8.9 SOCIOCULTURAL ISSUES

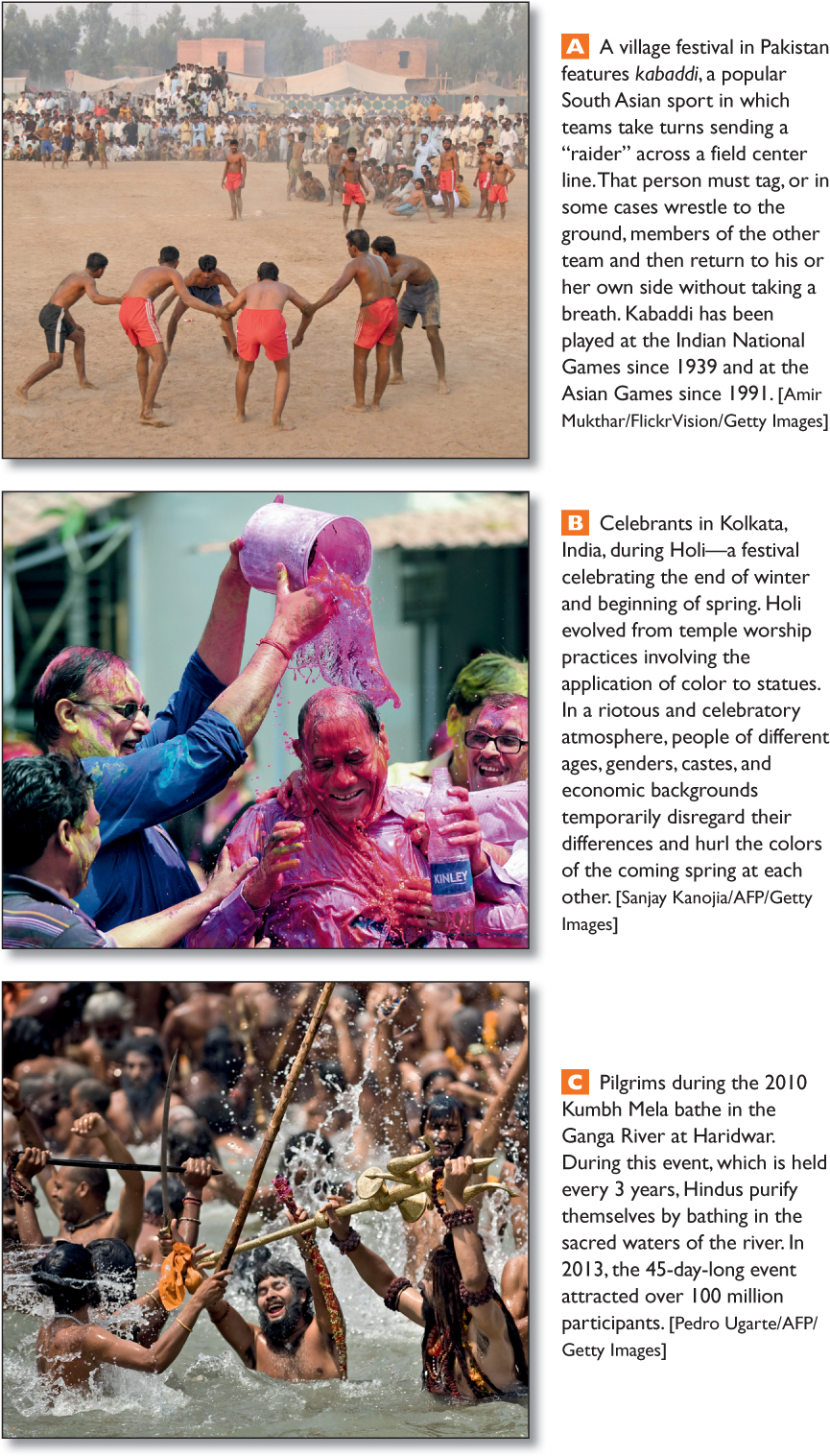

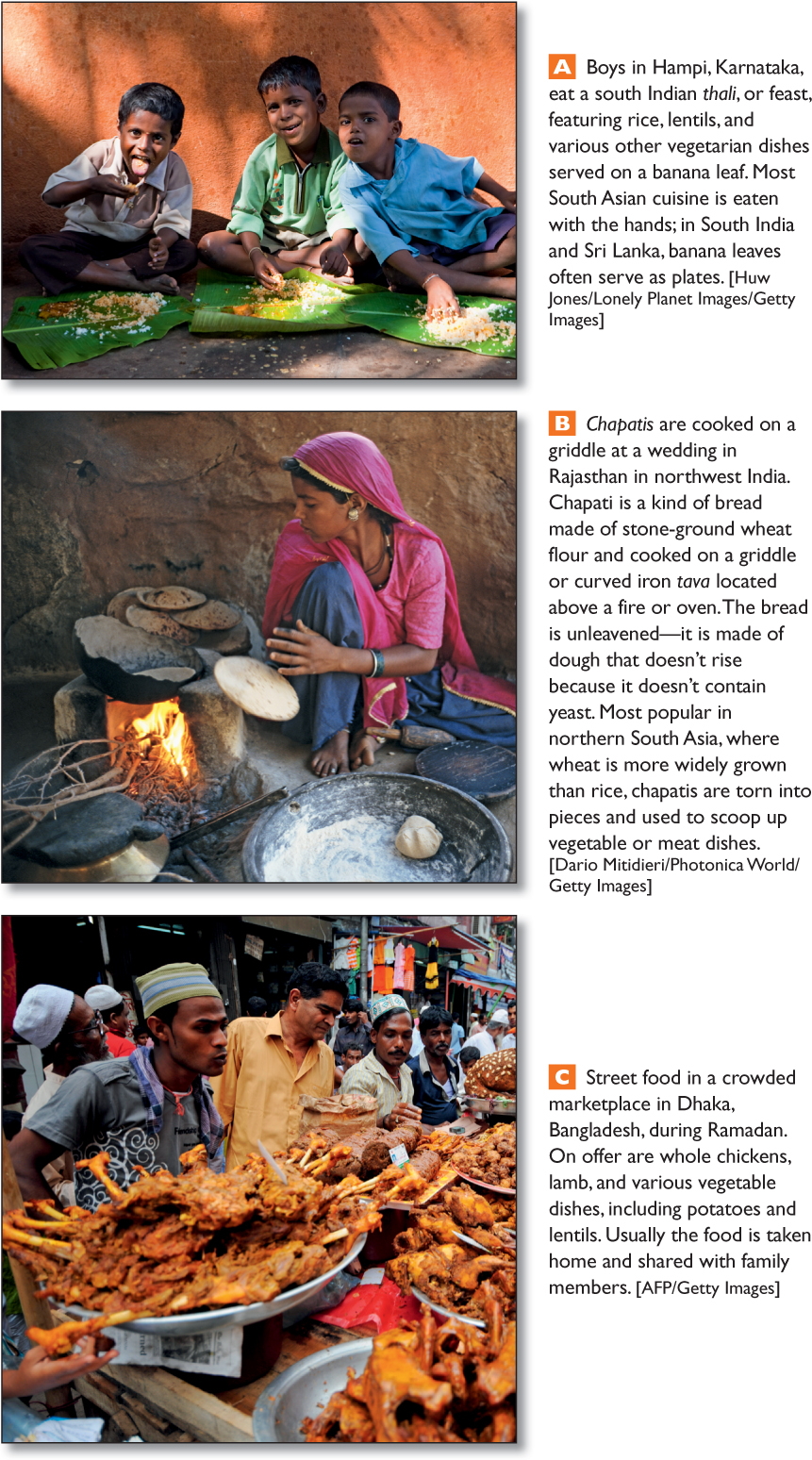

Within the life of one South Asian village or urban neighborhood, there can be considerable cultural variety. Differences based on caste, economic class, ethnic background, gender, religion, and even language are usually accommodated peacefully by longstanding customs, such as religious and ethnic festivals and food-

