10.8 POPULATION AND GENDER

GEOGRAPHIC INSIGHT 5

Population and Gender: Population dynamics vary considerably in this region because of differences in economic development, government policies, prescribed gender roles, and religious and cultural practices. With regard to gender, economic change has brought better job opportunities and increased status for women, who then often choose to have fewer children. Some countries also have gender imbalances because of a cultural preference for male children.

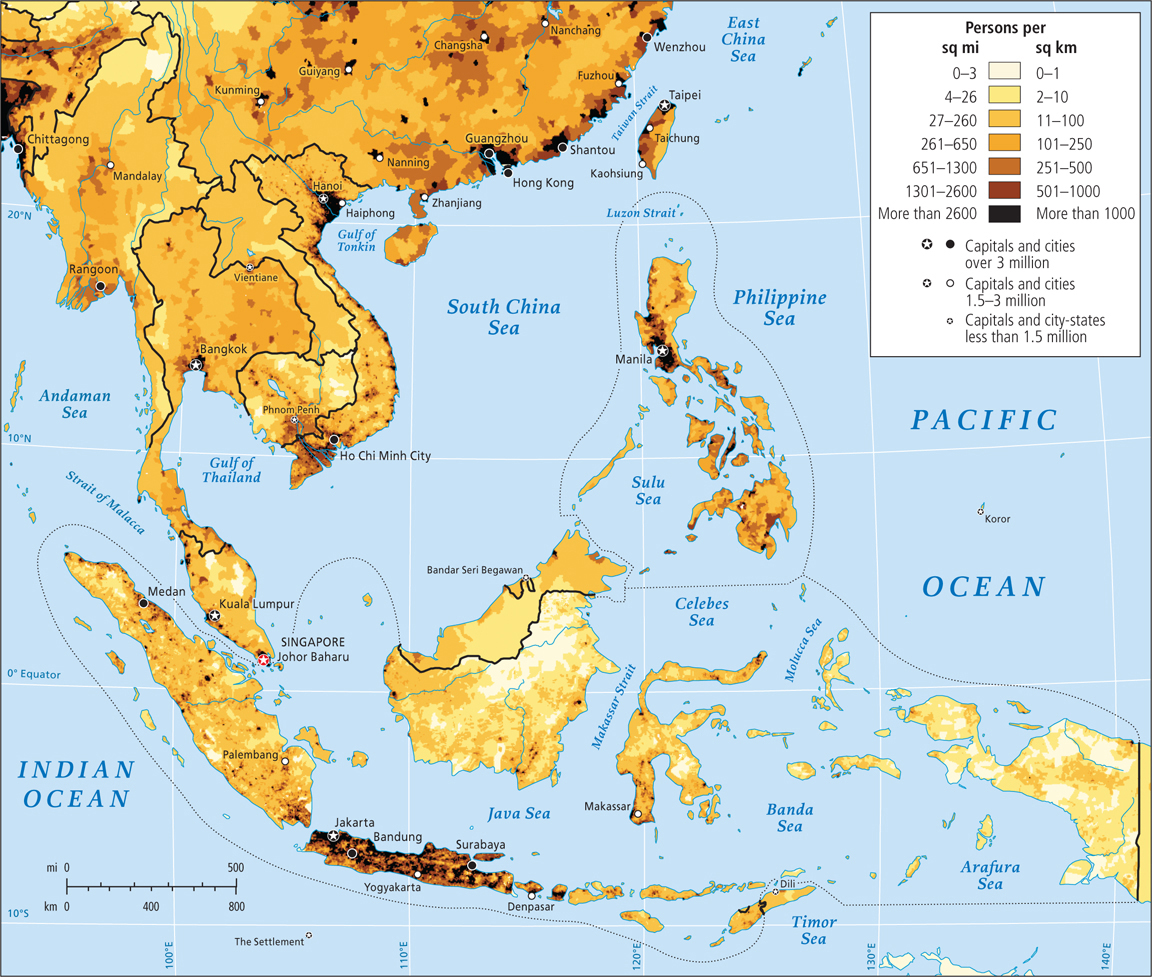

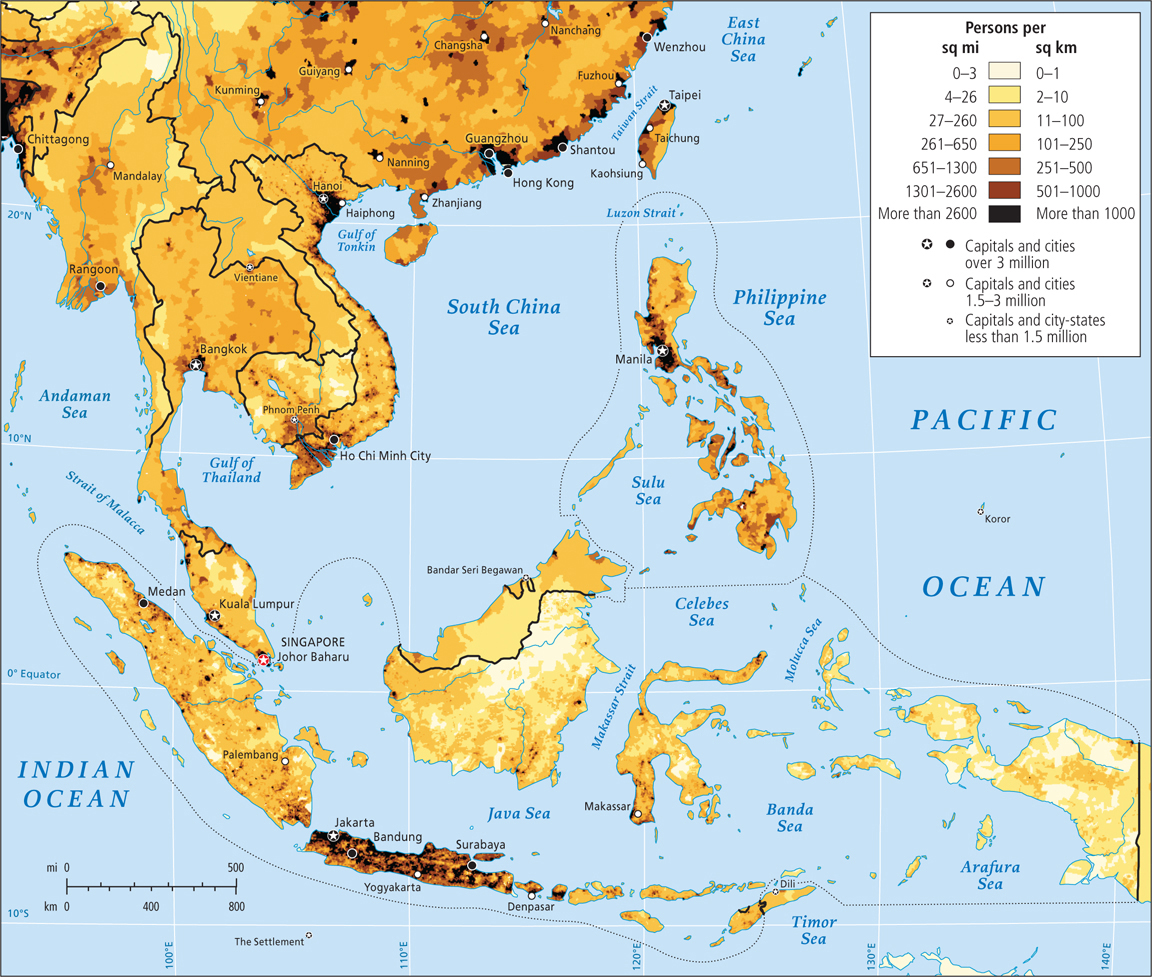

Southeast Asia is home to well over 600 million people (almost double the U.S. population), who occupy a land area that is about one-half the size of the United States. At current rates, Southeast Asia’s population, which is large and growing, is projected to reach more than 800 million by 2050, by which time much of this population will live in cities (Figure 10.21). However, population projections could be inaccurate, both because rates of natural increase are continuing to slow markedly and because many Southeast Asians are migrating to find employment outside the region.

Figure 10.21: Population density in Southeast Asia. Population growth in Southeast Asia is slowing, largely related to economic development, urbanization, changing gender roles, and government policies. Fertility rates have declined sharply in all countries since the 1960s but are still high in the poorest areas.

