10.9 SOCIOCULTURAL ISSUES

Because of the region’s long and complex history, the people of Southeast Asia have a great diversity of cultures and religious traditions. Now globalization and urbanization are adding yet more diversity as new cultural influences come in from abroad and as urban women gain more independence and pursue careers outside the home.

Cultural and Religious Pluralism

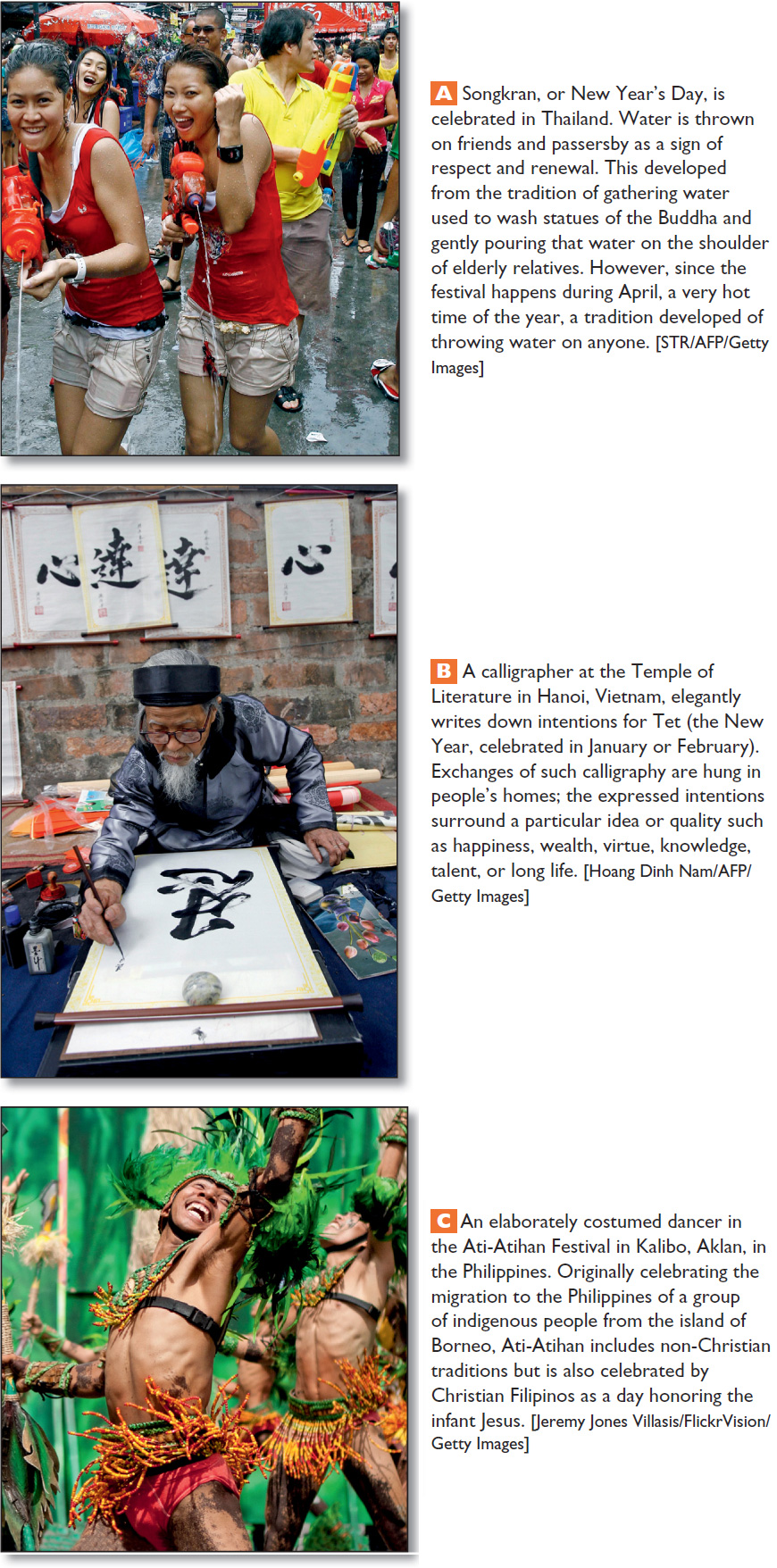

Southeast Asia is a place of cultural pluralism in that it is inhabited by groups of people from many different backgrounds. Over the past 40,000 years, migrants have come to the region from India, the Tibetan Plateau, the Himalayas, China, Southwest Asia, Japan, Korea, and the Pacific. Many of these groups have remained distinct, partly because they lived in isolated pockets separated by rugged topography or seas. However, the religious practices and traditions of many groups show diverse cultural influences (Figure 10.24).

