11.5 GLOBALIZATION AND DEVELOPMENT

GEOGRAPHIC INSIGHT 2

Globalization and Development: Globalization, coupled with Oceania’s stronger focus on neighboring Asia (rather than on its long-

Globalization, Development, and Oceania’s New Asian Orientation

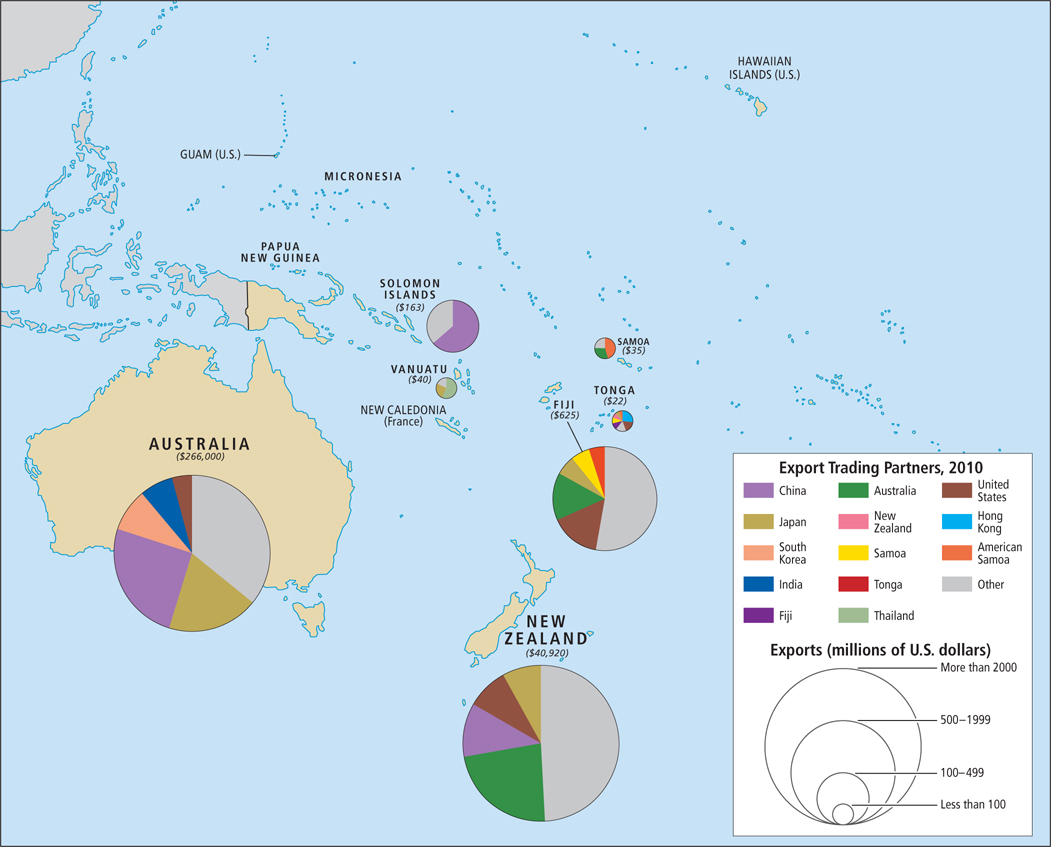

One could say that globalization in Oceania began when the first European explorers came into the region, beginning the trend of influence by outsiders (primarily Europeans) on settlement, culture, and economics. More recently, the United States has exerted a powerful influence on trade and politics in the region. For the past several decades, however, globalization has reoriented this region toward Asia, which buys more than 76 percent of Australia’s exports (mainly coal, iron ore, and other minerals). In 2011, China and India each purchased not only the output of mines, but also major shares of Australia’s coal deposits. Both countries use coal to generate energy and are trying to secure future access to more coal. Asia also buys nearly 35 percent of New Zealand’s exports (primarily meat, wool, and dairy products), as well as many other products and services from islands across Oceania (Figure 11.15).