Page 436

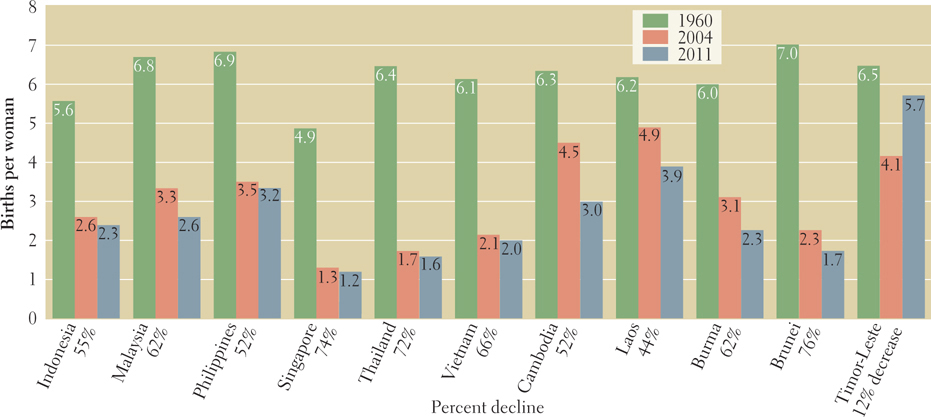

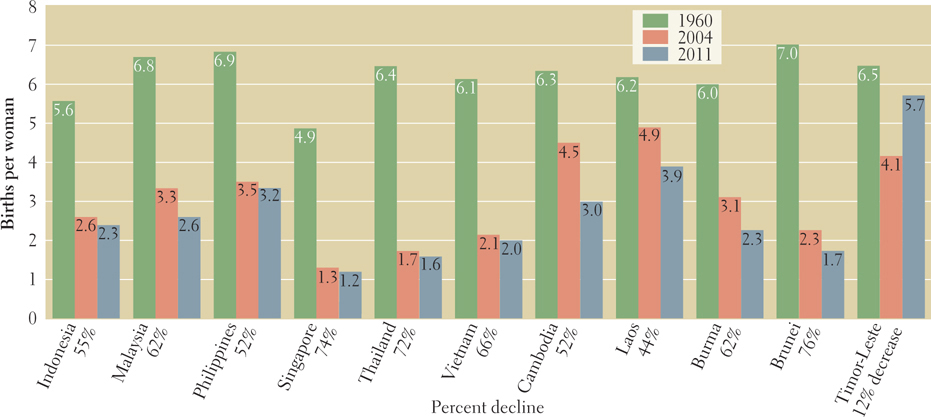

Population Dynamics Population dynamics vary considerably among the countries of Southeast Asia. The variation is due in part to differences in economic development, government policy, prescribed gender roles, and broader religious and cultural practices. Most countries are nearing the last stage of the demographic transition, where births and deaths are low and growth is minuscule or slightly negative. In the last several decades, overall fertility rates in Southeast Asia have dropped rapidly (Figure 10.22). Whereas women formerly had 5 to 7 children, they now have 1 to 3, with Laos (3.9) and Timor-Leste (5.7) being the major exceptions. However, because in most countries populations are still quite young (between one-quarter and one-third of the people are aged 15 years or younger), modest population growth is likely for several decades because so many are just coming into their reproductive years.

Figure 10.22: Total fertility rates, 1960, 2004, and 2011. Total fertility rates declined for all Southeast Asian countries from 1960 to 2011, but they did increase in Timor-Leste between 2004 and 2011.

[Sources consulted: Sasha Loffredo, A Demographic Portrait of South and Southeast Asia (Washington, DC: Population Reference Bureau, 1994), p.39; 2009 World Population Data Sheet (Washington, DC: Population Reference Bureau, 2009)]

Brunei, Singapore, and Thailand have reduced their fertility rates so sharply—below replacement levels—that they will soon need to cope with aging and shrinking populations. Regionally, education levels are the highest in Singapore, where most educated women work outside the home at skilled jobs and professions. The Singapore government is now so concerned about the low fertility rate that it offers young couples various incentives for marrying and procreating.

An important source of population growth for Singapore is the steady stream of highly skilled immigrants that its vibrant economy attracts. Many of these immigrants come from elsewhere in the region, though the country also draws highly skilled workers from the United States and Europe. Singapore also attracts immigrants from elsewhere in Southeast Asia, primarily in the building trades and low-wage services. All countries in this region are losing population to emigration, with the exceptions of Singapore, Malaysia, and Brunei.

Thailand’s low fertility rate of 1.6 children per adult woman was achieved in part via a government-sponsored condom campaign, and in part by rapid economic development, which made many couples feel that smaller families would be best. Also, as women gained more opportunities to work and study outside the home, they decided to have fewer children. High literacy rates for both men and women, along with Buddhist attitudes that accept the use of contraception, have also been credited for the decline in Thailand’s fertility rate.

The poorest and most rural countries in the region show the usual correlation between poverty, high fertility, and infant mortality. Timor-Leste, which suffered a violent, impoverishing civil disturbance before it became independent from Indonesia, is still characterized by poverty, high fertility, and high infant mortality (64 per 1000 live births). However, its oil resources promise to bring prosperity if those resources are used to help the welfare of the entire population. If that happens, both fertility and infant mortality can be expected to fall.

