11.2 PHYSICAL GEOGRAPHY AND ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES

What Makes Oceania a Region?

Oceania is made up of Australia, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, and the many small islands scattered across the Pacific Ocean (see Figure 11.3). It is a unique world region in that it is composed primarily of ocean and covers the largest area of Earth’s surface of any region, yet it is home to only 38.7 million people, the vast majority of whom live in Australia (22.7 million), Papua New Guinea (6.9 million), and New Zealand (4.4 million). In this book, we also include the U.S. state of Hawaii (1.7 million) in Oceania. All together, the thousands of other Pacific islands are home to only 3 million people. The Pacific Ocean is the link that unites Oceania as a region, profoundly influencing life even on dry land, but across the region, the ocean also acts as a biological and cultural barrier.

Terms in This Chapter

Some maps in this chapter show different place-

11.2.1 PHYSICAL PATTERNS

The Pacific Ocean serves as both a link and a barrier in Oceania. Plants and animals have found their way from island to island by floating on the water, swimming, or flying, and humans have long used the ocean as a way to make contact with other peoples for visiting, trading, and raiding. Unfortunately, as we shall see, the ocean also serves as a conveyer of pollution, especially discarded plastics. But the wide expanses of water also profoundly limit the natural diffusion of plant and animal species and keep Pacific Islanders spatially isolated from one another. The vast ocean has imposed solitude and fostered self-

Continent Formation

The largest landmass in Oceania is the ancient continent of Australia at the southwestern edge of the region (see the Figure 11.1 map). The Australian continent is partially composed of some of the oldest rock on Earth and has been relatively stable for more than 200 million years, with very little volcanic activity and only an occasional mild earthquake. Australia was once a part of the great landmass called Gondwana that formed the southern part of the ancient supercontinent Pangaea (see Figure 1.8). What became present-

Gondwana the great landmass that formed the southern part of the ancient supercontinent Pangaea

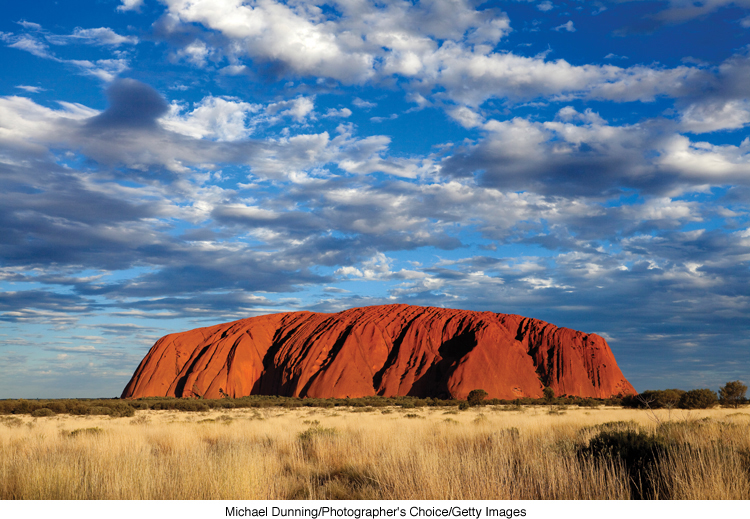

Australia is shaped roughly like a dinner plate with an irregularly broken rim with two bites taken out of it: one in the north (the Gulf of Carpentaria) and one in the south (the Great Australian Bight). The center of the plate is the great lowland Australian desert, with only two hilly zones and rocky outcroppings (see Figure 11.1B). The eastern rim of Australia is composed of uplands; the highest and most complex of these are the long, curving Eastern Highlands (labeled “Great Dividing Range” in the Figure 11.1 map; see also Figure 11.1A). Over millennia, the forces of erosion—

Off the northeastern coast of the continent lies the Great Barrier Reef, the largest coral reef in the world and a World Heritage Site since 1981 (see Figure 11.1E). It stretches along the coast of Queensland in an irregular arc for more than 1250 miles (2000 kilometers), covering 135,000 square miles (350,000 square kilometers). The Great Barrier Reef is so large that it influences Australia’s climate by interrupting the westward-

