Lessons from KIPP Delta

Lessons from KIPP Delta

ROBERT MARANTO AND JAMES V. SHULS

Lessons from KIPP Delta

A KIPP school in an Arkansas backwater succeeds by tightly focusing on its mission of getting kids into and through college, then organizing tactics and strategies around that goal.

Consider these grim statistics: Helena–West Helena is the seat of Phillips County, the second poorest county in Arkansas. The town was home to more than 40,000 people in the 1960s; now, it has fewer than 13,000 residents, and they have a median household income of $24,427 (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2011a). Federal data show that only 62.2% of adults have high school diplomas; only 12.4% have completed college (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2011b). In 2010, just 36% of Helena–West Helena 10th graders scored proficient or advanced on the Arkansas literacy exam.

In spite of these numbers, in the second poorest county in the second poorest state, one school—nine-year-old KIPP Delta—has done remarkably well. There is no secret to its success. Most of KIPP Delta’s playbook might work at other high-poverty public schools. We conducted 12 days of fieldwork at KIPP Delta over the last two years and interviewed most of the teachers and administrators. To cut to the chase, we think KIPP’s culture explains the school’s academic success, and we believe that aspects of its culture are broadly replicable.

KIPP Delta Results

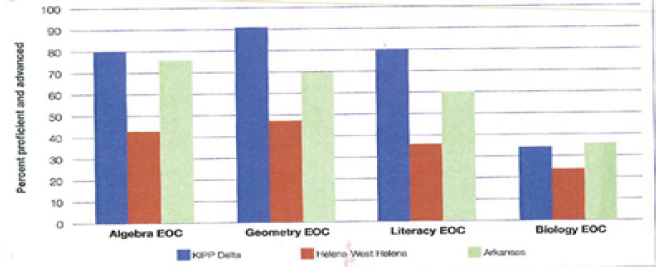

In spring 2011, KIPP Delta had just over 700 students in elementary school, middle school, and high school at its Helena–West Helena site, along with 55 students in its new middle school two hours north in Blytheville. The “KIPPsters” are 97% black and 86% eligible for free or reduced-price lunch, with slightly more minority students but poverty levels comparable to nearby public schools. Both KIPP Delta and nearby school districts struggle to find qualified teachers, and are listed as geographic shortage areas by the Arkansas Department of Education. Both rely heavily on Teach For America (TFA) because few traditionally certified teachers want to live in the area. Though the schools hire teachers from the same pool and the students are similar demographically, students at KIPP Delta perform significantly better on state exams, as Figure 1 shows. Further, our value-added data show KIPP Delta to be the best public school in the region, and among the best in the state.

KIPP Delta focuses on getting KIPPsters to and through college. All 23 members of the class of 2010, the first graduating class, earned admission at four-year colleges, a feat repeated by the 27 2011 graduates. The mean ACT score for the class of 2010 was 22.7, above the Arkansas (20.3) and national (21.0) means. How does KIPP Delta prepare disadvantaged students to climb the mountain to college?

Criticisms of KIPP

5

KIPP Delta is part of the national chain of KIPP (Knowledge is Power Program) charter schools, founded in 1994 in Houston. The 99 KIPP campuses in 20 states have won praise from education reformers including Bill Gates and U.S. Education Secretary Arne Duncan, as well as criticism from some who believe that KIPP schools cut corners to achieve high test scores. Chiefly, critics argue that KIPP must be creaming or cropping.

Creaming

Some school superintendents we know, as well as academic critics like Horn (2011), charge that KIPP “creams” by selectively admitting higher-performing students. Yet, student-level quantitative analyses at 22 KIPP middle schools by Tuttle et al. (2010) find no such differences between new KIPPsters and peers at nearby traditional public schools. KIPP Delta admits all students who apply, holding a lottery when a grade is oversubscribed. KIPP Delta’s new campus in Blytheville intentionally located at a site that as one KIPP parent complained, “seems like a downgrade” in comparison to district schools in better neighborhoods. The principal explained that KIPP needed to be where parents most need alternatives.

Cropping-Selective Attrition

Miron et al. (2011) claim that KIPP encourages selective attrition of low-performing students, finding that KIPP campuses have significantly higher transfer rates than school districts. But that analysis compares turnover at KIPP campuses with that of the entire school district they are located in, and does not count intradistrict transfers. That way a traditional public school student who transfers (or is assigned) to a different school in the same district, or even an alternative school, is not counted as turnover. Given that all high-poverty schools have considerable student churn, using the whole district as a unit of analysis assures that KIPP schools, most of which are single sites, won’t compare favorably.