The Texture of Village Life

The vast majority—

VIGNETTE

The writer Richard Critchfield, who studied village life in more than a dozen countries, wrote that the village of Joypur (Bangladesh) in the Ganga-

In the early evening, mist rises above the rice paddies and hangs there “like steam over a vat.” It is then that the village comes to life, at least for the men. The men and boys return from the fields, and after a meal in their home courtyards, the men come “to settle in groups before one of the open pavilions in the village center and talk—

VIGNETTE

The anthropologist Faith D’Aluisio and her colleague Peter Menzel offer another peek into village life as night falls in Ahraura, a village in the state of Uttar Pradesh in north-

That Mishri can observe purdah is a mark of status because it shows she need not help her husband in the fields. Within the compound, she works from sunup to sundown, chatting only momentarily with two women who cover their faces and scurry from their own courtyards to hers for the short visit. Mishri is devoted to her husband, who was chosen for her by her family when she was 10; out of respect, she never says his name aloud. [Source: Adapted from Faith D’Aluisio and Peter Menzel, Women in the Material World, 1996.]

Social Patterns in the Status of Women

The status of women in South Asia varies significantly along rural/urban and religious divides. Generally speaking, rural women have far less freedom than do urban women. In rural India, middle-

Purdah The practice of concealing women from the eyes of nonfamily men, especially during women’s reproductive years, is known as purdah. It is observed in various ways across the region. The practice is strongest in Afghanistan and across the Indo-

purdah the practice of concealing women from the eyes of nonfamily men

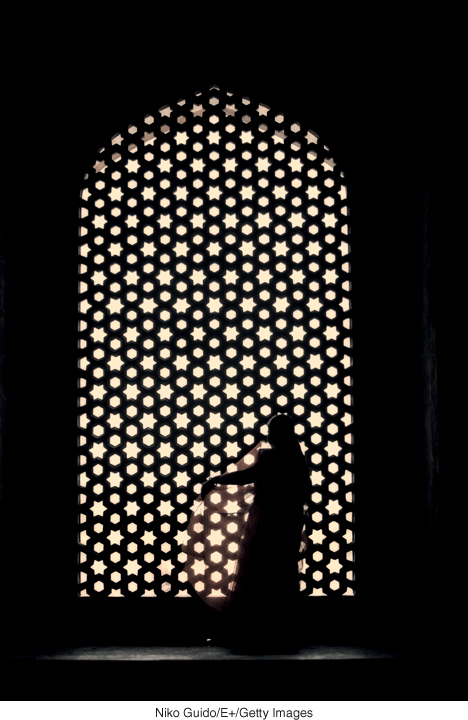

Purdah practices have influenced the architecture of South Asia. Homes are often in walled compounds that seclude kitchens and laundries as women’s spaces. In grander homes, windows to the street are usually covered with lattice screens, known as jalee, that allow in air and light but shield women from the view of outsiders.

