8.7 URBANIZATION

GEOGRAPHIC INSIGHT 4

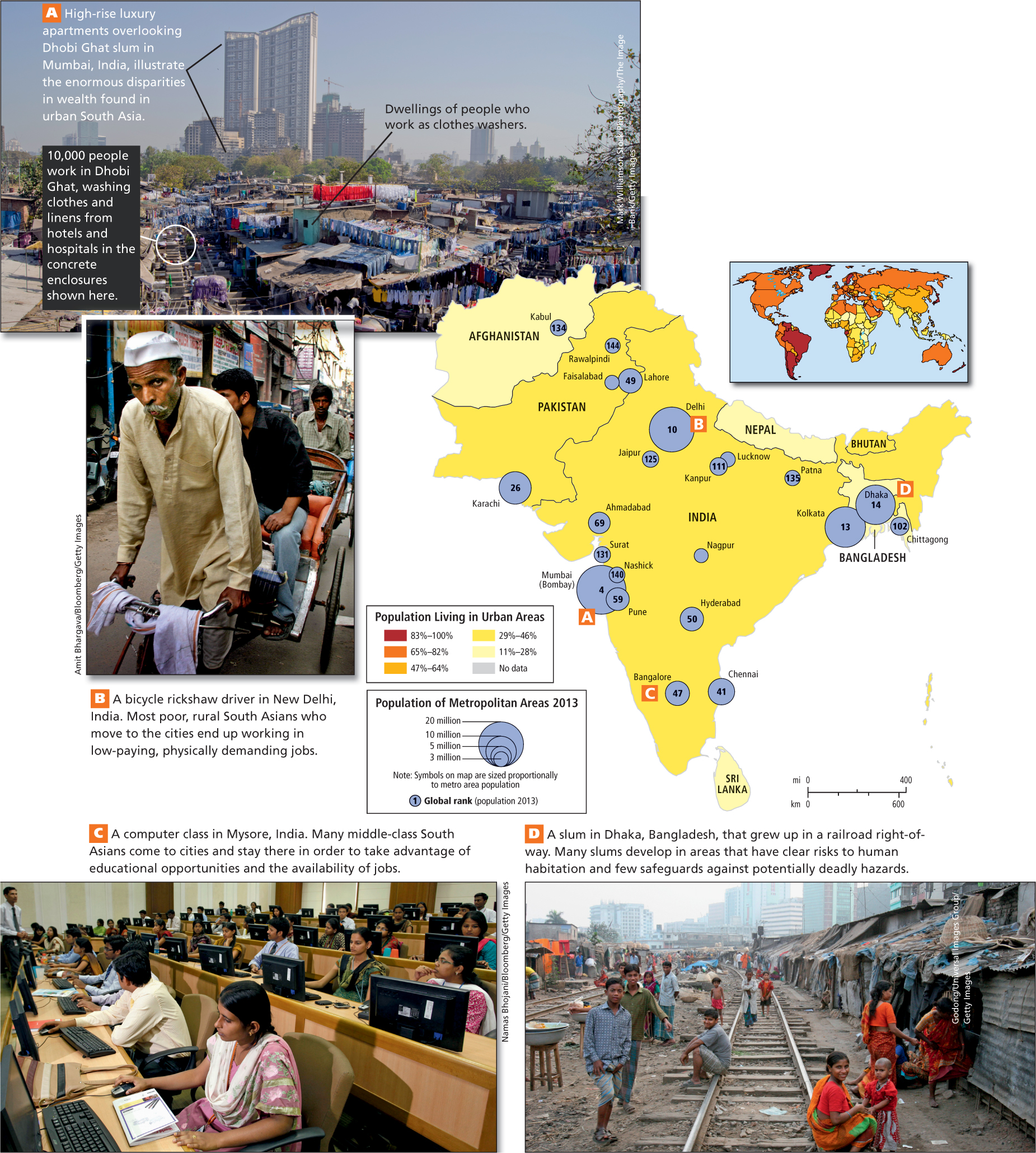

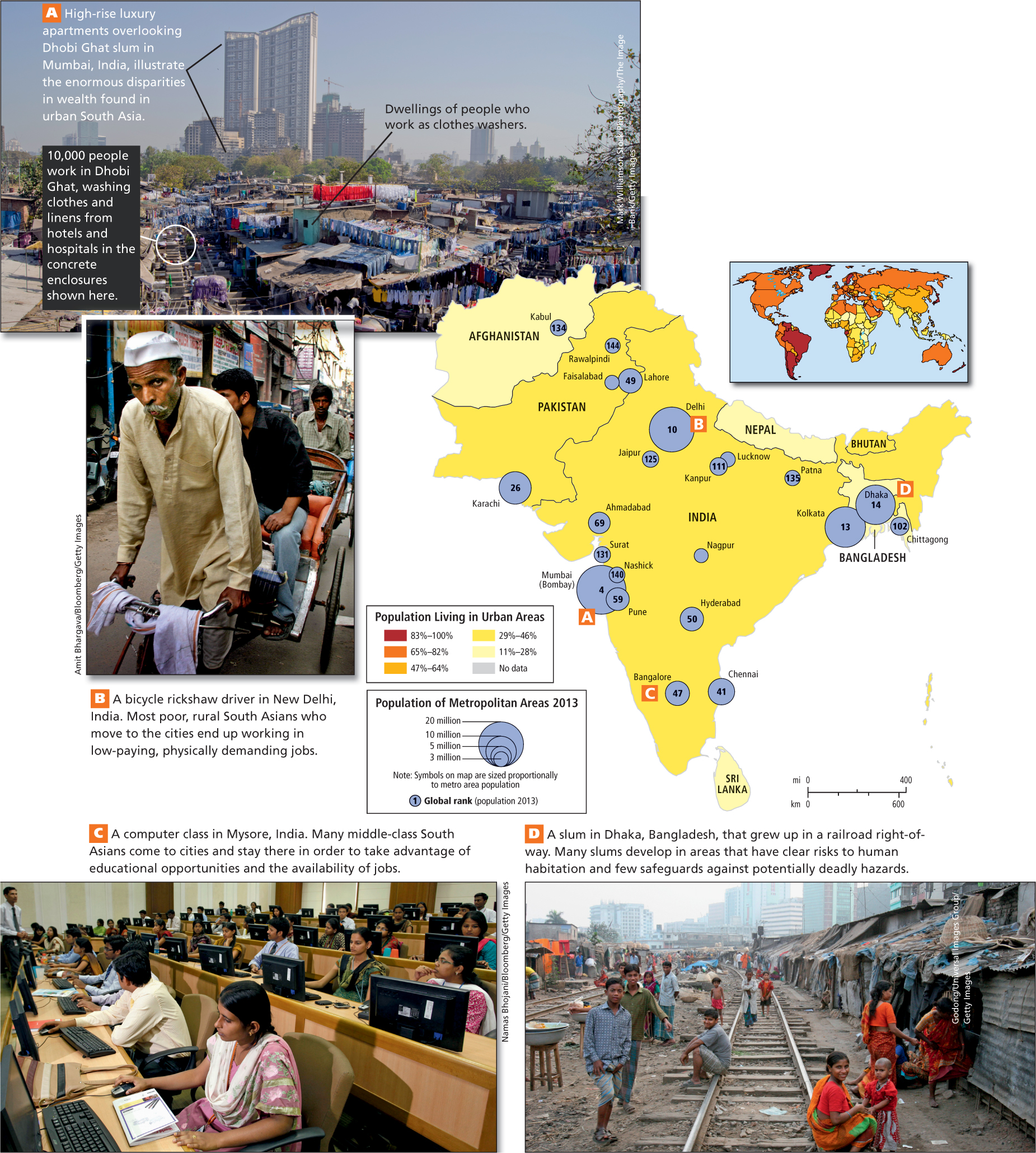

Urbanization: South Asia has two general patterns of urbanization: one for the rich and the middle classes and one for the poor. The areas that the rich and the middle classes occupy include sleek, modern skyscrapers bearing the logos of powerful global companies, universities, upscale shopping districts, and well-appointed apartment buildings. The areas that the urban poor occupy are chaotic, crowded, and violent, with overstressed infrastructures and menial jobs. These two patterns often coexist in very close proximity.

Although today only 30 percent of the region’s population lives in urban areas, South Asia has several of the world’s largest metropolitan areas. By 2012, Mumbai had 22.9 million people; Kolkata, 16 million; Delhi, 19.5 million; Dhaka, 15.4 million; and Karachi, 11.1 million. All of these cities have grown quickly and all now have massive slums (Figure 8.21D). This growth is likely to continue, and South Asia’s current urban population of about 460 million people could expand to as many as 712 million by 2025.