In Cambodia and Laos, fertility rates average 3.0 and 3.9 children, respectively. Infant mortality rates are 58 per 1000 live births for both Cambodia and Laos. On the other hand, in Vietnam, where people are only slightly more prosperous and urbanized, the fertility rate (2.0 children per adult woman) and infant mortality rate (16 per 1000 births) are far lower. These lower rates are explained by the fact that as a socialist state, Vietnam provides basic education and health care—including birth control—to all, regardless of income. In Vietnam, literacy rates are more than 96 percent for men and 92 percent for women, whereas they are only 64 percent for women in Cambodia and in Laos. In addition, Vietnam’s rapidly developing economy is pulling in foreign investment, which provides more employment for women, and careers are replacing child rearing as the central focus of many women’s lives.

Out of concern that these changes weren’t happening rapidly enough, and that a rapidly growing population would jeopardize Vietnam’s upswing in economic development, the government of Vietnam recently reintroduced a two-child family policy that it has had on and off since the 1960s. This policy has already brought on gender imbalance, as some couples are choosing abortion if the fetus is female.

Page 437

The Philippines, which has a higher per capita income than Laos, Cambodia, Timor-Leste, or Vietnam, is an anomaly in population patterns, primarily because it is predominantly Roman Catholic (83 percent, see the Figure 10.25 map), a religion that officially does not allow birth control. Fertility there is among the highest in the region (3.2 per adult female); infant mortality is in the medium range (22 per 1000 live births); and maternal childbirth deaths are high despite female literacy rates also being high (93 percent).

VIGNETTE

In the Roman Catholic Philippines, Gina Judilla, who works outside the home, has had six children with her unemployed husband. They wanted only two, but because of the strong role of the Catholic Church and the political pressure it exerts, birth control was not available to them. Abortion is legal only to save the life of the mother, so with every succeeding pregnancy she tried folk methods of inducing an abortion. None worked. Now she can afford to send only two of her six children to school.

A move by family planners to provide national reproductive health services and sex education is underway. A recent survey showed that 48 percent of all pregnancies in the Philippines in 2010 were unintended, which often led to illegal “backstreet” abortions. In 2011, only one-third of Philippine women had access to modern birth control methods. [Source: Likhaan Center for Women’s Health, Inc., and the New York Times. For detailed source information, see Text Sources and Credits.]