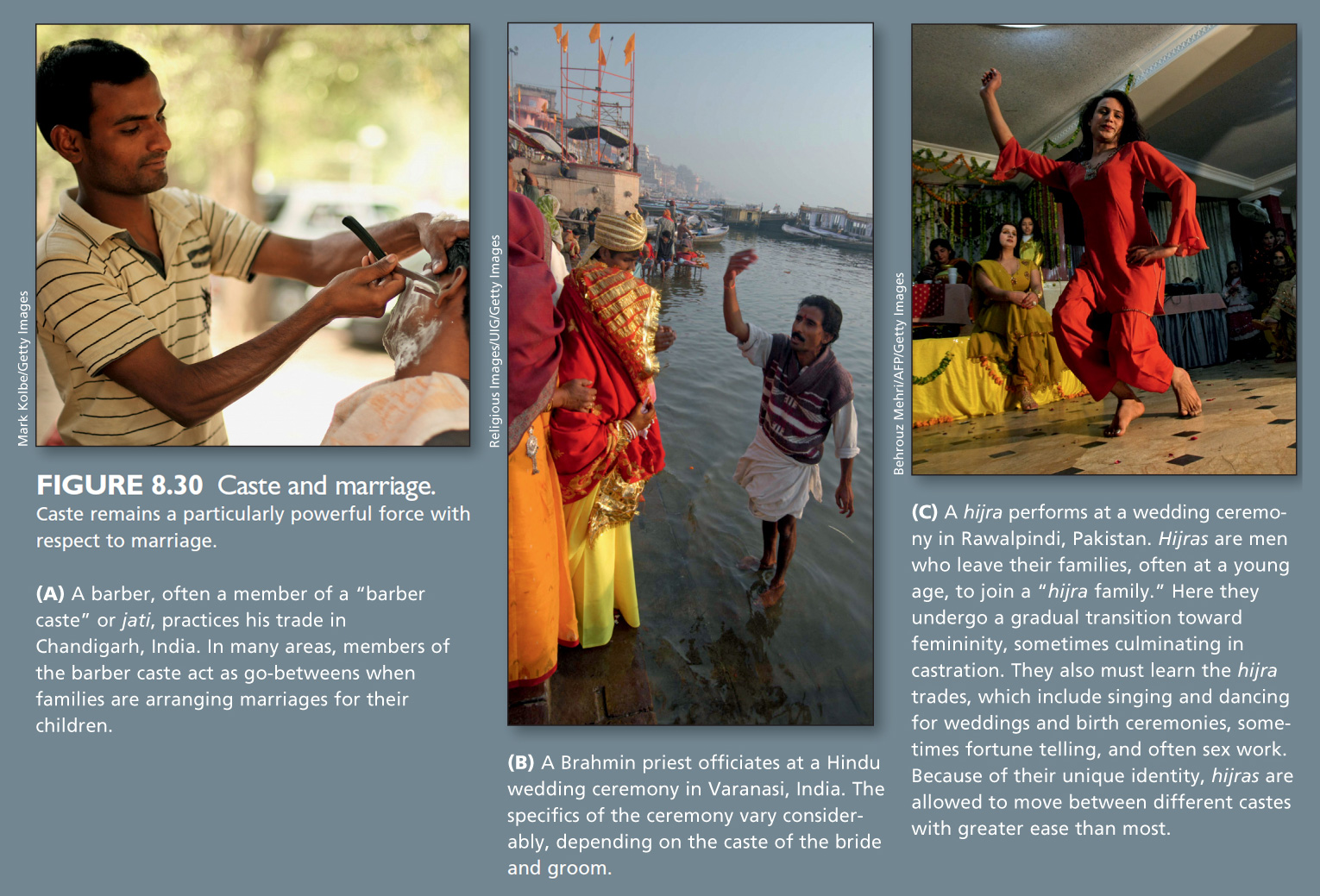

Marriage, Motherhood, and Widowhood Throughout South Asia, most marriages are arranged by the parents of the prospective bride and groom. Particularly in wealthier, better-

Usually a bride goes to live in her husband’s family compound, where she becomes a source of domestic labor for her mother-

Motherhood in South Asia determines much about a woman’s status within her community. A woman’s power and mobility increase when she has grown children and becomes a mother-

Dowry and Violence Against Females A dowry is a sum of money paid by the bride’s family to the groom’s family at the time of marriage. Dowries originated as an exchange of wealth between Muslim landowners or high-

dowry a price paid by the family of the bride to the groom (the opposite of bride price); formerly a custom practiced only by the rich

