9.8 POPULATION AND GENDER

GEOGRAPHIC INSIGHT 5

Population and Gender: Although East Asia remains the most populous world region, families here are having far fewer children than in the past, resulting in populations that are aging. Meanwhile, the legacy of China’s now largely abandoned “one child” policy, combined with an enduring cultural preference in China for male children, has created a shortage of females.

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

Shanghai’s Pajama Culture

Shanghai’s long-

Of all world regions, only Europe has a lower rate of natural increase than that of East Asia (less than 0.0 percent increase per year, compared to East Asia’s 0.4 percent). In China, this is partially due to the legacy of government policies that harshly penalized families for having more than one child. But in China as well as elsewhere, urbanization and changing gender roles are also resulting in smaller families, regardless of official policy. Only in the two poorest countries—

Responding to an Aging Population

Low birth rates mean that fewer young people are being added to the population, and improved living conditions mean that people are living longer across East Asia. The overall effect is that the average age of the populations is rising. Put another way, populations are aging. For Mongolia, South Korea, North Korea, and Taiwan, it will be several decades before the financial and social costs of supporting numerous elderly people will have to be addressed. China faces especially serious future problems with elder care because the one-

Japan’s Options Japan’s population is growing slowly and aging rapidly, raising concerns about economic productivity and humane ways to care for dependent people. The demographic transition (see Chapter 1) is well underway in this highly developed country, where 86 percent of the population lives in cities. Japan has a negative rate of natural increase (-0.2), the lowest in East Asia and on par with that of Europe. If this trend continues, Japan’s population is projected to plummet from the current 128 million to 95.5 million by 2050.

At the same time, the Japanese have the world’s longest life expectancy, at 83 years (Figure 9.23). As a result, Japan also has the world’s oldest population, 24 percent of which is over the age of 65. By 2055, this age group will account for approximately 40 percent of the population. By 2050, Japan’s labor pool could be reduced by more than a third, but it would still need to produce enough to take care of more than twice as many retirees as it does now. Clearly, these demographic changes will have a momentous effect on Japan’s economy, and the search for solutions is underway. One possibility is increasing immigration to bring in younger workers who will fill jobs and contribute to the tax rolls, as the United States and Europe have done.

In Japan, recruiting immigrant workers from other countries is a very unpopular solution to the aging crisis. Many Japanese people object to the presence of foreigners, and the few small minority populations with cultural connections to China or Korea have for years faced discrimination. The children of foreigners born in Japan are not granted citizenship, and some who have been in the country for generations are still thought of as foreign. Today, immigrants must carry an “alien registration card” at all times.

Nonetheless, foreign workers are dribbling into Japan in a multitude of legal and illegal ways. Many are so-

In a novel approach to Japan’s demographic changes, the government has invested enormous sums of money in robotics over the past decade. Robots are already widespread in Japanese industries such as auto manufacturing, and their industrial use is growing. Now they are also being developed to care for the elderly, to guide patients through hospitals, to look after children, and even to make sushi. By 2025, the government plans to replace up to 15 percent of Japan’s workforce with robots.

China’s Options The proportion of China’s population over 65 is now only 9 percent, but this will change rapidly as conditions improve and life expectancies increase by 5 to 10 years to become more like those of China’s affluent East Asian neighbors. However, a crisis in elder care is already upon China for two other reasons: the high rate of rural-

When hundreds of millions of young Chinese people were lured into cities to work, most thought rural areas would benefit from remittances, and this has happened. However, few anticipated that the one-

The Legacies of China’s One-Child Policy

In response to fears about overpopulation and environmental stress, China had a one-

The one-

The one-

Gender Imbalance and the Cultural Preference for Sons: Missing Females and Lonely Males The one-