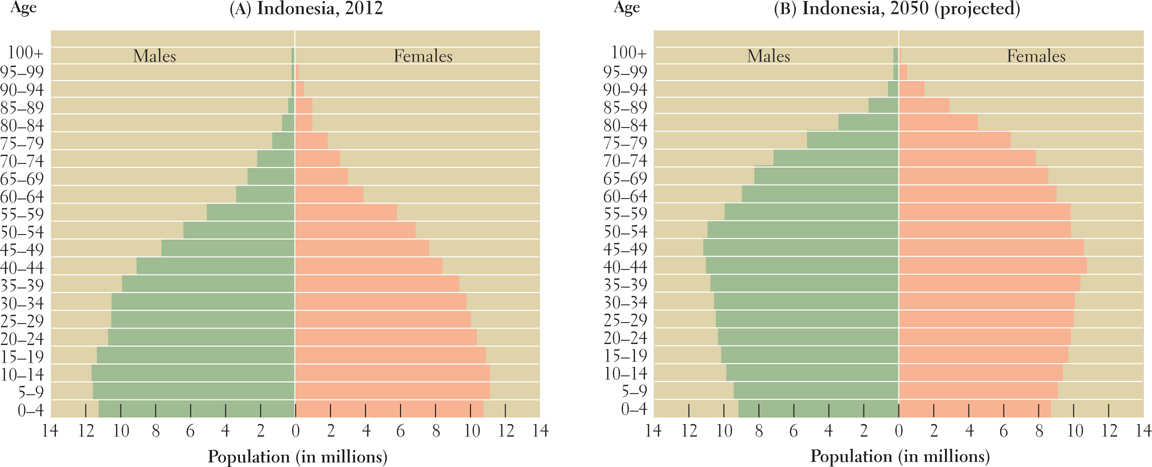

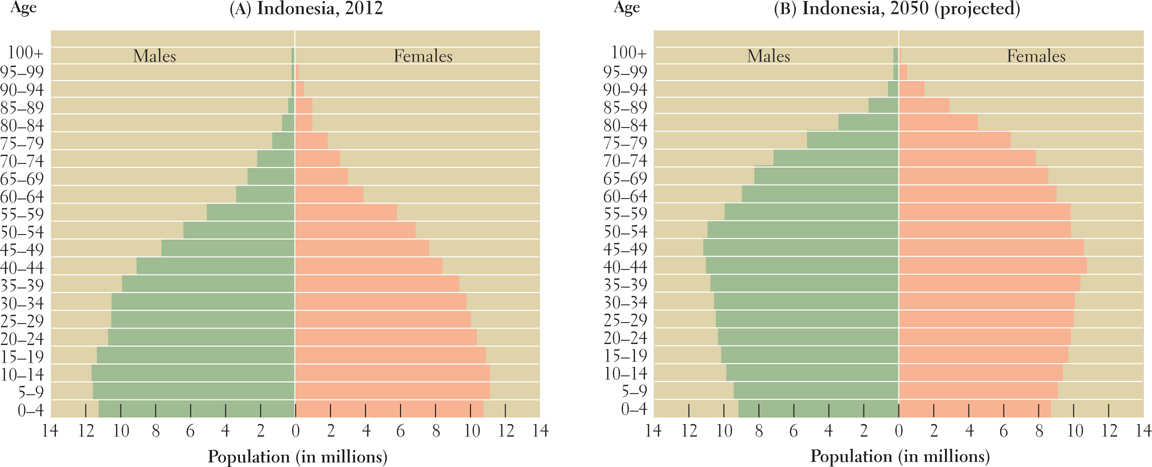

Population Pyramids The youth and gender features of Southeast Asian populations are best appreciated by looking at the population pyramids for Indonesia. Figure 10.23 shows the 2012 population and the projected population for 2050. The wide bottom of the 2012 pyramid indicates that most people are age 30 and under, but the projections to 2050 show that eventually, with declining birth rates, those 30 and under will be outnumbered by those 35 and older. Indonesia will accumulate ever-larger numbers in the upper age groups, and the pyramid will eventually be more box-shaped, as those for Europe are now. The gender disparities (more males than females) that have developed over the last 20 years can be seen by carefully examining the length of the bars on the male and female sides of the pyramid for those aged 15–19 and under. The difference is slight but significant because there is a rather consistent deficit of females, which indicates that they were selected out before birth, as is the case in Vietnam.

Figure 10.23: Population pyramids for Indonesia, 2012 and 2050 (projected). In 2012, Indonesia’s population was 248.2 million. It is projected to be 313 million in 2050.

Southeast Asia’s Encounter with HIV-AIDS As in sub-Saharan Africa (see Chapter 7), HIV-AIDS is a significant public health issue in Southeast Asia, although infection and death rates are now declining across the region. Cambodia, Thailand, and Burma currently have the highest infection rates.

Thailand is one of the few countries that has been able to drastically reduce the incidence of HIV-AIDS. It did so through a well-funded program that increased the use of condoms, decreased STDs dramatically, and reduced visits to sex workers by half. In Thailand in 2001, AIDS was the leading cause of death, overtaking stroke, heart disease, and cancer, but it is now just the third leading cause of death. Estimates are that about 500,000 Thais are infected, down from 1 million 12 years ago. Men between the ages of 20 and 40 have the highest rates of infection, but the rate of infection among women is rising.

Page 438

Elsewhere in the region, HIV rates are expected to increase rapidly in rural areas and in secondary cities where conservative religious leaders and faith-based international agencies restrict sex education and AIDS-prevention programs, such as the promotion of condom use. Sex education is viewed as promoting promiscuity. Aggressive prevention programs are even more essential because of popular customs that support sexual experimentation (at least among men), the reluctance of women to insist that their husbands and boyfriends use condoms, intravenous drug use (primarily by men), and the high mobility of young adults. Also contributing to the spread of HIV among young women are sex tourism and sex-related human trafficking (discussed further later in this chapter).  233. ACTIVISTS: AIDS LINKED TO WOMEN’S RIGHTS ABUSES

233. ACTIVISTS: AIDS LINKED TO WOMEN’S RIGHTS ABUSES

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Population and Gender Population dynamics vary considerably in this region because of differences in economic development, government policies, prescribed gender roles, and religious and cultural practices. With regard to gender, economic change has brought better job opportunities and increased status for women, who then often choose to have fewer children. Some countries also have gender imbalances because of a cultural preference for male children.

While population growth rates have slowed across the region, they are slowing the most in the developed economies of Singapore, Brunei, and Thailand.

An important source of population growth for Singapore is the steady stream of highly skilled immigrants that its vibrant economy attracts.

The variations in population growth are linked to relative prosperity, gender roles, and availability of birth control.

HIV-AIDS is a threat, to varying degrees, throughout the region. Preventative measures have proven quite successful in Thailand.

233. ACTIVISTS: AIDS LINKED TO WOMEN’S RIGHTS ABUSES

233. ACTIVISTS: AIDS LINKED TO WOMEN’S RIGHTS ABUSES