11.1 Chapter 11 OCEANIA: AUSTRALIA, NEW ZEALAND, AND THE PACIFIC

chapter 11

OCEANIA: AUSTRALIA, NEW ZEALAND, AND THE PACIFIC▶

GEOGRAPHIC INSIGHTS: OCEANIA

After you read this chapter, you will be able to discuss the following geographic insights as they relate to the five thematic concepts:

|

1. |

Environment: |

Oceania faces a host of environmental problems and public awareness of environmental issues is keen. Global climate change, primarily warming, has brought rising sea levels and increasingly variable rainfall. Other major threats to the region’s unique ecology have come from the introduction of many nonnative species and the expansion of herding, agriculture, fishing, and human settlements. |

|

2. |

Globalization and Development: |

Globalization, coupled with Oceania’s stronger focus on neighboring Asia (rather than on its long- |

|

3. |

Power and Politics: |

In recent decades, stark divisions have emerged in Oceania over definitions of democracy— |

|

4. |

Urbanization: |

Oceania is only lightly populated but it is highly urbanized. The shift from agricultural and resource- |

|

5. |

Population and Gender: |

In this largest but least populated world region, there are two main patterns relevant to population and gender. Australia, New Zealand, and Hawaii have older and more slowly growing populations, and relatively more opportunities for women. The Pacific islands and Papua New Guinea have much more rural, younger, and rapidly growing populations, with fewer opportunities for women. |

The Oceania Region

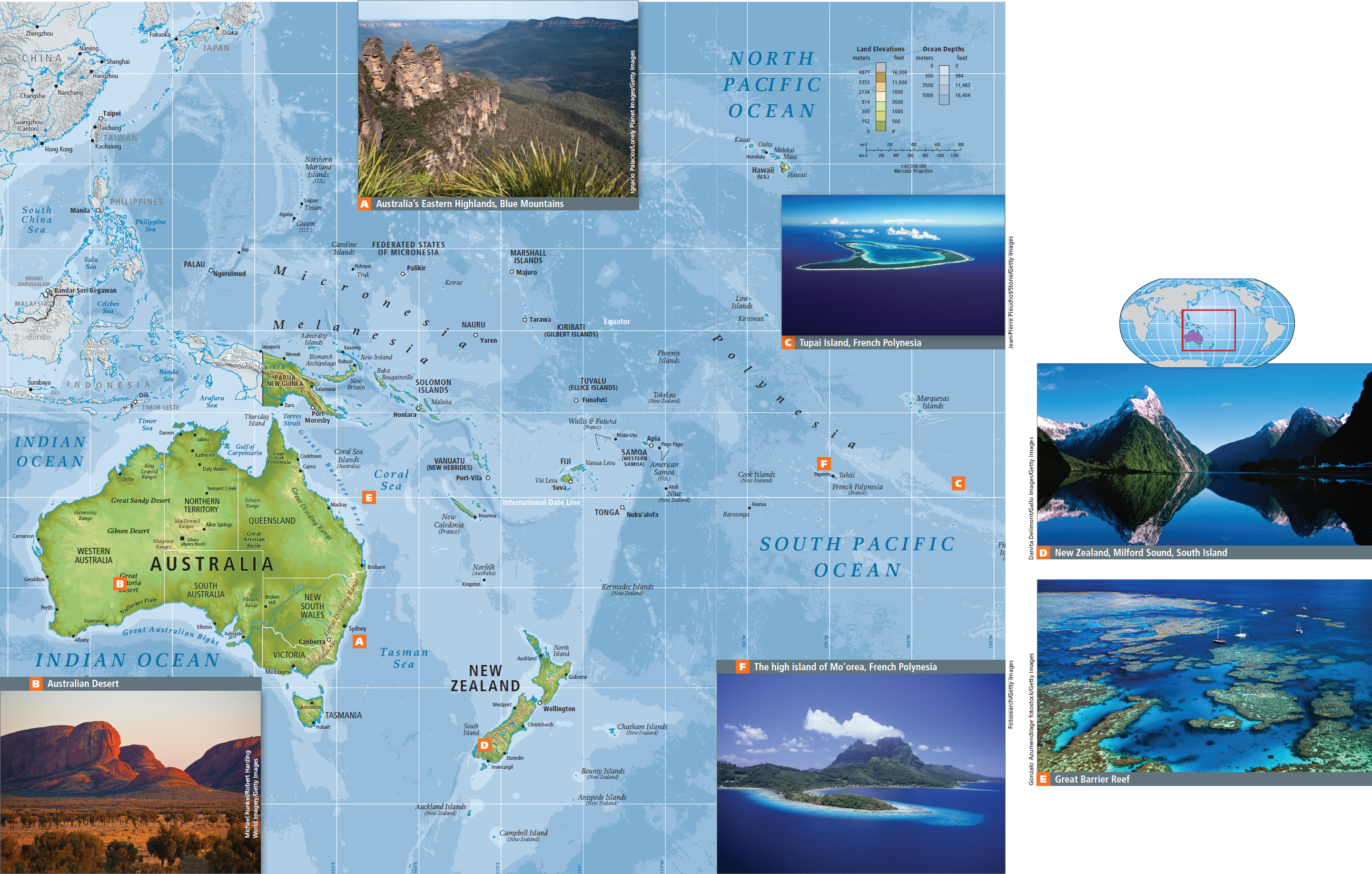

The region of Oceania, shown in Figure 11.1, is a vast and often idealized region that faces a number of difficult realities. The five thematic concepts in this book are explored as they arise in the discussion of these issues. Vignettes, like the one that follows about the Kiribati archipelago and the challenges its people face due to climate change, help illustrate the themes as they are experienced in individual lives.

