11.9 SOCIOCULTURAL ISSUES

The cultural sea change in Oceania, away from Europe and toward Asia and the Pacific, has been accompanied by new respect for indigenous peoples. Increasing economic interdependence with Asia has diminished historic discrimination against Asians in this region.

Ethnic Roots Reexamined

Until very recently, most people of European descent in Australia and New Zealand thought of themselves as Europeans in exile. Many considered their lives incomplete until they had made a pilgrimage to the British Isles or the European continent. In her book An Australian Girl in London (1902), Louise Mack wrote: “[We] Australians [are] packed away there at the other end of the world, shut off from all that is great in art and music, but born with a passionate craving to see, and hear and come close to these [European] great things and their home[land]s.”

These longings for Europe were accompanied by racist attitudes toward both indigenous peoples and Asians. Most histories of Australia written in the early twentieth century failed to even mention the Aborigines, and later writings described them as amoral. At midcentury there were numerous projects to take Aboriginal children from their parents and acculturate them to European ways in boarding schools known for abuse and brutality. From the 1920s to the 1960s, whites-

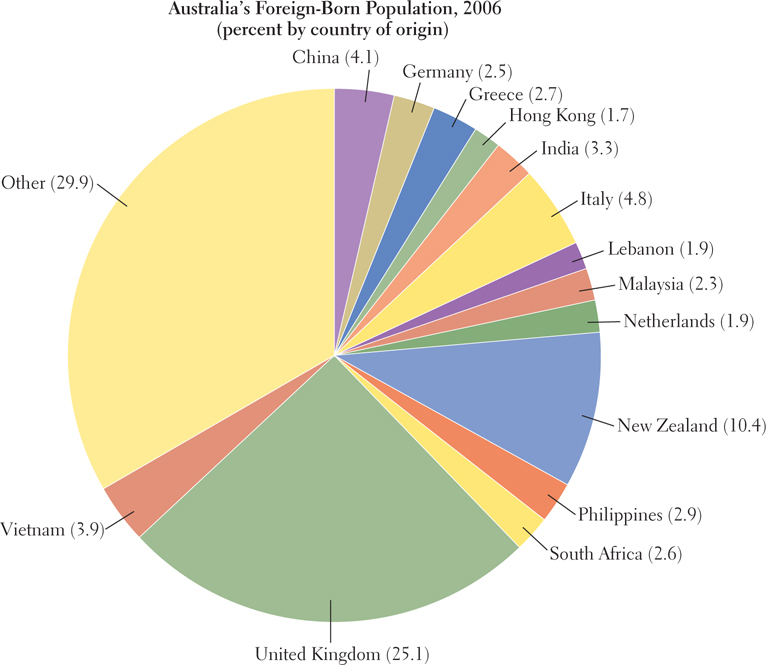

Weakening of the European Connection When migration from the British Isles slowed after World War II, both Australia and New Zealand began to lure immigrants from southern and eastern Europe, many of whom had been displaced by the war. Hundreds of thousands came from Greece, Italy, and what was then Yugoslavia. The arrival of these non-

As of 2010, more than one-

The Social Repositioning of Indigenous Peoples in Australia and New Zealand Perhaps the most interesting population change in Australia and New Zealand is one of identity. For the first time in 200 years, the number of people in both countries who claim indigenous origins is increasing. Between 1991 and 1996, the number of Australians claiming Aboriginal origins rose by 33 percent. By 2009, the Aboriginal population was estimated at 528,600. In New Zealand, the number claiming Maori background rose by 20 percent to 652,900 between 1991 and 2009.

These increases are due to changing identities, not to a population boom. More positive attitudes toward indigenous peoples have encouraged the open acknowledgment of Aborigine or Maori ancestry. Also, marriages between European and indigenous peoples are now more common. As a result, the number of people with a recognized mixed heritage is increasing.

