10.6 POWER AND POLITICS

GEOGRAPHIC INSIGHT 3

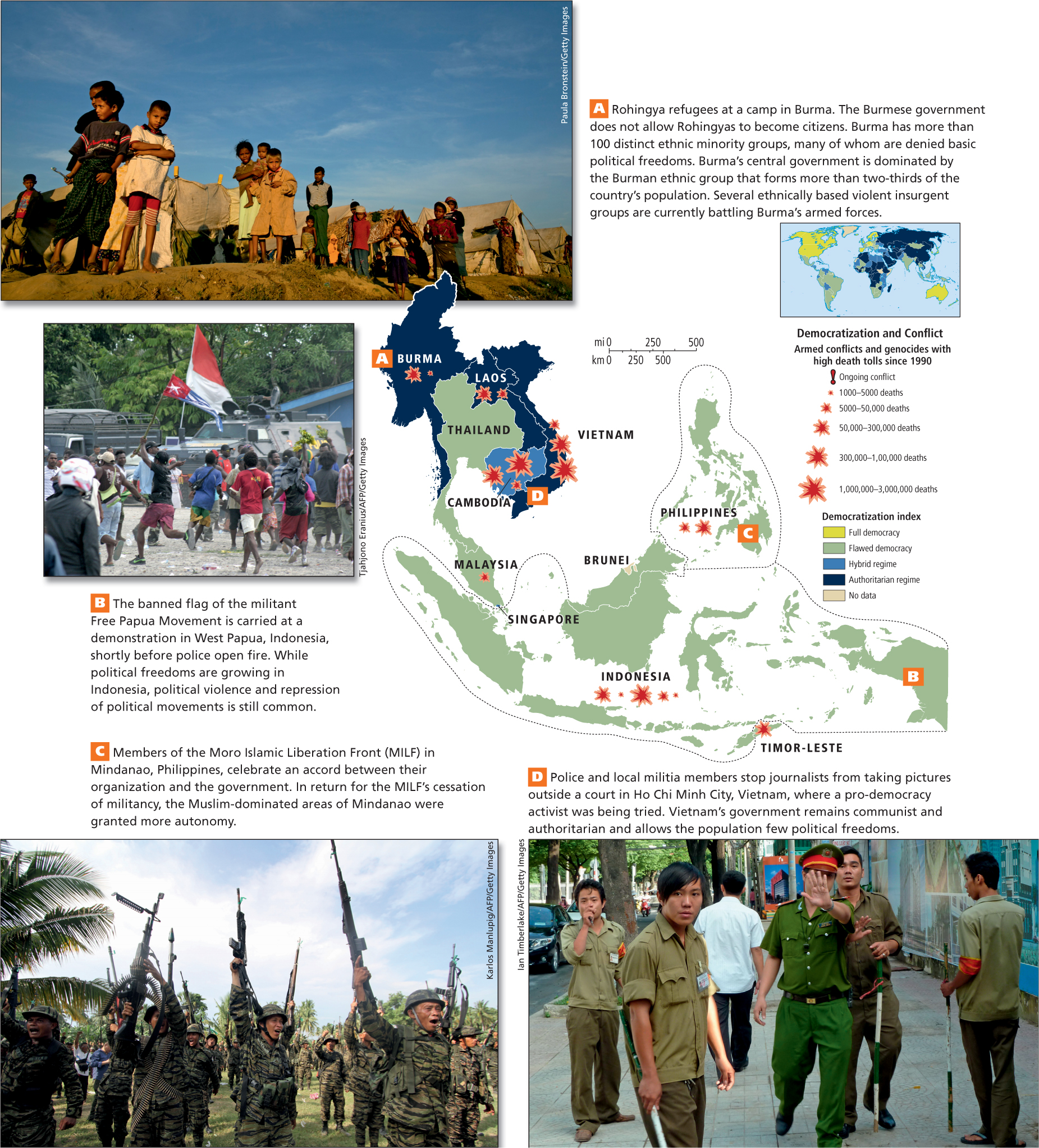

Power and Politics: There has been a general expansion of political freedoms throughout Southeast Asia in recent decades, but authoritarianism, corruption, and violence have at times reversed these gains.

While there is a general shift away from authoritarianism and toward more political freedoms, the Figure 10.18 map shows the wide variation in political freedoms in the region. Some people argue that authoritarianism has deep cultural roots in Southeast Asia and should be given greater respect. Others see a certain amount of authoritarianism as necessary to control corruption and political violence. Still others argue that respect for political freedoms is more likely to expose corruption and transform militant movements into peaceful political parties.

THINKING GEOGRAPHICALLY

Use the Photo Essay above to answer these questions.

Question 10.15

A What details in this picture are clues that these people are refugees?

Question 10.16

B Why would a government ban a flag?

Question 10.17

C What does this picture suggest about the MILF?

Southeast Asia’s Authoritarian Tendencies

Some Southeast Asian leaders, such as Singapore’s former prime minister, Lee Kuan Yew, have said that Asian values are not compatible with Western ideas of democracy and political freedom. Yew asserts that Asian values are grounded in the Confucian view that individuals should be submissive to authority; therefore Asian countries should avoid the highly contentious public debate of open electoral politics. Nevertheless, when confronted with governments that abuse their power, people throughout Southeast Asia have not submitted but rebelled (see Figure 10.18A, B). Even in Singapore, the Western-

While authoritarianism seems to be giving way to more political freedom, this process is often complicated by corruption and violent state repression of political movements. For example, after being plagued with a long line of dictators, the Philippines has now elected governments that have resolved some significant problems. However, militants in the southern islands continue an insurgency that periodically devolves into violence (see Figure 10.18C).