GLOBAL PATTERNS, LOCAL LIVES

Aurora (a pseudonym) is a nursing student in Brisbane, Australia, who is undergoing a wrenching personal transition due to climate change. Aurora is from Kiribati, a Pacific nation of 33 tiny islands barely 6 and a half feet above sea level. Rising seas are swamping the Kiribati archipelago, which straddles the equator just west of the international date line (180° longitude). Aurora pines for her island’s blue lagoons. While she studies for a new future and prepares to become her household’s primary income earner, she does so without the daily close company of her raucous extended family.

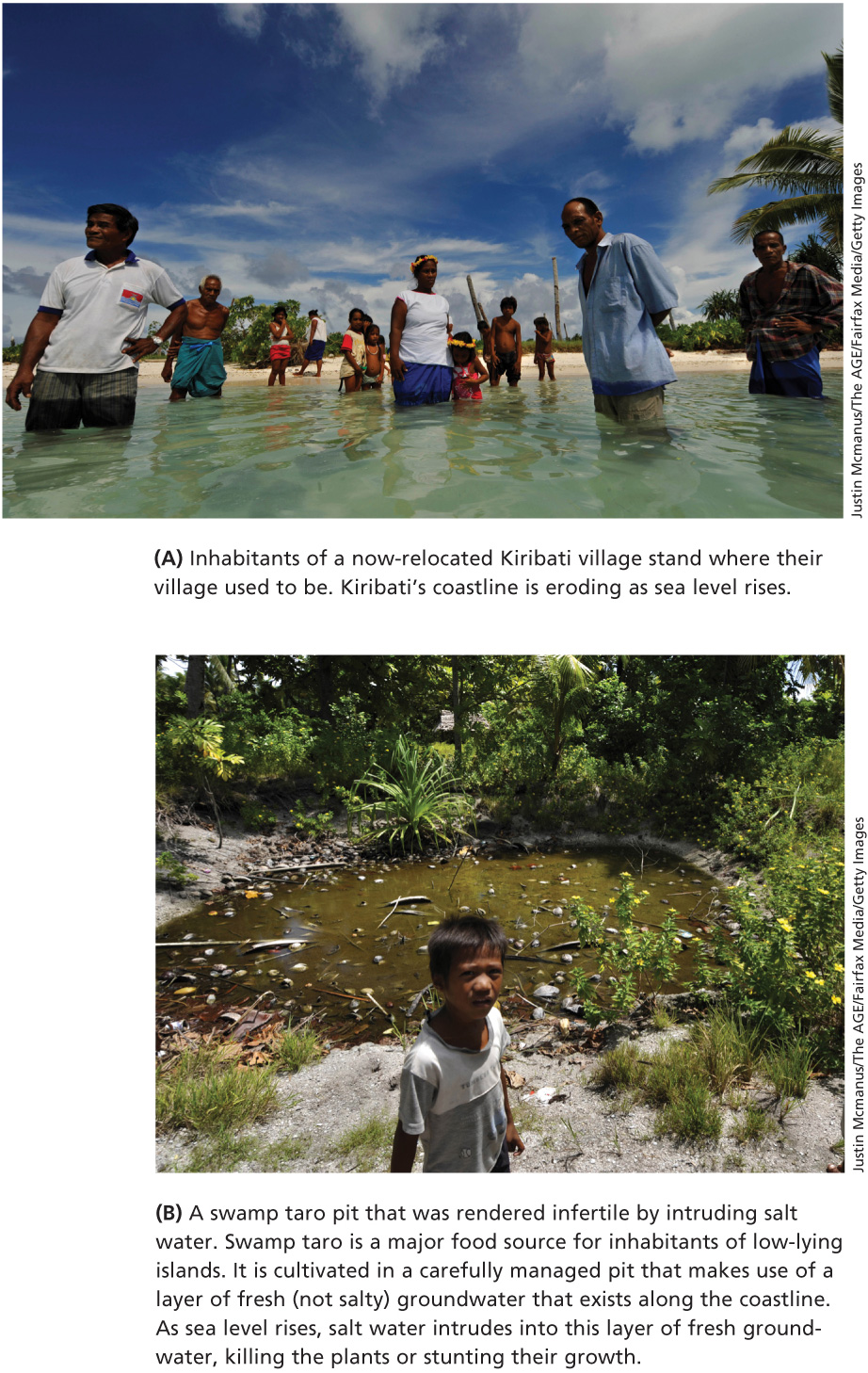

Several years ago, Aurora and her fellow citizens (100,000 people live in Kiribati) began to notice alarming environmental changes. Their drinking water was getting brackish (salty), several shoreline villages had sunk below sea level, and the climate had become so dry that skilled gardeners could no longer raise their customary cabbages, tomatoes, cucumbers, and swamp taro (Figure 11.2A, B). Drought conditions were being worsened by rising salty tides that saturated formerly fertile soil. Scientists predicted that, with rising seas and more frequent droughts and storms, much of Kiribati will be uninhabitable in a few decades.