cultural pluralism the cultural identity characteristic of a region where groups of people from many different backgrounds have lived together for a long time but have remained distinct

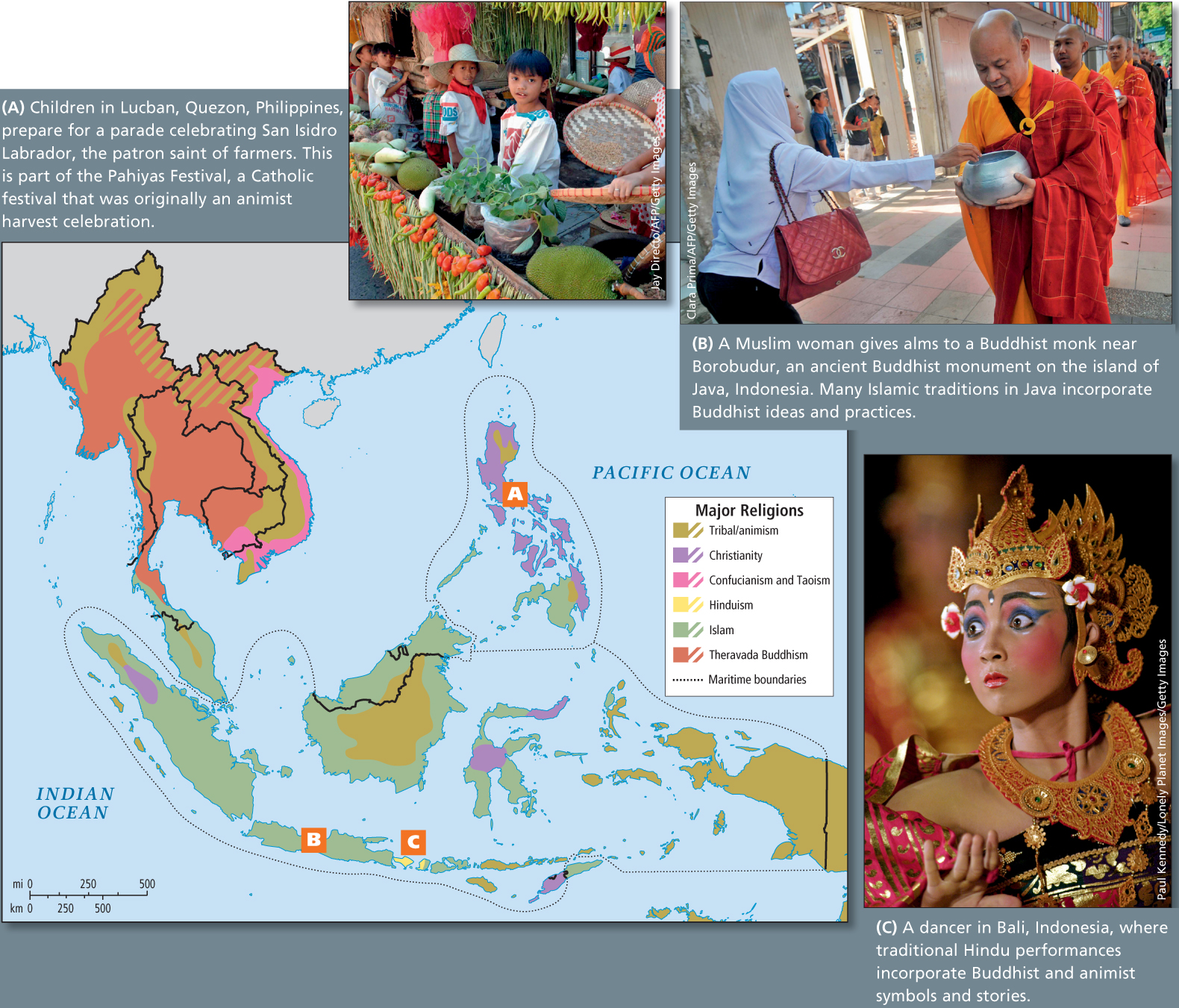

As discussed in the “Religious Legacies” section, the major religious traditions of Southeast Asia include Hinduism, Buddhism, Confucianism, Taoism, Islam, Christianity, and animism (Figure 10.25). In animism, a belief system common among many indigenous peoples, natural features such as rocks, trees, rivers, crop plants, and the rains all carry spiritual meaning. These natural phenomena are the focus of festivals and rituals to give thanks for bounty and to mark the passing of the seasons, and these ideas have permeated all the imported religious traditions of the region.