Thailand, long regarded as the most stable democracy in the region, is now dealing with deep divisions between those who favor authoritarianism (including many among the economic elite and the military) and those who are part of or support the large populist political movement. In 2006, the military took over Thailand’s government after a corrupt but charismatic prime minister, Thaksin Shinawatra, was implicated in several scandals. Despite recent elections, the matter remains unresolved. Shinawatra is in exile in Europe and his many supporters periodically take over the streets of Bangkok. In 2011, Shinawatra’s sister, Yingluck, was elected prime minister, with overwhelming support from her brother’s supporters. In 2014, she was removed from power by Thailand’s Constitutional Court, after which the military seized control of the government.

Other countries are also struggling to find a balance between meeting demands for more political freedoms and relying on authoritarianism to create stability. Cambodia’s democracy is precarious, and violence there is common. The wealthier and usually stable countries of Malaysia and Singapore continue to use authoritarian versions of democracy that impose severe limitations on freedom of the press and freedom of speech.

When more democratically oriented governments fail to keep the peace, authoritarianism, often backed by a strong military, is seen as a justified counterforce to “too much” democracy. In virtually every country, the military has been called on to restore civil calm after periods of civil disorder. Military rank is highly regarded and many top elected officials have had military careers.

Authoritarian rule remains firmly entrenched in some countries such as Burma where numerous regional ethnic minorities and pro-

Little political reform is occurring in Laos and Vietnam (see Figure 10.18D), where authoritarian socialist regimes have a firm grip on power, or in Brunei, which is governed by an authoritarian sultanate. For these and other reasons, authoritarianism is likely to remain a powerful force in the politics of this region for some time.

Militarism and China

While the countries of the region are unlikely to go to war against each other, they are keeping an eye on China, given its recent interest in the South China Sea. Newly discovered oil resources there, as well as fishing resources and vital shipping routes, have resulted in competing territorial claims by China, Taiwan, Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei, Indonesia, and the Philippines. Most countries have recently invested heavily in military equipment, primarily from Europe and the United States. In the midst of this buildup, countries with no claims on the South China Sea are arming themselves. In recent years, tiny, wealthy, trade-

Can the Expansion of Political Freedoms Help Bring Peace to Indonesia?

All Southeast Asian countries have diverse multicultural populations that at times come into conflict with each other. Efforts to resolve differences take many forms, both peaceful and violent. Much attention is now focused on Indonesia as it works to find peaceful political solutions to ethnic conflicts.

An important but still tentative shift toward democracy took place in Indonesia in the wake of the economic crisis of the late 1990s. After three decades of semi-

Indonesia is the largest country in Southeast Asia and the most fragmented—

Until the end of World War II, Indonesia was a loose assembly of distinct island cultures that Dutch colonists managed to hold together as the Dutch East Indies. When Indonesia became an independent country in 1945, its first president, Sukarno, hoped to forge a new nation out of these many parts, founded on a fairly strong communist ideology. To that end, he articulated a national philosophy known as Pancasila, which was aimed at holding the disparate nation together, primarily through nationalism and concepts of religious tolerance.

In 1965, during the height of the Cold War, Suharto, a staunchly anti-

Despite his abrupt removal from office, Sukarno’s unifying idea of Pancasila endures as a central theme of life in Indonesia (and less formally throughout the region). Pancasila embraces five precepts: belief in God, and the observance of conformity, corporatism (often defined as “organic social solidarity with the state”), consensus, and harmony. These last four precepts could be interpreted as discouraging dissent or even loyal opposition, and they seem to require a perpetual stance of boosterism. Pancasila has been criticized by some Indonesians as being too secular, while others see it as not going far enough to protect the freedom of people to believe in multiple deities, as Indonesia’s many Hindus do, or freedom to not believe in any deity at all. Some praise Pancasila’s other precepts for counteracting the extreme ethnic diversity and geographic dispersion of the country, while others say that the precepts have had a chilling effect on participatory democracy and on criticism of the government, the president, and the army.

The first orderly democratic change of government in Indonesia did not take place until national elections in 2004. Since then, there have been several peaceful elections, and the government is stable enough to allow citizens to publicly protest some policies. But corruption remains a threat that encourages feelings of nostalgia for the Suharto model of authoritarian government.

Separatist movements have sprouted in four distinct areas in recent years, demonstrating Indonesia’s fragility. The only rebellion to succeed was in Timor-

resettlement schemes government plans to move large numbers of people from one part of a country to another to relieve urban congestion, disperse political dissidents, or accomplish other social purposes; also called transmigration

The far-

Terrorism, Politics, and Economic Issues Like authoritarianism, terrorism has been a counterforce to political freedoms in this region. Terrorist violence short-

THINGS TO REMEMBER

GEOGRAPHIC INSIGHT 3

Power and Politics There has been a general expansion of political freedoms throughout Southeast Asia in recent decades, but authoritarianism, corruption, and violence have at times reversed these gains.

Some Southeast Asian leaders, such as Singapore’s former prime minister, Lee Kuan Yew, have said that Asian values are not compatible with Western ideas of democracy and political freedom.

While the countries of the region are unlikely to go to war against each other, they are keeping an eye on China, given its recent interest in the South China Sea.

All Southeast Asian countries have diverse multicultural populations that at times come into conflict with each other.

Like authoritarianism, terrorism has been a counterforce to political freedoms in this region.

225. TERROR AND ISLAMIC STRUGGLE IN INDONESIA

225. TERROR AND ISLAMIC STRUGGLE IN INDONESIA