Aurora’s nursing education, funded by a government program called AusAID, is one of several strategies developed by Kiribati president Anote Tong to encourage his people to gradually “migrate with dignity.” President Tong sees climate change as a huge challenge for his country, and he hopes that other South Pacific islands, as well as Australia and New Zealand, will allow Kiribati people to resettle there permanently. Through the AusAID program, Aurora and other young people receive an education that will help them find employment outside Kiribati and support their large extended families after their family members have joined them.

But it is a tough transition. Another nursing student says he feels like he is losing his identity as his nation sinks into the sea. Some students’ parents refuse to leave Kiribati. They see the changes in sea level and rainfall, but as Christians they believe that “God is not so silly to allow people to perish just like that.”

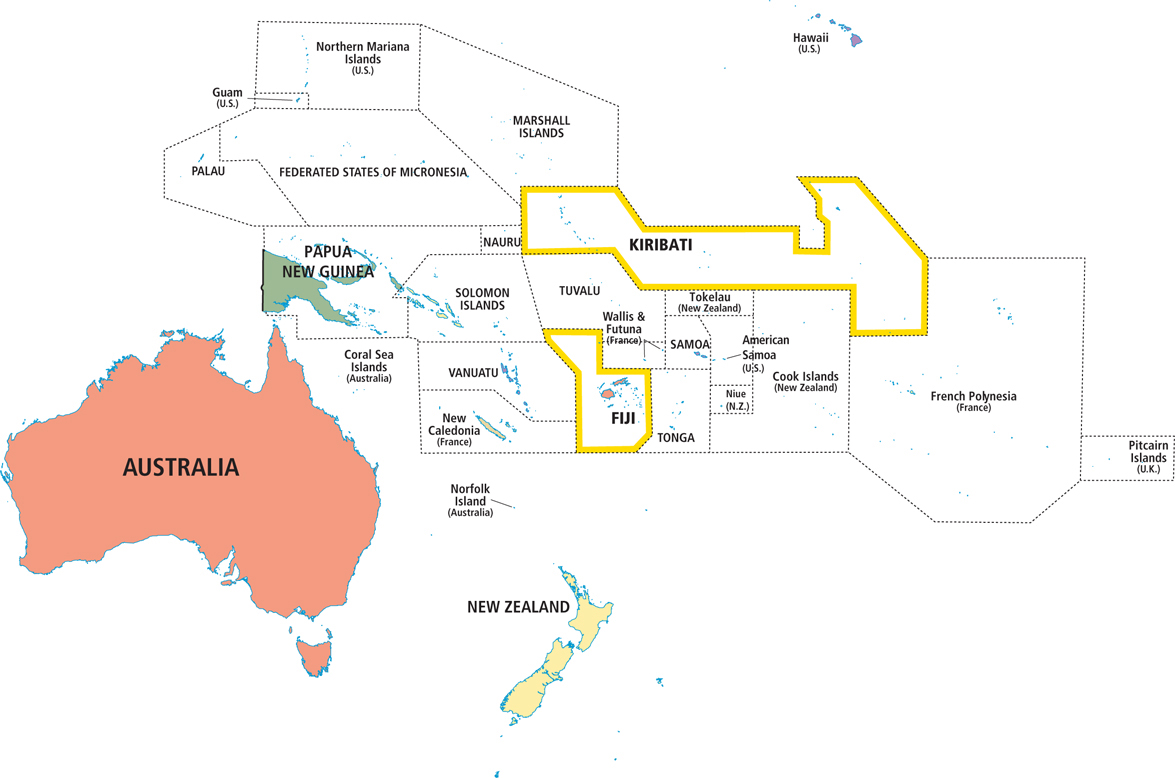

In March 2012, the BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation) reported that President Tong had approached landowners on the island nation of Fiji, 1300 miles to the south (Figure 11.3), hoping to buy Fijian land. His goals are twofold: to produce food to export to Kiribati and to import Fijian soil to replace the soil lost to sea level rise in Kiribati. This proposition will surely trigger controversy in Fiji, which already has its own social and political problems. [Sources: National Public Radio; BBC News Asia. For detailed source information, see Text Sources and Credits.]

Perhaps nowhere else on Earth are the effects of climate change as measurably real as they are in the low-