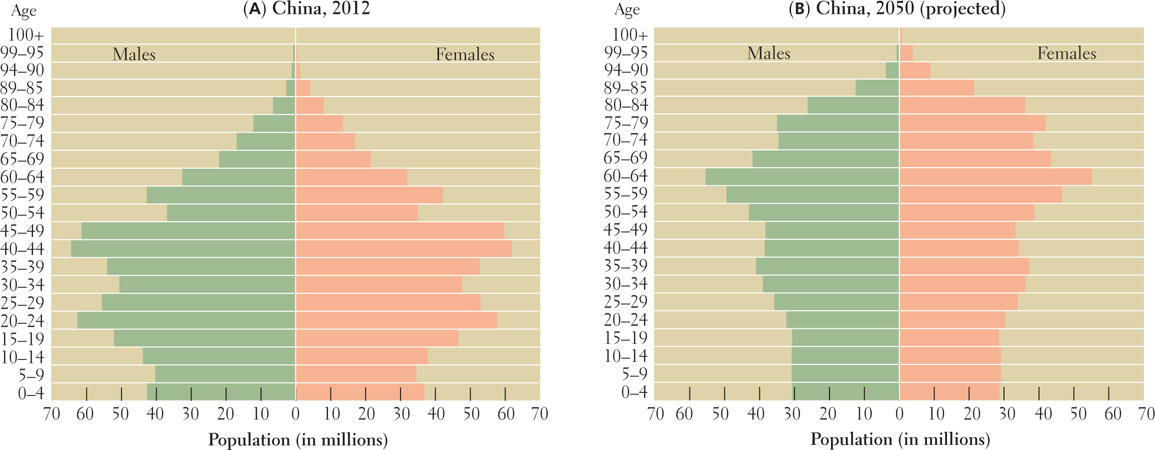

China’s more severe gender imbalance is illustrated by its population pyramid (Figure 9.24A). The average global sex ratio at birth is 105 boys to 100 girls, which evens out to 101 boys to 100 girls by the age of 5. In China, however, there are 113 boys for every 100 girls born. In fact, for nearly every category until age 70, males outnumber females. The census data show that there are already 50 million more men than women.

What happened to the missing girls? There are several possible answers. Given the preference for male children, the births of these girls may simply have gone unreported by families hoping to conceal their daughters as they tried to conceive a male child. There are many anecdotes of girls being raised secretly or even disguised as boys. Also, adoption records indicate that girls are given up for international adoption much more often than boys are. Or the girls may have died in early infancy, either through neglect or infanticide. Finally, some parents have access to medical tests that can identify the sex of a fetus. There is evidence that in China, as elsewhere around the world, many parents choose to abort female fetuses.

There is some evidence that attitudes may be changing. For example, in Japan, South Korea, and Mongolia, the percentage of women receiving secondary education equals or exceeds that of men. In Japan, there is a slight gender imbalance in favor of females. In China, the makers of social policy have tried for decades to eliminate the old Confucian bias toward men by empowering women economically and socially. In some ways, they are succeeding, as Chinese women now participate in the workforce to a large degree. Nevertheless, the preference for sons persists.

A Shortage of Brides A major side effect of the preference for sons is that there is now a growing shortage of women of marriageable age throughout East Asia. In 2012, China alone had an estimated deficit of 11 million women aged 20 to 35. Females are also effectively “missing” from the marriage rolls because many educated young women are too busy with career success to meet eligible young men.

Research suggests that at least 10 percent of young Chinese men will fail to find a mate; and poor, rural, uneducated men will have the most difficulty. The shortage of women will lower the birth rate yet further, which will contribute to the expected shrinkage of the population over the next century. Without spouses, children, or even siblings, there will be no one to care for single men when they age. Furthermore, China’s growing millions of single young men are emerging as a potential threat to civil order, as they may be more prone to drug abuse, violent crime, HIV infection, and sex crimes. Cases of kidnapping and forced prostitution of young girls and women are already increasing.