Asia is also a major source of the region’s imports. Because there is little manufacturing in Oceania, most manufactured goods are imported from China, Japan, South Korea, Singapore, and Thailand—

The Pacific islands are further along in their reorientation toward Asia than are Australia and New Zealand. Not only are coconut, forest, and fish products from the Pacific islands sold to Asian markets, but Asian companies own more and more of these industries on the various islands. Fleets from Asia regularly fish the offshore waters of Pacific island nations. Asians also dominate the Pacific island tourist trade, both as tourists and as investors in tourism infrastructure. And growing numbers of Asians are taking up residence in the Pacific islands, exerting widespread economic and social influence.

The Stresses of Asia’s Economic Development “Miracle” on Australia and New Zealand

For Australia and New Zealand, Asia’s global economic rise has meant both more trade and more competition with Asian economies in foreign markets. Throughout Oceania, local industries used to enjoy protected or preferential trade with Europe. They have lost that advantage because EU regulations stemming from the EU’s membership in the World Trade Organization (WTO) prohibit such arrangements. No longer protected in their trade with Europe, local industries now face stiff competition from larger companies in Asia that benefit from much cheaper labor.

Australia and New Zealand are somewhat unusual in having achieved broad prosperity largely on the basis of exporting raw materials over a long period of time and to a wide range of customers (see Figures 11.14E and 11.15). Preferential trade with Europe allowed higher profits for many export industries. Strong labor movements in Australia and New Zealand meant that these industries’ profits were more equitably distributed throughout society than the profits in other raw materials–

Competition from Asian companies has also led to lower corporate profits in Oceania. As corporate profits have fallen, so have government tax revenues, which has resulted in cuts to previously high rates of social spending on welfare, health care, and education. The loss of social support, especially for those who have lost jobs, has contributed to rising poverty in recent years. Australia now has the second-

Maintaining Raw Materials Exports as Service Economies Develop Although their monetary contribution to national economies remains high, industries that export raw materials are of decreasing prominence in the economies of Australia and New Zealand in that they now employ fewer people because of mechanization. This shift to replacing human labor with machinery has been essential for these industries to stay globally competitive with other countries where living standards are lower and workers are paid much less.

Today, the economies of both Australia and New Zealand are dominated by diverse and growing service sectors, which have links to the region’s export sectors. Extracting minerals and managing herds and cropland have become technologically sophisticated enterprises that depend on many supporting services and an educated workforce. Australia is now a world leader in providing technical and other services to mining companies, sheep farmers, and winemakers, and New Zealand’s well-

Economic Change in the Pacific Islands In general, the Pacific islands are also shifting away from extractive industries, such as mining and fishing, and toward service industries, such as tourism and government. On many islands, self-

In the relatively poor and undereducated nations (the Solomon Islands, Tuvalu, and parts of Papua New Guinea, for example), conditions typify what has been termed a MIRAB economy—one based on migration, remittances, aid, and bureaucracy. Foreign aid from former or present colonial powers supports government bureaucracies that supply employment for the educated and semiskilled. A MIRAB economy has little potential for growth. Nevertheless, Islanders who can be self-

MIRAB economy an economy based on migration, remittances, aid, and bureaucracy

Where there is poverty, it is often related to geographic isolation, which means a lack of access to information and economic opportunity. Although computers and the new global communication networks are not yet widely available in the Pacific islands, they have the potential to significantly alleviate this isolation.

subsistence affluence a lifestyle whereby people are self-

The Advantages and Stresses of Tourism

Tourism is a growing part of the economy throughout Oceania. Tourists come largely from Japan, Korea, Taiwan, Southeast Asia, the Americas, and Europe (Figure 11.16). In 2008 (the latest year for which complete figures are available), 17.7 million tourists arrived in Oceania. Of the tourists visiting Oceania, 23 percent came from Asia—

In some Pacific island groups, the number of tourists far exceeds the island population. Guam, for example, receives tourists annually in numbers equivalent to five times its population. Palau and the Northern Mariana Islands annually receive more than four times their populations. Such large numbers of visitors expecting to be entertained and graciously accommodated can place a special stress on local inhabitants. And although they bring money to the islands’ economies, these visitors create problems for island ecologies, place extra burdens on water and sewer systems, and require a standard of living that may be far out of reach for local people. Perhaps nowhere else in the region are the issues raised by tourism as clear as they are in Hawaii.

