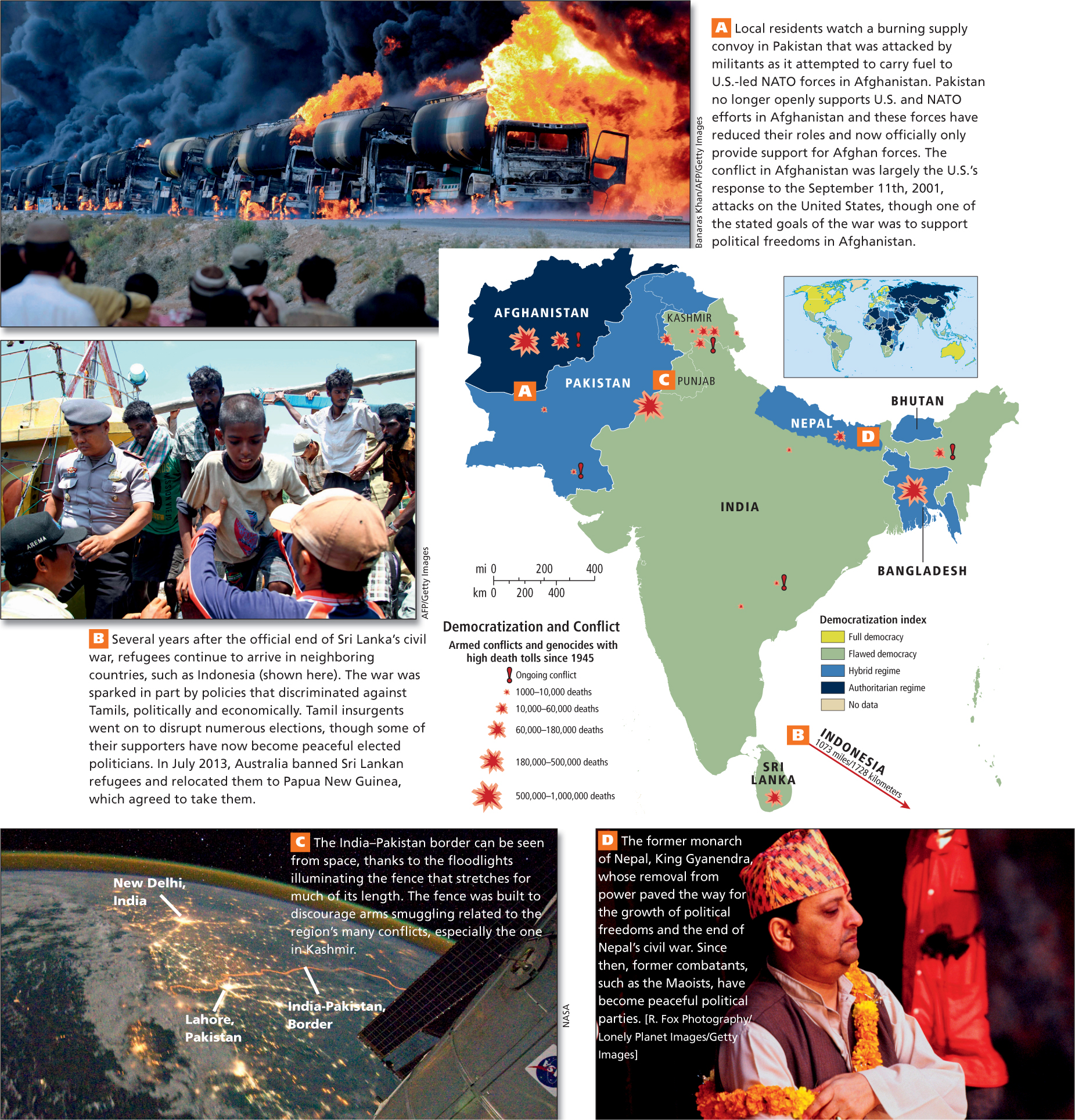

A What aspects of this photo suggest that the convoy is part of a government-

Question 8.15

C What direction was the camera facing when this photo was taken?