Figure 8.21: FIGURE 8.21 PHOTO ESSAY: Urbanization in South AsiaWhile only 30 percent of South Asia’s population is urban, the region is home to some of the world’s largest cities, such as Mumbai, Delhi, Dhaka, Kolkata, and Karachi. Throughout the area, between 50 and 90 percent of the urban population live in slums plagued by shoddy construction and inadequate access to water and sanitation.

THINKING GEOGRAPHICALLY

Use the Photo Essay above to answer these questions.

Many middle-class South Asians move to cities for education, training, or business opportunities (Figure 8.21C). Because people come to cities where schooling is more available, large cities have higher literacy rates than rural areas. Mumbai and Delhi both have literacy rates above 80 percent, approximately 25 percent above the average for the country; Dhaka, in Bangladesh, and Karachi, in Pakistan, both have 63 percent literacy, more than 15 percent above the rate for each country as a whole.

Mumbai

Bombay is the name by which most Westerners know South Asia’s wealthiest city. It is now called Mumbai, after the Hindu goddess Mumbadevi. Mumbai has the largest deepwater harbor on India’s west coast. With more than 21 million people, its metropolitan area hosts India’s largest stock exchange, has multiple IT firms, and is the home of the nation’s central bank. It pays about a third of the taxes collected in the entire country and brings in nearly 40 percent of India’s trade revenue. Its annual per capita GDP is three times that of India’s next wealthiest city, the capital Delhi.

Mumbai’s wealth also extends into the realm of culture through the city’s flourishing creative arts industries, including its internationally known film industry. The city is known as “Bollywood” because it produces popular Hindi movies portraying love, betrayal, and family conflicts. (The term Bollywood is a combination of Bombay and Hollywood.) The stories, played out on lavish sets and accompanied by popular music and dance, serve to temporarily distract their huge audiences from the physical difficulties of daily life.

Mumbai’s wealth is most evident when one looks up at the elegant high-rise condominiums built for the city’s rapidly growing middle class. But at street level, the urban landscape is dominated by large numbers of people living on the sidewalks, in narrow spaces between buildings, and in large, rambling shantytowns (see Figure 8.21A). The largest of the shantytowns is Dharavi, which houses up to a million people in less than 1 square mile. It is said to contain 15,000 one-room factories turning out thousands of products that are sold in the global marketplace, many of them from India’s recycled plastic and metal. Dharavi rivals Orangi Township in Karachi, Pakistan, for the title of Asia’s most populous slum, but it is also generating future members of the middle class, at least among the factory owners.

There is yet a third aspect to urban life in South Asia. Were one to carefully observe places as widely separated and culturally different as Mumbai, Chennai, Kathmandu, and Peshawar, one would discover that beyond the main avenues and shantytowns, these cities also contain thousands of tightly compacted, reconstituted villages where daily life is intimate and familiar, not anonymous as in Western cities. Koli is one such place (see the vignette below).

As it is doing in sub-Saharan Africa, the cell phone is bringing urban-style communication into the South Asian countryside. Mumbai-based reporter Anand Giridharadas found that over half the population of South Asia now has access to a cell phone. Even though this access is unevenly distributed, for many the cell phone has become a means of creating the type of social privacy that the bedroom stands for in Western life. With a cell phone, a person can conduct relationships, keep secrets, and access information, all while avoiding interference from authority figures. One measure of how rapidly cell phone technology has taken over is that many more South Asians now have a cell phone than have the use of a flush toilet. Indeed, many young South Asians now view IT access as essential.

Risks to Children in Urban Settings In rural areas, a child can perform useful tasks by age 5, thereby contributing to family well-being. But what about children in urban areas? A report by the International Labor Organization (2008) found that 23 million children between the ages of 5 and 14 are working in South Asia, many of them in urban areas. They work primarily in the informal sector as domestic servants; in export-oriented factories like those small enterprises in urban slums; and as dump scavengers. Some are forced into the sex trade. Clearly, many of these occupations are entirely unsafe and inappropriate for children, who should be protected from such exploitation.

But if we look more closely at one occupation that children have, that of carpet weaving, some interesting issues arise. Carpet weaving is an ancient artistic and economic enterprise in South Asia; traditionally, it has been a family-run enterprise, with women and children as weavers and men as merchants. For thousands of years, young children have learned weaving skills from their parents and have become proud members of the family’s home-based production unit. But in today’s rapidly modernizing society, the role of children as family workers must be balanced with the need for children to attend school. One of the chief benefits of urban life is education, where children learn the skills that will enable them to survive and prosper in a modern economy, such as the ability to read, write, and do basic math.