The patterns of religious practice are complex; the patterns of distribution reveal an island–

All of Southeast Asia’s religions have changed as a result of exposure to one another. Many Muslims and Christians believe in spirits and practice rituals that have their roots in animism. Hindus and Christians in Indonesia, surrounded as they are by Muslims, have absorbed ideas from Islam, such as the seclusion of women. Muslims have absorbed ideas and customs from indigenous belief systems, especially ideas about kinship and marriage, as illustrated in the vignette below.

VIGNETTE

Although arranged marriages have historically been the norm across Southeast Asia, in most urban and rural areas, marriages are now love matches. Such is the case for Harum and Adinda, who live in Tegal, on the island of Java in Indonesia. They met in high school and some 10 years later, after saving a considerable sum of money, decided to formally ask both sets of parents if they could marry. Harum, an accountant, would normally be expected to pay the wedding costs, which could run to many thousands of dollars; however, Adinda was able to contribute from her salary as a teacher. Like nearly all Javanese people, both are Muslim. Because Islam does not have elaborate marriage ceremonies, colorful rituals from Christianity, Buddhism, and indigenous animism will enhance the elaborate and festive occasion.

In preparation, both bride and groom participate in unique Javanese rituals that remain from the days when marriages were arranged and the bride and groom did not know each other (Figure 10.26). A pemaes, a woman who prepares a bride for her wedding and whose role is to inject mystery and romance into the marriage relationship, bathes and perfumes the bride. She also puts on the bride’s makeup and dresses her, all the while making offerings to the spirits of the bride’s ancestors and counseling her about how to behave as a wife and how to avoid being dominated by her husband. The groom also takes part in ceremonies meant to prepare him for marriage. Both are counseled that their relationship is bound to change over the course of the decades as they mature and as their family grows older.

Despite the elaborate preparations for marriage, divorce in Indonesia (and also in Malaysia) is fairly common among Muslims, who often go through one or two marriages early in life before they settle into a stable relationship. Although the prevalence of divorce is lamented by society, it is not considered outrageous or disgraceful. Apparently, ancient indigenous customs predating Islam allowed for mating flexibility early in life, and this attitude is still tacitly accepted. [Source: Jennifer W. Nourse and Walter Williams. For detailed source information, see Text Sources and Credits.]

Globalization Brings Cultural Diversity and Homogeneity Southeast Asia’s cities are extraordinarily culturally diverse, a fact that is illustrated by their food customs (Figure 10.27). But in some ways, this diversity decreases as the many groups continue to be exposed to each other and to global culture. For example, Malaysian teens of many different ethnicities (Chinese, Tamil, Malay, Bangladeshi) spend much of their spare time following the same European soccer teams, playing the same video games, visiting the same shopping centers, eating the same fast food, and talking to each other in English. While rural areas retain more traditional influences—

One group that has brought cultural diversity to Southeast Asia is the Overseas (or ethnic) Chinese (see Chapter 9). Small groups of traders from southern and coastal China have been active in Southeast Asia for thousands of years; over the centuries, there has been a constant trickle of immigrants from China. The forebearers of most of today’s Overseas Chinese, however, began to arrive in large numbers during the nineteenth century, when the European colonizers needed labor for their plantations and mines. Later, those who fled China’s Communist Revolution after 1949 sought permanent homes in Southeast Asian trading centers. Today, more than 26 million Overseas Chinese live and work across Southeast Asia, primarily as shopkeepers and as small business owners. A few are wealthy financiers, and a significant number are still engaged in agricultural labor.

Chinese success at small-

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

LGBT Rights in Thailand and Vietnam

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people are discriminated against throughout the world, and Southeast Asia is no exception. Both Thailand and Vietnam, though, are considering giving more legal recognition to same-

In recent years, when low-

Gender Patterns in Southeast Asia

Gender roles are being transformed across Southeast Asia by urbanization and the changes it brings to family organization and employment. Here we look at some surprising traditional patterns of gender roles in extended families. Moving to the city shifts people away from extended families and toward the nuclear family. The gains that women have made in political empowerment, educational achievement, and paid employment have not erased gender disparities.