Great Barrier Reef the longest coral reef in the world, located off the northeastern coast of Australia

Island Formation

The islands of the Pacific were (and are still being) created by a variety of processes related to the movement of tectonic plates. The islands found in the western reaches of Oceania—

The Hawaiian Islands were produced through another form of volcanic activity associated with hot spots, places where particularly hot magma moving upward from Earth’s core breaches the crust in tall plumes. Over the past 80 million years, the Pacific Plate has moved across these hot spots, creating a string of volcanic formations 3600 miles (5800 kilometers) long. The youngest volcanoes, only a few of which are active, are on or near the islands known as Hawaii.

hot spots individual sites of upwelling material (magma) that originate deep in Earth’s mantle and surface in a tall plume; hot spots tend to remain fixed relative to migrating tectonic plates

Volcanic islands exist in three forms: volcanic high islands, low coral atolls, and makatea, which are coral platforms raised or uplifted by volcanism. High islands are usually volcanoes that rise above the sea into mountainous rocky formations which, because of their varying height and rugged landscapes, contain a rich variety of environments. New Zealand, the Hawaiian Islands, Mo’orea, and Easter Island are examples of high islands (see Figure 11.1D, F). An atoll is a low-

atoll a low-

Climate

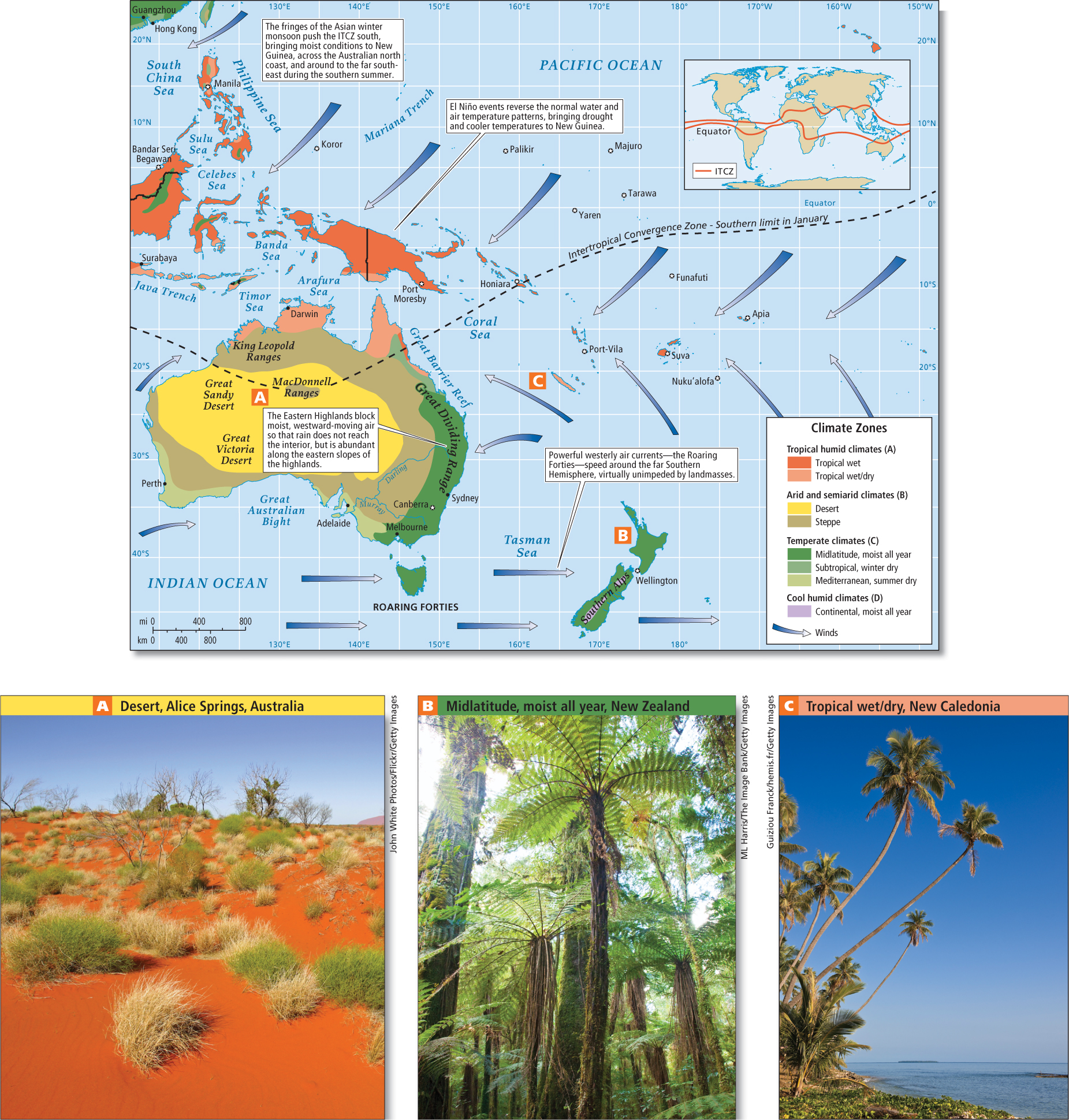

Although the Pacific Ocean stretches almost from pole to pole, most of the land of Oceania is situated within the Pacific’s tropical and subtropical latitudes. The tepid water temperatures of the central Pacific bring mild climates year-