Page 349

Page 350

As global trade has increased the demand for fine, hand-woven carpets, most of the profit has gone not to the weaving families but to South Asian middlemen and foreign traders from Europe and America. The possibility of making large profits has led some unscrupulous carpet merchants to set up factories where kidnapped children are forced to produce carpets. Obviously, kidnapping and enslavement must be stopped, but the question remains: Is there room for cottage industry employment of children within the family circle?

VIGNETTE

Koli is an ancient fishing village that predates the city of Mumbai and is now squeezed between Mumbai’s elegant coastal high-rises and the Bay of Mumbai (Figure 8.22). Ringed by fishing boats, Koli is a labyrinth of low-slung, tightly packed homes. Some villagers still fish every day. The screeching of taxis and buses is soon lost in quiet calm as one ducks into a narrow covered passageway that winds through the village and branches in multiple directions. At first Koli appears impoverished, but inside, well-appointed homes, some with marble floors, TVs, and computers, open onto the dimly lit but pleasant alleys. The visitor soon learns that this is no slum or warren of destitute shanties, but rather a community of educated bureaucrats, tradespeople, and artisans who constitute South Asia’s rising urban middle class. [Source: From the field notes of Lydia and Alex Pulsipher and their colleague, Tom Osmand].

Figure 8.22: The village of Koli. Now surrounded by the vibrant city of Mumbai, in 1534 when the Portuguese colonists arrived, Koli was a small fishing settlement on a beautiful bay. The village remains and there are still some fishers in Koli, but this exterior view of Koli is misleading. In the interior, out of sight to strangers, dwellings have been rebuilt and refurbished. Most residents are educated and work as bureaucrats or in the service sector of the city.

[Alex Pulsipher]

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

Can Child Labor Be “Fair Labor”?

The United Nations, South Asian governments, and NGOs like RugMark are now addressing this issue of child labor in the hand-woven carpet industry. They have instituted an active program to curb child labor abuses while remaining open to the positive experience for a child of learning a skill and being part of a family production unit. India has established a national system to certify that exported carpets are made in shops where the children go to school, have an adequate midday meal, and receive basic health care. Such carpets bear the label “Kaleen” or “RugMark.”

Risks to Women and Men in Urban Settings When rural adults move to cities, the need to find a way to make a living, the crowded conditions, the lack of housing, and the welter of new experiences can leave them vulnerable to exploitation.

Women’s experience with purdah (seclusion) can leave them especially at risk. It is inexperienced and undereducated rural women and girls who are most often recruited or forced into sex work, the selling of sexual acts for a fee. The vast, urban, slum-based brothels in which sex workers work are legendary in the cities of South Asia and have been documented in, among other places, Half the Sky, a book and video by Nicholas Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn.

sex work the provision of sexual acts for a fee

Brothels are notoriously exploitative of women wherever they are found; but the age of the mobile phone is changing the geography of sex work, at once allowing sex workers to move out of brothels, control those who will become their clients, and manage their incomes, which used to be seized by pimps and madams. However, being spatially autonomous also leaves them less likely to have access to condoms or to learning about how to avoid HIV exposure, for which sex workers are at high risk.

Rural men new to cities are also at risk: On-the-job accidents, exposure to HIV, extreme pressure to support families on tiny wages by working long hours at physically demanding jobs (see Figure 8.21B), and the loss of camaraderie with fellow villagers are just a few of the hardships felt by men.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Urbanization South Asia has two general patterns of urbanization: one for the rich and the middle classes and one for the poor. The areas that the rich and the middle classes occupy include sleek, modern skyscrapers bearing the logos of powerful global companies, universities, upscale shopping districts, and well-appointed apartment buildings. The areas that the urban poor occupy are chaotic, crowded, and violent, with overstressed infrastructures and menial jobs. These two patterns often coexist in very close proximity.

Mumbai is South Asia’s wealthiest city and is a showcase of the economic disparity that characterizes South Asian cities.

Some South Asian urban neighborhoods share many of the intimate qualities of village life.

When rural people move to cities, the loss of village constraints on behavior, the need to find a way to make a living, the crowded conditions, the lack of housing, and the welter of new experiences can leave them vulnerable to exploitation.

Page 351