Until the last several decades, only wealthy families gave the groom a dowry—

Ironically, the increases in affluence and education have reinforced the custom of dowry and made it much more common for all families. As more men became educated, their families felt that their diplomas increased their worth as husbands and gave them the power to demand larger and larger dowries. Soon, the practice spread through lower-

Gender, Politics, and Power

As countries in South Asia have moved toward greater respect for political freedoms, the status of women in the region has risen. India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka have all had female heads of state (prime ministers) in the past. However, it is important to note that all of these women were either wives or daughters of previous heads of state. Women have been notably less successful in local elections, and at the parliamentary level Indian and Sri Lankan women remain very poorly represented (Table 8.2).

|

Country |

Percentage in Parliament |

|---|---|

|

Sri Lanka |

5.8 |

|

Bhutan |

8.5 |

|

Pakistan |

19.5 |

|

Nepal |

33.2 |

|

Bangladesh |

19.7 |

|

India |

11.0 |

|

Afghanistan |

27.7 |

Source: Women in National Parliaments, Inter-

The very low percentage of women in India’s parliament inspired a confederation of Muslim and Hindu women’s groups to lobby for legislation that would temporarily (for a 15-

If recent voter turnout and political activism trends continue, as discussed earlier in this chapter, there is likely to be a major improvement in female representation in the region’s national parliaments and in local offices.

Women and the Taliban in Afghanistan Women in Afghanistan have frequently suffered brutal repression since a conservative Islamist movement, the Taliban, gained control of the government there in the mid-

Taliban an archconservative Islamist movement that gained control of the government of Afghanistan in the mid-

VIGNETTE

From behind her microphone at Radio Sahar (“Dawn”), Nurbegum Sa‘idi speaks to a female audience on a wide range of topics. Located in the city of Herat, Radio Sahar is one in a network of independent women’s community radio stations that has sprung up in Afghanistan since early 2003. Radio Sahar provides 13 hours of daily programming consisting of educational items that address cultural, social, and humanitarian matters as well as music and entertainment. For example, one recent broadcast aimed at informing women of their legal rights followed the life of a young woman who was physically abused by her husband and his entire family. The woman took the brave step of asking for a divorce. As a result, she was forced into hiding, where she was counseled on the steps she might take next. A reported 600,000 Afghan women and youth listen to Radio Sahar while they do their chores.

Girls on the Air, a film by Valentina Monti, reveals the diversity of the ideas and hopes for the future of the young journalists who founded Radio Sahar. A clip can be seen at http:/

Men and the Taliban in Afghanistan The extreme repression of male individuality under the Taliban bears recognition for the hardships it causes. Hypermasculine societies, such as that of the Taliban, tend to repress creativity and emotional sensitivity in males, and that repression can lead to closed minds and even violence toward others, particularly women. Nevertheless, despite the many expressions of hypermasculinity in Afghanistan, Pakistan, and elsewhere in this region, there is also a long history of alternative expressions of gender (see Figure 8.30C).

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

Cell Phones and Literacy

In order to reach women held in deep seclusion, the Afghan government is now making available basic reading and writing lessons on special mobile phones distributed free to Afghan women. The reading/writing software was developed by an Afghan IT firm with USAID assistance. As a woman achieves literacy, she can add other subjects with free apps.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Purdah is practiced in both Muslim and Hindu households, but the status of Muslim women is significantly lower than that of their Hindu, Sikh, Jain, Buddhist, and Christian counterparts.

Changing dowry customs appear to be a cause of the growing incidence of various kinds of domestic violence against females in Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh.

Motherhood in South Asia determines much about a woman’s status within her community.

South Asia has had a number of women in very high positions of power, and young women today on average have more educational and employment opportunities than women of a generation ago. However, the overall status of women in the region is notably lower than the status of men.

187. SUFI ROCK SINGER FALU BLENDS OLD WITH NEW

187. SUFI ROCK SINGER FALU BLENDS OLD WITH NEW