Family Organization, Traditional and Modern Throughout the region, it has been common for a newly married couple to reside with, or close to, the wife’s parents. Along with this custom is a range of behavioral rules that empower the woman in a marriage, despite some basic patriarchal attitudes. For example, a family is headed by the oldest living male, usually the wife’s father. When he dies, he passes on his wealth and power to the husband of his oldest daughter, not to his own son. (A son goes to live with his wife’s parents and inherits from them.) Hence, a husband may live for many years as a subordinate in his father-

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

Women’s Improving Status in Southeast Asia

Building on strong traditional roles at the family level, women now occupy prominent political roles in many countries, and their rising educational levels suggest that even in the most conservative countries, changes in gender roles will be significant. One result of the rising political status of women is that there is more focus on the abuse of women and girls in the sex industry.

Another traditional custom that empowers women is that women are often the family financial managers. Husbands turn over their pay to their wives, who then apportion the money to various household and family needs.

Urbanization and the shift to the nuclear family mean that young couples now frequently live apart from the extended family, an arrangement that takes the pressure to defer to his father-

Political and Economic Empowerment of Women Women have made some impressive gains in politics in Southeast Asia. Economically, they still earn less money than men and work less outside the home, but this will likely change if their level of education in relation to that of men continues to increase (see “On the Bright Side”).

Southeast Asia has had several prominent female leaders over the years, most of whom have risen to power in times of crisis as the leaders of movements opposing corrupt or undemocratic regimes. In the Philippines, Corazon Aquino, a member of a large and powerful family, became president in 1986 after leading the opposition to Ferdinand Marcos, whose 21-

In Indonesia, Megawati Sukarnoputri became president in 2001 after decades of leading the opposition to Suharto’s notoriously corrupt 31-

All of these women leaders were wives, daughters, or siblings of powerful male political leaders, which raises some questions of nepotism. However, family favoritism cannot account for several countries where the percentage of female national legislators is well above the world average of 18 percent: Timor-

Despite their increasing successes in politics and their acknowledged role in managing family money, women still lag well behind men in terms of economic well-

Globalization and Gender: The Sex Industry

Southeast Asia has become one of several global centers for the sex industry, supported in large part by international visitors willing to pay for sex. Sex tourism in Southeast Asia grew out of the sexual entertainment industry that served foreign military troops stationed in Asia during World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War. Now, primarily civilian men arrive from around the globe to live out their fantasies during a few weeks of vacation. The industry is found throughout the region but is most prominent in Thailand. In 2013, twenty-

sex tourism the sexual entertainment industry that serves primarily men who travel for the purpose of living out their fantasies during a few weeks of vacation

One result of the “success” of sex tourism is a high demand for sex workers, which has attracted organized crime. Estimates of the numbers of sex workers vary from 30,000 to more than a million in Thailand alone. Gangs often coerce girls and women into remaining in sex work once they have been forced into the trade. Demographers estimate that 20,000 to 30,000 Burmese girls taken against their will—

VIGNETTE

Twenty-

Watsanah was born in northern Thailand to an ethnic minority group made up of impoverished subsistence farmers. She married at 15 and had two children shortly thereafter. Several years later, her husband developed an opium addiction. She divorced him and left for Bangkok with her children. She found work at a factory that produced seatbelts for a nearby automobile plant. In 2008, Watsanah lost her job as the result of the global economic crisis. To feed her children, she became a sex worker.

Although the pay, between U.S.$400 and U.S.$800 a month, is much better than the U.S.$100 a month she earned in the factory, the work is dangerous and demeaning. Sex work, though widely practiced and generally accepted in Thailand, is illegal, and the women who do it are looked down on. As a result, Watsanah must live in constant fear of going to jail and losing her children. Moreover, she cannot always make her clients use condoms, which puts her at high risk of contracting AIDS and other sexually transmitted diseases. “I don’t want my children to grow up and learn that their mother is a prostitute,” says Watsanah. “That’s why I am studying. Maybe by the time they are old enough to know, I will have a respectable job.” [Source: Field notes of Alex Pulsipher and Debbi Hempel; Kaiser Family Foundation; BBC News. For detailed source information, see Text Sources and Credits.]

THINGS TO REMEMBER

The major religious traditions of Southeast Asia include Hinduism, Buddhism, Confucianism, Taoism, Islam, Christianity, and animism. All originated outside the region, with the exception of the animist belief systems.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people are discriminated against throughout Southeast Asia, but both Thailand and Vietnam are considering giving more legal recognition to same-

sex couples. Women have made some impressive gains in politics in Southeast Asia, but they still earn less money than men and work less outside the home.

Gender roles are being transformed across Southeast Asia by urbanization and the changes it brings to family organization and employment.

Some countries have become centers for the global sex industry, which puts many women at risk of violence and disease.