10.2 PHYSICAL GEOGRAPHY AND ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES

PHYSICAL PATTERNS

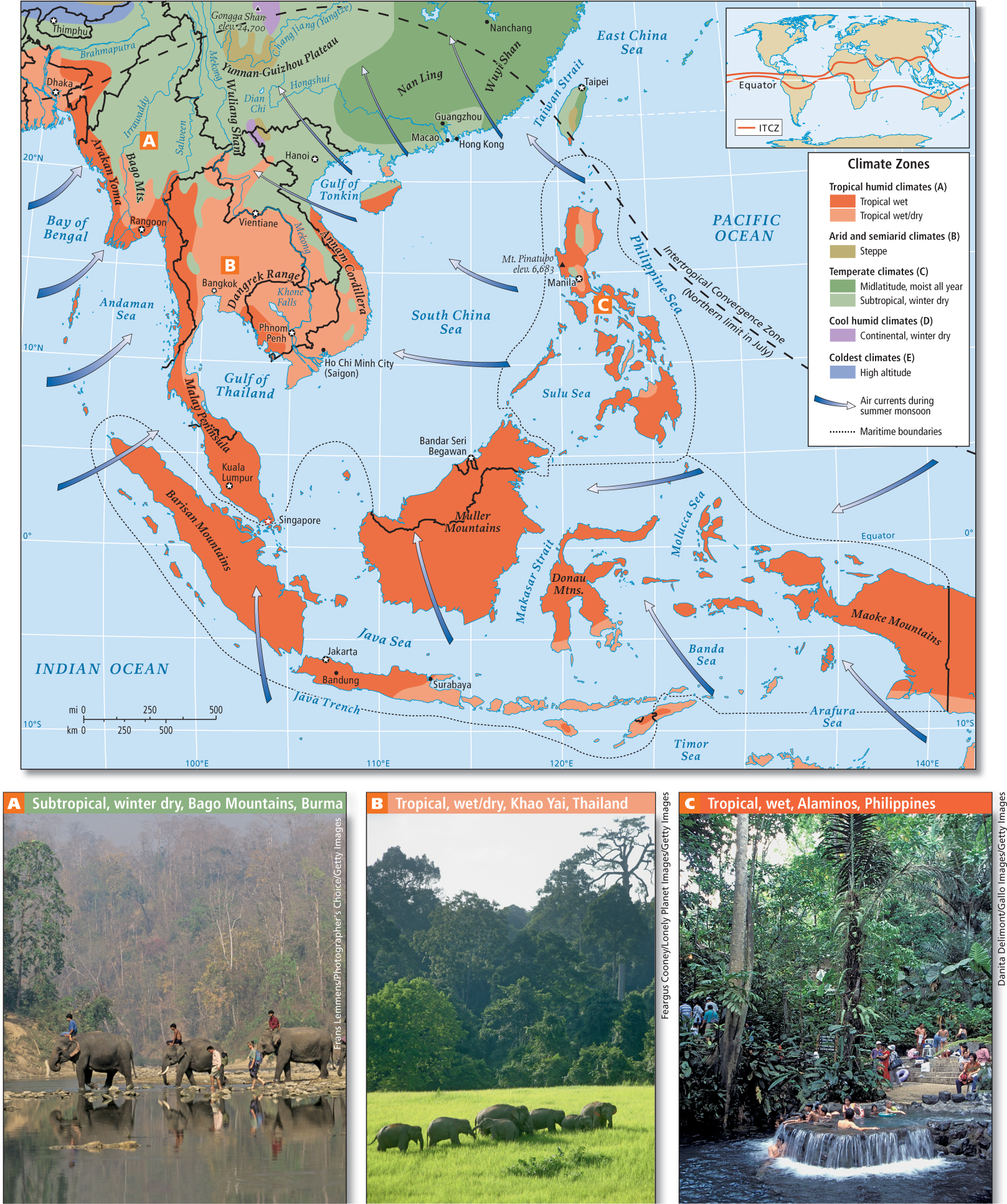

The physical patterns of Southeast Asia have a continuity that is not immediately obvious on a map. A map of the region shows a unified mainland region that is part of the Eurasian continent and a vast and complex series of islands arranged in chains and groups. These landforms are actually related in tectonic origin. Climate is another source of continuity; most of the region is tropical or subtropical.