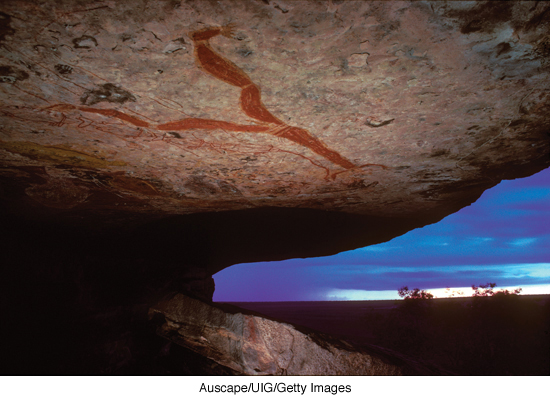

As society has acknowledged that discrimination has been the main reason for the low social standing and impoverished state of indigenous peoples, respect for Aboriginal and Maori culture has also increased. The Australian Aborigines base their way of life on the idea that the spiritual and physical worlds are intricately related (Figure 11.22). The dead are present everywhere in spirit, and they guide the living in how to relate to the physical environment. Much Aboriginal spirituality refers to the Dreamtime, the time of creation when the human spiritual connections to rocks, rivers, deserts, plants, and animals were made clear. However, very few Aboriginal people continue to practice their own cultural traditions or live close to ancient homelands. Instead, many live in impoverished urban conditions. In New Zealand, where the Maori constitute about 15 percent of the country’s population and Auckland has the largest Polynesian population (including Native Maori) of any city in the world, there are now many efforts to bring Maori culture more into the mainstream of national life.

Aboriginal Land Claims In 1988, during a bicentennial celebration of the founding of white Australia, a contingent of some 15,000 Aborigines protested that they had little reason to celebrate. During the same 200 years, they were assumed to have no prior claim to any land in Australia, they had lost basic civil rights, and they had effectively been erased from the Australian national consciousness. Into the 1960s, it was even illegal for Aborigines to drink alcohol.

British documents indicate that during colonial settlement, all Australian lands were deemed to be available for British use. The Aborigines were thought to be too primitive to have concepts of land ownership because their nomadic cultures had “no fixed abodes, fields or flocks, nor any internal hierarchical differentiation.” The Australian High Court declared this position void in 1993. After that, Aboriginal groups began to win some land claims, mostly for land in the arid interior previously controlled by the Australian government. Figure 11.23 shows the Aboriginal Tent Embassy in 2012, versions of which have stood on the grounds of Parliament in Canberra for more than 40 years. The Aboriginal Tent Embassy was instrumental in raising public awareness of injustices and remains a national symbol of Aboriginal civil rights. Court cases and other efforts to restore Aboriginal rights and lands continue (see Figure 11.17D).

Maori Land Claims In New Zealand, relations between the majority European-

By 1950, the Maori had lost all but 6.6 percent of their former lands to European settlers and the government. Maori numbers had shrunk from a probable 120,000 in the early 1800s to 42,000 in 1900, and the Maori came to occupy the lowest and most impoverished rung of New Zealand society. In the 1990s, however, the Maori began to reclaim their culture, and they established a tribunal that forcefully advances Maori interests and land claims through the courts. Since then, nearly half a million acres of land and several major fisheries have been transferred back to Maori control. Nonetheless, the Maori still have notably higher unemployment, lower education levels, and poorer health than the New Zealand population as a whole.

Forging Unity in Oceania

Although wide ocean spaces and the great diversity of languages in the region sometimes make communication difficult, travel, sports, and festivals (Figure 11.24) are three forces that help bring the people of Oceania closer together.

Languages in Oceania The Pacific islands—

Languages are both an important part of a community’s cultural identity and a hindrance to cross-

pidgin a language used for trading; made up of words borrowed from the several languages of people involved in trading relationships

Interisland Travel One way in which unity is manifested in Oceania is interisland travel. Today, people travel in small planes from the outlying islands to hubs such as Fiji, where jumbo jets can be boarded for Auckland, Melbourne, and Honolulu. Cook Islanders call these little planes “the canoes of the modern age,” and people travel for many reasons. Dancers from across the region attend the annual folk festival in Brisbane; businesspeople from Kiribati, Micronesia, can fly to Fiji to take a short course at the University of the South Pacific; a Cook Islands teacher can take graduate training in Hawaii; and sports fans can visit multiple locations over time.