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

Subsistence Affluence Practices Could Go Global

Many of the qualities of subsistence affluence practiced by Pacific Islanders, including local self-

CASE STUDY

Conflict over Tourism in Hawaii

Since the 1950s, travel and tourism have been the largest industries in Hawaii, producing nearly 18 percent of the gross state product in 2008. Tourism is related in one way or another to nearly 75 percent of all jobs in the state. (By comparison, travel and tourism account for 9 percent of GDP worldwide.) In 2008, tourism employed one out of every six Hawaiians and accounted for 25 percent of state tax revenues.

Dramatic fluctuations in tourist visits, often driven by forces far removed from Oceania, can wreak havoc on local economies. Decreases in tourism affect not just tourist facilities but supporting industries as well. For example, the construction industry thrives by building condominiums, hotels, resorts, and retirement facilities. The Asian recession of the late 1990s, the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, and the global recession of 2008–

Sometimes mass tourism can seem like an invading force to ordinary citizens. For example, an important segment of the Honolulu tourist infrastructure—

Another example of the impositions of mass tourism is the demand by tourists for golf courses on many of the Hawaiian Islands, which has resulted in what Native (indigenous) Hawaiians view as desecration of sacred sites. Land that in precolonial times was communally owned, cultivated, and used for sacred rituals was confiscated by the colonial government and more recently sold to Asian golf course developers. Now the only people with access to the sacred sites are fee-

As of 2012, there were more than 90 golf courses in Hawaii, and the golf industry alone contributed $1.6 billion to the state’s economy—

The Future: Diverse Global Orientations?

Despite the powerful forces pushing Oceania toward Asia, important factors still favor strong ties with Europe and North America. In spite of the trade links and China’s recent efforts to expand diplomatic and cultural relations with Australia, both Australia and New Zealand remain staunch military allies of the United States. Over the years, both have participated in U.S.-led wars in Korea, Vietnam, Afghanistan, and Iraq. In 2012, in an apparent effort to check the growing influence of the Chinese military in the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean, the Australian government gave the U.S. Marine Corps access to a large tract of land near Darwin (located in Australia’s Northern Territory). The United States and Australia also opened discussions regarding the use of the Cocos Islands (Australian possessions in the Indian Ocean) for reconnaissance purposes.

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

Sustainable Tourism

Some Pacific islands have attempted to deal with the pressures of tourism by adopting the principle of sustainable tourism, which is aimed at decreasing tourism’s imprint and minimizing disparities between hosts and visitors. For example Samoa, with financial aid from New Zealand, now develops and monitors sustainable tourism components (beaches, wetlands, and forested island environments) and provides knowledge-

In some of the Pacific islands, strong links to Europe and North America are also upheld by Europe and the U.S.’s continuing administrative control. In Micronesia, the United States governs Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands; in Polynesia, American Samoa is a U.S. territory. Just as the Hawaiian Islands are a U.S. state, the 120 islands of French Polynesia—

In 1989, Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) formed as a group of 21 Pacific countries. Today, these states account for approximately 40 percent of the world’s population, just over 50 percent of global production, and more than 40 percent of global trade. Its members include Oceania’s most populous countries (Australia, Papua New Guinea, and New Zealand), as well as Brunei, Canada, Chile, China, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, Mexico, Peru, the Philippines, Russia, Singapore, Taipei, Thailand, the United States, and Vietnam. APEC was organized to enhance economic prosperity and strengthen the Asia–

THINGS TO REMEMBER

GEOGRAPHIC INSIGHT 2

Globalization and Development Globalization, coupled with Oceania’s stronger focus on neighboring Asia (rather than on its long-

time connections with Europe), has transformed patterns of trade and economic development across Oceania. The transformation is being driven largely by Asia’s growing affluence, its enormous demand for resources, and its similarly massive production of manufactured goods. Service industries are becoming the dominant income source for most of Oceania’s economies, although extractive industries remain important.

Tourism is a significant and growing part of the economies in Oceania, but it can produce stresses for the host countries.

Oceania is at the center of a unique attempt (APEC) to forge international cooperation on food security, climate change, and energy-

efficient transportation.