Landforms

Southeast Asia is a region of peninsulas and islands (see Figure 10.1). Although the region stretches over an area larger than the continental United States, most of that space is ocean; the area of all the region’s landmass amounts to less than half that of the contiguous United States. Burma, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam occupy the large Indochina peninsula that extends south of China. This peninsula itself sprouts the long, thin Malay Peninsula that is shared by outlying parts of Burma and Thailand, a main part of Malaysia, and the city-

archipelago a group, often a chain, of islands

The irregular shapes and landforms of the Southeast Asian mainland and archipelago are the result of the same tectonic forces that were unleashed when India split off from the African Plate and gradually collided with Eurasia (see Figure 1.8). As a result of this collision, which is still underway, the mountainous folds of the Plateau of Tibet reach heights of almost 20,000 feet (6100 meters). These folded landforms, which bend out of the high plateau, turn south into Southeast Asia. There, they descend rapidly and then fan out to become the Indochina peninsula. Deep gorges widen out into valleys that stretch toward the sea, each containing hills of 2000 to 3000 feet (600 to 900 meters) and a river or two flowing from the mountains of the Yunnan–

The curve formed by Sumatra, Java, the Lesser Sunda Islands (from Bali to Timor), and New Guinea conforms approximately to the shape of the Eurasian Plate’s leading southern edge (see Figure 1.8). Where the Indian-

Volcanic eruptions and the mudflows and landslides that follow eruptions complicate and endanger the lives of many Southeast Asians. Earthquakes are especially problematic because of the tsunamis they can set off (see Figure 10.1E). The tsunami of December 2004, triggered by a giant earthquake (9.1 in magnitude) just north of Sumatra, swept east and west across the Indian Ocean, taking the lives of 230,000 people (170,000 in Aceh Province, Sumatra) and injuring many more. It was one of the deadliest natural disasters in recorded history. There has been a series of strong earthquakes since, with several along coastal Sumatra in August and September of 2009, April and May 2010, and April of 2012; but they did not generate notable tsunamis. Over the long run, the volcanic material creates new land and provides minerals that enrich the soil for farming.

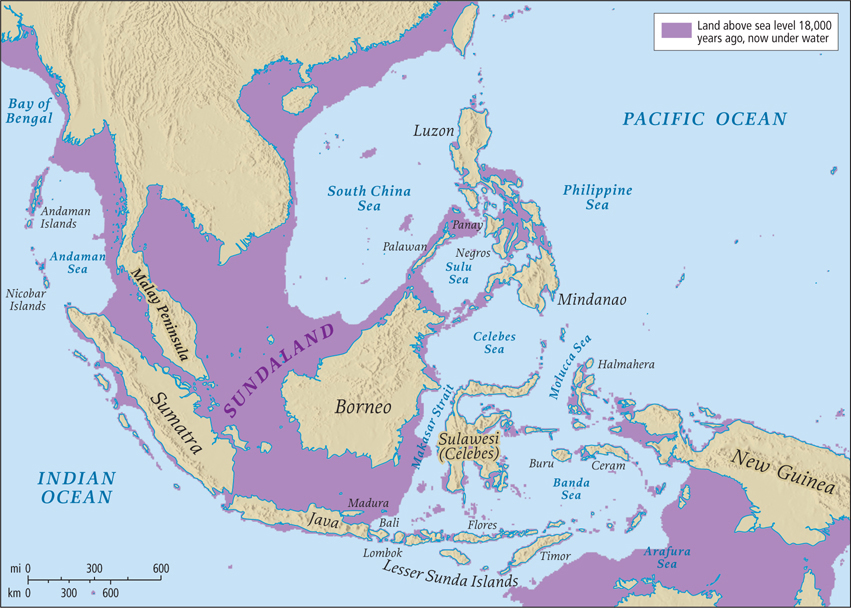

The now-

Climate and Vegetation

The largely tropical climate of Southeast Asia is distinguished by continuous warm temperatures in the lowlands—

Irregularly every 2 to 7 years, the normal patterns of rainfall are interrupted, especially in the islands, by the El Niño phenomenon (see Figure 11.6). In an El Niño event, the usual patterns of air and water circulation in the Pacific are reversed. Ocean temperatures are cooler than usual in the western Pacific near Southeast Asia. Instead of warm, wet air rising and condensing as rainfall, cool, dry air sits on the ocean surface. The result is severe drought, often with catastrophic effects for farmers and for tinder-

The soils in Southeast Asia are typical of the tropics. Although not particularly fertile, they will support dense and prolific vegetation when left undisturbed for long periods. The warm temperatures and damp conditions promote the rapid decay of detritus (dead organic material) and the quick release of useful minerals. These minerals are taken up directly by the roots of the living forest rather than enriching the soil. Because rainfall is usually abundant during the summer wet season (when drought is only episodic), this region has some of the world’s most impressive forests in both tropical and subtropical zones (see Figure 10.7). On the mainland, human interference, coupled with the long winter dry season, has reduced the forest cover. The relationships between humans and the environment that affect forests elsewhere in the region are discussed in the opening vignette and in the next section.

detritus dead organic material (such as plants and insects) that collects on the ground

THINGS TO REMEMBER

The irregular shapes and landforms of the Southeast Asian mainland and archipelago are the result of the same tectonic forces that were unleashed when India split off from the African Plate and crashed into Eurasia.

Continuous warm temperatures in the lowlands and heavy rain distinguish the tropical climate of Southeast Asia, except during those irregular years of the El Niño phenomenon.