Moisture and Rainfall With the exception of the vast arid interior of Australia, much of Oceania is warm and humid nearly all the time. New Zealand and the high islands of the Pacific receive copious rainfall; before human settlement, they supported dense forest vegetation. Now, after 1000 years of human impact, much of that forest is gone (see Figure 11.5B; see also Figure 11.9D).

Travelers approaching New Zealand, either by air or by sea, often notice a distinctive long white cloud that stretches above the north island. Seven hundred years ago, early Maori settlers (members of the Polynesian group) also noticed this phenomenon and they named that place Aotearoa, “land of the long white cloud,” a name that is now applied to all of New Zealand.

Maori Polynesian people indigenous to New Zealand

The legendary Roaring Forties (named for the 40th parallel south) are powerful air and ocean currents that speed around the far Southern Hemisphere virtually unimpeded by landmasses. These westerly winds (winds that blow west to east), which are responsible for Aotearoa’s distinctive bodies of moist air, deposit a drenching 130 inches (330 centimeters) of rain per year in the New Zealand highlands and more than 30 inches (76 centimeters) per year on the coastal lowlands (see Figure 11.5B). At the southern tip of New Zealand’s North Island, the wind averages more than 40 miles per hour (64 kilometers per hour) nearly 120 days per year. Farmers in the area stake their cabbages to the ground so the plants will not blow away.

Roaring Forties powerful air and ocean currents at about 40° S latitude that speed around the far Southern Hemisphere virtually unimpeded by landmasses

By contrast, two-

Overall, Australia is so arid that it has only one major river system, which is in the temperate southeast where most Australians live. There, the Darling and Murray rivers drain one-

In the island Pacific, mountainous high islands also exhibit orographic rainfall patterns, with a wet windward side and a dry leeward side (see Figure 11.5C). Rainfall amounts on the low-