Question 8.16

D How did the Maoists describe the war they waged against King Gyanendra?

For many years, Kashmir has been a Muslim-

Pakistan attempted to invade Kashmir again in 1965 but was defeated. India and Pakistan are technically still waiting for a UN decision about the final location of the border (Figure 8.20C). The Ladakh region of Kashmir (see the Figure 8.1 map) is the object of a more limited border dispute between India and China.

After years of military occupation, most Kashmiris now support independence from both India and Pakistan. However, neither country is willing to hold a vote on the matter. Anti-

Another complication in the Kashmir dispute is the fact that both India and Pakistan—

War and Reconstruction in Afghanistan In the 1970s, political debate in Afghanistan became polarized. On one side were several factions of urban elites, who favored modernization and varying types of democratic reforms. Opposing them were rural, conservative religious leaders, whose positions as landholders and ethnic leaders were threatened by the proposed reforms. Divisions intensified as successive governments, all of which came to power through military coups, became more and more authoritarian. Political opponents were imprisoned, tortured, and killed by the thousands, resulting in a growing insurgency outside the major cities.

In 1979, fearing that a civil war in Afghanistan would destabilize neighboring Soviet republics in Central Asia, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan. Rural conservative leaders (often erroneously called “warlords”) and their followers formed an anti-

In 1989, after heavy losses—

In the early 1990s, a radical religious, political, and military movement called the Taliban emerged from among the mujahedeen. The Taliban wanted to control corruption and crime and minimize Western ways—

Following the events of September 11, 2001, the United States and its allies focused on removing the Taliban, who were giving shelter to Osama bin Laden and his international Al Qaeda network. By late 2001, the Taliban were overpowered by an alliance of Afghans supported heavily by the United States, the United Kingdom, and eventually by NATO (see the Figure 8.20 map).

In 2003, the United States launched the war in Iraq that diverted national attention, troops, and financial resources away from Afghanistan. Almost immediately the Taliban were back again, effectively thwarting the ability of Afghanistan’s new government to ensure security and to meet the needs of people outside Kabul. Based in rural areas in both Pakistan and Afghanistan, the Taliban are now aided by widespread distrust of the government in Kabul, which is seen as corrupt (see Figure 8.20A). It appears that most people in Afghanistan favor a democratic government based on Muslim principles, but functionally flawed elections beginning in 2004 have resulted in an ever-

In May of 2011, bin Laden was killed in a raid by U.S. forces in the town of Abbottabad, Pakistan. Another raid killed the next-

Sri Lanka’s Civil War The Singhalese have dominated Sri Lanka since their migration from Northern India several thousand years ago. Today they make up about 74 percent of Sri Lanka’s population of 20.5 million people. Most Singhalese are Buddhist. Tamils, a Hindu ethnic group from South India, make up about 18 percent of the total population of Sri Lanka. About half of these Tamils have been in Sri Lanka since the thirteenth century, when a Tamil Hindu kingdom was established in the northeastern part of the island. The other half were brought over by the British in the nineteenth century to work on tea, coffee, and rubber plantations. Some Tamils have done well, especially in urban areas, where they dominate the commercial sectors of the economy. However, many others have remained poor laborers isolated on rural plantations.

Upon its independence in 1948, Sri Lanka had a thriving economy led by a vibrant agricultural sector and a government that made significant investments in health care and education. It was poised to become one of Asia’s most developed economies. But, driven by nationalism, Singhalese was made the only official language and Tamil plantation workers were denied the right to vote. Efforts were also made to deport hundreds of thousands of Tamils to India. In the 1960s, the government shifted investment away from agricultural development and toward urban manufacturing and textile industries, which were dominated by Singhalese. By 1983, the Tamil minority, lacking political power and influence, chose to use guerilla warfare against the Singhalese, mounting an army known as the Tamil Tigers.