Population Distribution

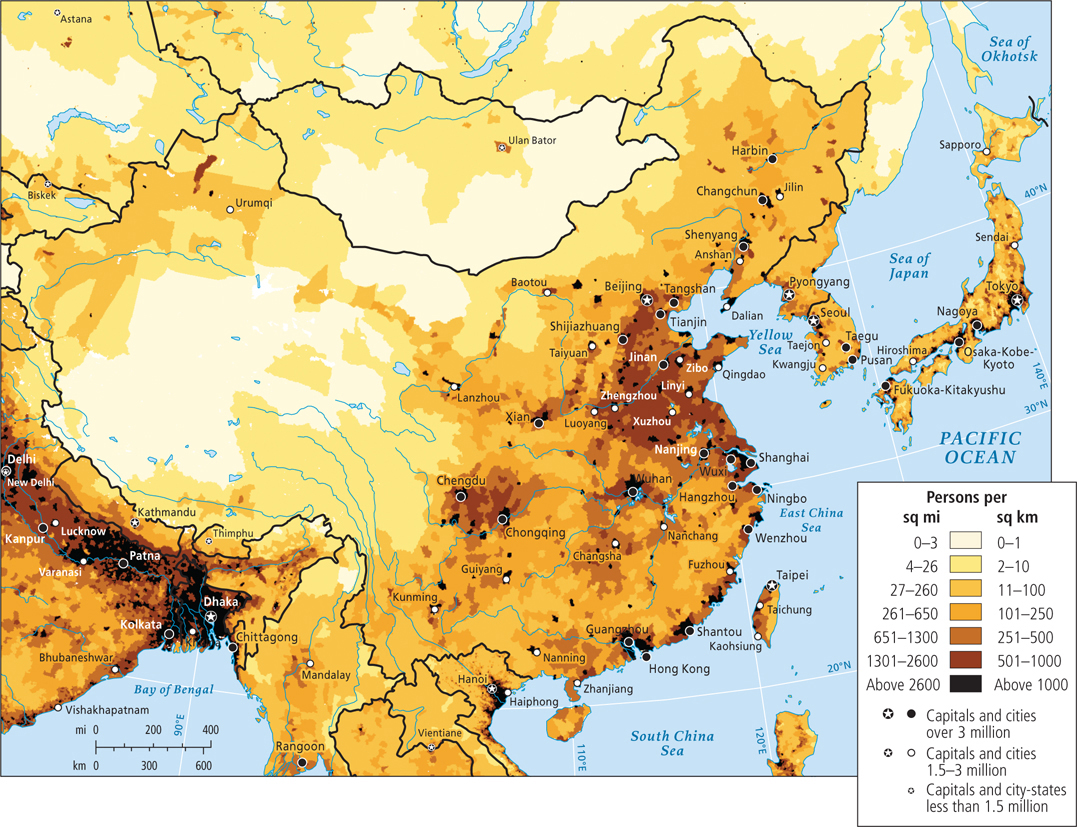

In East Asia, people are not evenly distributed across the land (Figure 9.25). China, with 1.35 billion people, has more than one-

The west and south of the Korean Peninsula are also densely settled, as are northern and western Taiwan. In Japan, settlement is concentrated in a band that stretches from the cities of Tokyo and Yokohama on the island of Honshu, south through the coastal zones of the Inland Sea to the islands of Shikoku and Kyushu. This urbanized region is one of the most extensive and heavily populated metropolitan zones in the world, accommodating 86 percent of Japan’s total population. The rest of Japan is mountainous and more lightly settled. Mongolia is only lightly settled, with one modest urban area.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

GEOGRAPHIC INSIGHT 5

Population and Gender Although East Asia remains the most populous world region, families here are having far fewer children than in the past, resulting in populations that are aging. Meanwhile, the legacy of China’s now largely abandoned “one child” policy, combined with an enduring cultural preference in China for male children, has created a shortage of females.

The Japanese have the world’s longest life expectancy, at 83 years, and the world’s oldest population—

24 percent of Japanese people are over the age of 65. By 2055, this age group is projected to account for 40 percent of the population. China faces a crisis in elder care for two reasons: the high rate of rural-

to- urban migration and the shrinkage of family support systems because of the legacy of the one- child policy. Research suggests that at least 10 percent of young Chinese men will fail to find a mate; and poor, rural, uneducated men will have the most difficulty.