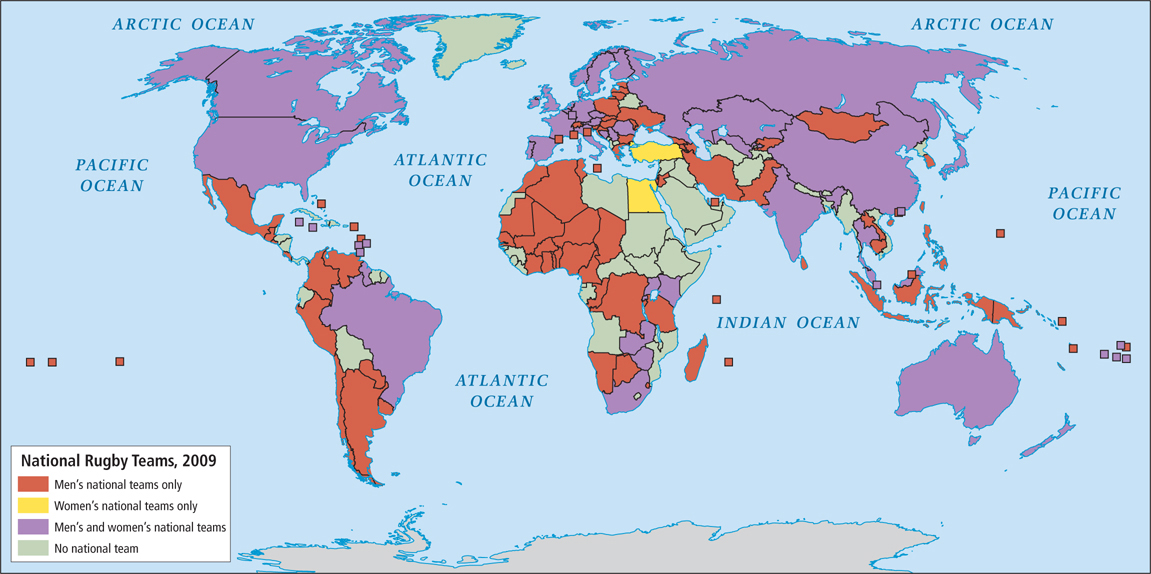

Sports as a Unifying Force Sports and games are a major feature of daily life throughout Oceania. The region has shared sports traditions with and borrowed them from cultures around the world. Surfing evolved in Hawaii and, like outrigger sailing and canoeing, derives from ancient navigational customs that matched human wits against the power of the ocean. On hundreds of Pacific islands and in Australia and New Zealand, rugby, volleyball, soccer, and cricket are important community-

Pan-

The haka (Figure 11.25) is an example of how, in the post-

Outside Oceania, those who perform the haka include the rugby teams at Jefferson High in Portland, Oregon, and Middlebury College in Vermont, and the football teams at Brigham Young University and the University of Hawaii. All these teams have players who are of Polynesian heritage. Most practitioners speak of the haka as filling them with the necessary exuberance, aggression, and spirituality to play a vigorous and successful game. To see videos of a haka, go to http:/

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Oceania’s long-

standing cultural and economic links to Europe are being challenged by reinvigorated native traditions and identities and by economic globalization, which is strengthening the region’s links to Asia. The number of Asian immigrants into Australia and New Zealand has been increasing over the past two decades, while the number of Europeans has been declining. Asians, however, still make up only a small minority of the populations of both Australia and New Zealand.

Sports and festivals are unifying forces for the region, inspiring fund-

raisers that allow ordinary citizens to travel to games, thus reinforcing regional and ethnic identity.