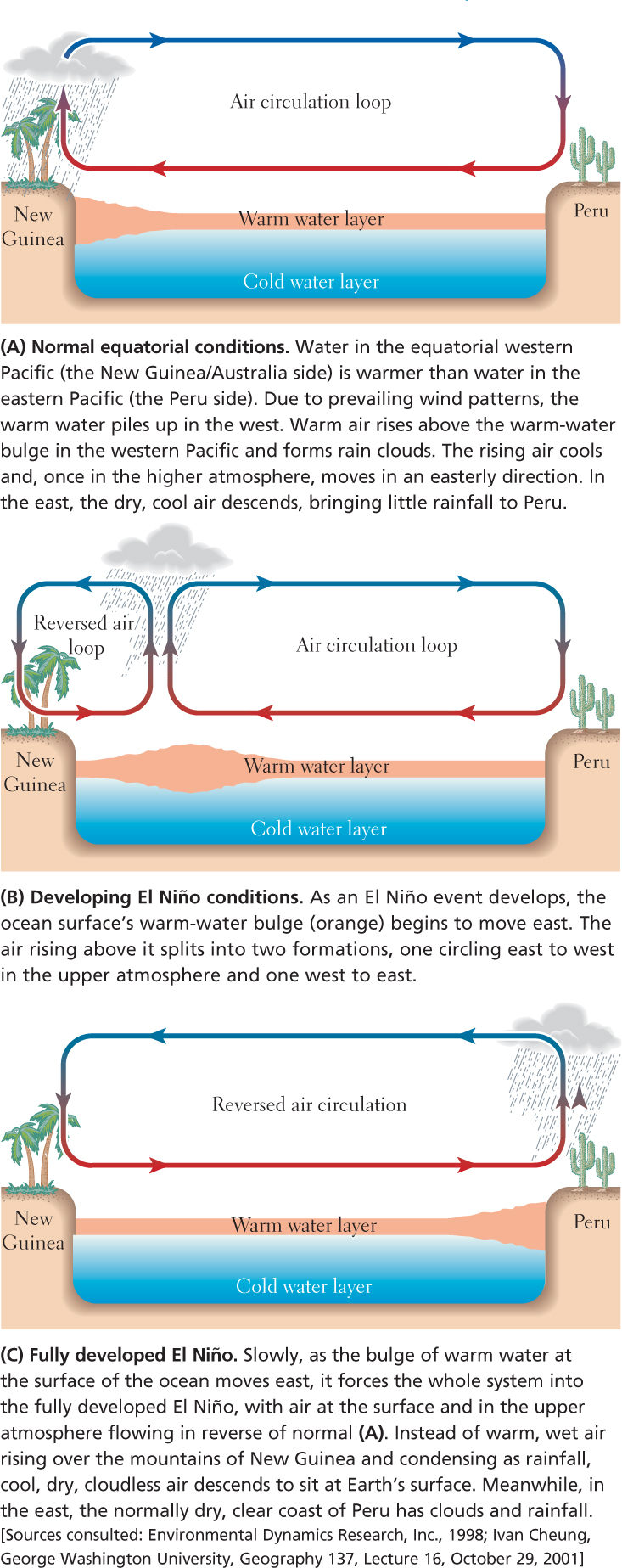

El Niño Recall from Chapter 3 the El Niño phenomenon, a pattern of shifts in the circulation of air and water in the Pacific that occurs irregularly every 2 to 7 years. Although these cyclical shifts, or oscillations, are not yet well understood, scientists have worked out a model of how the oscillations may occur (Figure 11.6).

The El Niño event of 1997–

In the 1980s, an opposite pattern in which normal weather conditions become intensified was identified and named La Niña. It is now understood that La Niña patterns can bring unusually severe precipitation events (including tornadoes and blizzards) to places from the Indian Ocean to North America. La Niña is thought to have played a role in the major floods of 2010–

Fauna and Flora

The fact that Oceania is comprised of an isolated continent and numerous islands has affected its animal life (fauna) and plant life (flora). Many of its species are endemic, meaning that they exist in a particular place and nowhere else on Earth. This is especially true in Australia (of the 750 species of birds known in Australia, more than 325 species are endemic), but many Pacific islands also have endemic species.

endemic belonging or restricted to a particular place

Animal and Plant Life in Australia The uniqueness of Australia’s animal and plant life is the result of the continent’s long physical isolation, large size, relatively homogeneous landforms, and arid climate. Since Australia broke away from Gondwana more than 65 million years ago, its animal and plant species have evolved in isolation. One spectacular result of this isolation is the presence of more than 144 living species of endemic marsupial animals. Marsupials are mammals whose babies at birth are still at a very immature stage; the marsupial then nurtures them in a pouch equipped with nipples. The best-

marsupials mammals whose babies at birth are still at a very immature stage; the marsupial then nurtures them in a pouch equipped with nipples