For more than 30 years, the entire island was subjected to repeated terrorist bombings and kidnappings. Peace agreements were attempted several times, but in the end it was an overwhelming military victory by the government, combined with an effective crackdown on international funding for the Tamils, that forced the Tamil surrender in May of 2009. However, dissatisfaction with the peace process has resulted in an ongoing flow of Tamil and other refugees from Sri Lanka (see Figure 8.20B).

Despite many years of violence that severely curtailed the tourist industry, economic growth in other sectors has been surprisingly robust in Sri Lanka. Driven by strong growth in food processing, textiles, and garment making, Sri Lanka is today one of the wealthiest nations in South Asia on a per capita GDP basis, and it provides for the human well-

Nepal’s Rebels After a civil war that ended generations of monarchical rule, Nepal has endured years of political turmoil. An elected legislature and multiparty democracy were introduced into Nepal in 1990, but until 2008, a royal family governed with little respect for the political freedoms of the Nepalese people.

In 1996, inspired by the ideals of the late Chinese leader Mao Zedong (but with no apparent support from China), Maoist revolutionaries took advantage of public discontent and waged a “people’s war” against the Nepalese monarchy. Following a decade of civil war, during which 13,000 Nepalese died, the Maoists had both military control of much of the countryside and strong political support from most Nepalese. Persistent poverty and lack of the most basic development under the dictatorial rule of the latest monarch, King Gyanendra (see Figure 8.20D), led to massive protests that forced Gyanendra to step down in 2006. Soon thereafter, the Maoists declared a cease-

In 2008, the Maoists won sweeping electoral victories that gave them a majority in parliament and made their former rebel leader prime minister. Then, in May of 2009, when his many conditions for reforming Nepalese society remained unmet, the Maoist prime minister resigned in a tactical parliamentary move and took his party into opposition against a new prime minister and his weak 22- 200. FUTURE OF NEPAL’S KING GYANENDRA IN QUESTION

200. FUTURE OF NEPAL’S KING GYANENDRA IN QUESTION

Caste and Politics Despite decades of effort to fight the influence of caste, politics in India are still dramatically influenced by caste. In the twentieth century, Mohandas Gandhi began an organized effort to eliminate discrimination against “untouchables.” As a result, India’s constitution bans caste discrimination. However, in recognition that caste is still hugely influential in society, India began an affirmative action program upon independence from Britain. The program reserves a portion of government jobs, places in higher education, and parliamentary seats for Dalits and Adivasis. Together, the two groups now constitute approximately 23 percent of the Indian population and are guaranteed 22.5 percent of government jobs. Extended in 1990, this program now includes other socially and educationally “backward castes” (the term used in India), such as disadvantaged jatis of the Sudras caste, allotting them an additional 27 percent of government jobs. However, reserving nearly half of government jobs in this way has resulted in considerable controversy. In 2006, medical students successfully protested against quotas in elite higher-

At the local level, most political parties design their vote-

Among educated people in urban areas, the campaign to eradicate discrimination on the basis of caste may appear to have succeeded, but the reality is more complex. Throughout the country, there are now some Dalits serving in powerful government positions. Members of high and low castes ride city buses side by side, eat together in restaurants, and attend the same schools and universities. For some urban Indians—

THINGS TO REMEMBER

GEOGRAPHIC INSIGHT 3

Power and Politics India, South Asia’s oldest, largest, and strongest democracy, has shown that the expansion of political freedoms can ameliorate conflict. Across the region, when people have been able to participate in policy-

making decisions and implementation— especially at the local level— seemingly intractable conflict has been diffused and combatants have been willing to take part in peaceful political processes. Religious nationalist movements are increasingly attractive to people frustrated by government inefficiency, corruption, and caste politics, and by the failure of governments to deliver on their promises of broad-

based prosperity. New populations of voters—

women and educated youth— are changing the outcomes of elections across the region. The most intense armed conflicts in South Asia today are regional conflicts in which nations dispute territorial boundaries or a minority actively resists the authority of a national or state government.

Despite decades of effort to fight its influence, caste still dramatically affects politics in India.