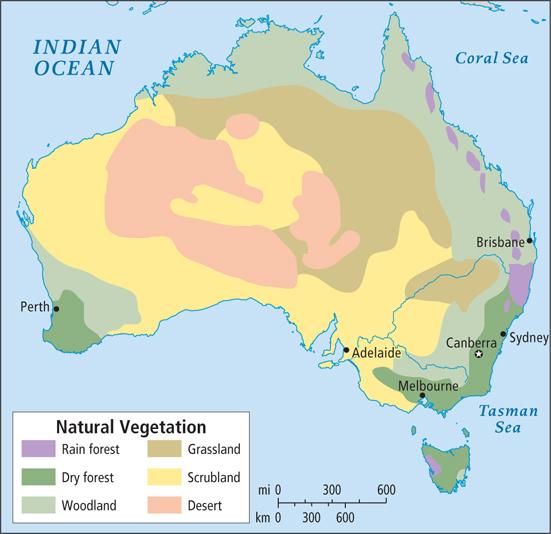

monotremes egg-

Most of Australia’s endemic plant species are adapted to dry conditions. Many of the plants have deep taproots to draw moisture from groundwater, and small, hard, pale green or shiny leaves to reflect heat and to hold moisture. Much of the continent is grassland and scrubland with bits of open woodland; there are only a few true forests, found in pockets along the Eastern Highlands and the southwestern tip and in Tasmania (Figure 11.7). Two plant genera account for nearly all the forest and woodland plants: Eucalyptus (450 species, often called gum trees) and Acacia (900 species, often called wattles).

Plant and Animal Life in New Zealand and the Pacific Islands Naturalists and evolutionary biologists have had a great interest in the species that inhabited the Pacific islands before humans arrived. Charles Darwin formulated many of his ideas about evolution after visiting the Galápagos Islands of the eastern Pacific (see the Figure 3.1 map) and the islands of Oceania.

Islands gain plant and animal populations from the sea and air around them as organisms are carried from larger islands and continents by birds, storms, or ocean currents. Once these organisms “colonize” their new home, they may evolve over time into new species that are unique to one island. High, wet islands generally contain more varied species because their more complex environments provide niches for a wider range of wayfarers and thus more opportunities for evolutionary change.

Once they arrive, human inhabitants modify the flora and fauna of islands. In prehistoric times, Asian explorers in oceangoing canoes brought plants such as bananas and breadfruit and animals such as pigs, chickens, and dogs to Oceania. European settlers later brought grains, vegetables, fruits, invasive grasses, cattle, sheep, goats, rabbits, housecats, and rats. Today, human activities from tourism to military exercises to urbanization continue to change the flora and fauna of Oceania.  240. BREADFRUIT ADVOCATES SAY IT COULD SOLVE HUNGER IN TROPICAL REGIONS

240. BREADFRUIT ADVOCATES SAY IT COULD SOLVE HUNGER IN TROPICAL REGIONS

Generally, the diversity of land animals and plants is richest in the western Pacific, near the larger landmasses. It thins out to the east, where the islands are smaller and farther apart. The natural rain forest flora is rich and abundant in New Zealand and New Guinea, and also on the high islands of the Pacific. However, the natural fauna is much more limited on these islands. While New Guinea has fauna comparable to Australia, to which it was once connected via Sundaland (see Figure 10.5), New Zealand and the Pacific islands have no indigenous land mammals, almost no indigenous reptiles, and only a few indigenous species of frogs, as they were never connected to Australia and New Guinea by a land bridge that land animals could cross. Two indigenous birds in New Zealand, the kiwi and the huge moa (a bird that grew up to 12 feet [3.7 meters] tall), were a major source of food for the Maori people. The moa was hunted to extinction before the Europeans arrived. Today, New Zealand may well be the country with the most nonnative species of mammals, fish, and fowl, nearly all brought in by European settlers.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

This largest region of the world is primarily water and has a very small population of just 38.7 million people.

The largest land area in Oceania is the continent of Australia.

The thousands of islands of the Pacific were created either as a result of plate tectonics or volcanic activity.

The climate of most of the region is warm and humid almost all the time.

Due to their isolation from the life forms found on other major land-

masses, the fauna and flora of the region are unique in many distinctive ways that have informed our knowledge about evolution. Many species, such as marsupials and monotremes, are endemic to the region.