Single-school comparisons find different results. Using student-level data, Nichols-Barrer et al. (2011) compare attrition levels at 22 KIPP middle schools and neighboring traditional public schools and find that over the entire course of middle school, “cumulative attrition rates at KIPP schools in our sample are similar to those of schools in their surrounding district.” Using the same student-level data, the same research team (Tuttle et al., 2010) found KIPP’s performance is not explained by student attrition, which again, resembles that for nearby traditional public schools. Of course, even KIPP backers like Mathews (2009) admit that individual campuses have had high attrition, particularly in their first year. Further, KIPP is rapidly expanding and evolving, so more research is needed. At this point, we can only say that student-level comparisons indicate that claims of creaming and cropping are vastly overstated.

Paternalism

In addition to statistical criticisms, there are ideological ones. Social justice intellectuals reject KIPP’s no-excuses philosophy, which they contend exploits disadvantaged students by brainwashing them to seek individual success through hard work and education credentials rather than community success through collective political action. These critics don’t believe that any school, whether in disadvantaged or privileged areas, should emphasize procedures and discipline, a point we will return to below (Grey, 2011; Horn, 2011). As Horn (2011, p. 83) laments, “KIPP does not depart too far from the conventional structures that our parents and our parents’ parents would recognize as school.” Such views are strongly held. For example, at the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the Future of U.S. “Public” Schools panel we attended at the 2011 AERA annual meeting, one presenter who denounced KIPP was asked if he’d ever visited a KIPP campus. He said no, retorting that while he’d never been in a concentration camp, he understood how they operate. To such critics, we make two suggestions. First, those without experience inside KIPP schools should show some modesty about judging them. Second, it seems both unscientific and authoritarian to declare that only progressive teaching techniques are permissible. To us, it seems paternalistic in the extreme for professors to declare that parents who choose KIPP schools for their children don’t know what they’re doing.

Lessons of KIPP Delta

10

At KIPP Delta, like most KIPP schools, KIPPsters take a three-week summer school, primarily to “KIPPnotize” them into school culture. We observed this process at both KIPP Delta sites, finding the following lessons that other schools might implement.

1. Define the mission; hire for it.

KIPP Delta students, parents, and staff understand the school’s mission: getting students to and through college. College pennants adorn the walls. KIPPsters are often referred to as “scholars.” Staffers seek opportunities to emphasize that the ultimate goal is climbing the mountain to college. On the first day of summer school, kindergarten students were greeted with signs reading “Good Morning Class of 2023.” At one point, a crying student could not be consoled by her teacher, an event not uncommon at the start of kindergarten. The principal comforted the girl in the hallway, saying softly “honey, I want you to go back in there so you can learn so much so you can go to college when you get bigger. Do you want to be a doctor or a teacher like your teacher?” While waiting with students for the bus, teachers reminisced about college, and spoke with 5th graders about where they might want to attend. The college focus was omnipresent.

Not every school needs this mission, but all schools should have some mission to guide important decisions, especially staffing. During teacher recruitment, KIPP Delta looks not just for teachers with the right academic credentials, but for teachers who embrace the mission. In job interviews, prospective teachers are given scenarios in which they must choose between following superiors, or doing whatever it takes to prepare students for college. In such conflicts, the mission determines the decision: KIPP Delta seeks teachers who would disobey authority to help students. In a national study, we examined the personnel recruitment web sites of 33 KIPP schools and 34 nearby traditional public schools, finding that KIPP makes comparatively less use of materialistic (salary, benefits) appeals and more use of public service (mission) appeals in teacher recruitment.

2. Sweat the small stuff.

In The First Days of School: How to Be an Effective Teacher, Wong and Wong (1997, p. 141) write that effective teachers “introduce rules, procedures, and routines on the very first day of school and continue to teach them the first week of school. During the first week of school, rules, procedures, and routines take precedence over lessons.” KIPP offers Wong on steroids, not just for the first week, but for the entire three-week summer school, developing a culture where learning can proceed free of disciplinary distractions.

We observed this at the start of summer school. On reaching school, KIPPsters were greeted with a smile and a handshake and taught how to walk in straight lines. They were then instructed in breakfast, told in considerable specificity how to pass the food and dispose of trash. After breakfast, students were taken to the lavatory, again in neat lines, and urged to clean up after themselves to “leave it better than you found it.” In the elementary school, the teachers even demonstrated how to use the bathrooms appropriately to avoid congestion and infection. Teachers and the principals constantly praised students for exhibiting the desired behavior, as in:

“I like how you waited until being called on.”

“That’s a very good way to say that.”

“I really like the way you asked that question.”

“I like how you saw that paper on the floor and threw it away.”

“I like the way you are sitting up straight and paying attention without being told.”

15

In one case, teachers praised a student the next day for having taken a neighbor’s garbage can out of the street after he was dropped off. While teachers constantly evaluated students, they exhibited praise and encouragement more than criticism, and constantly connected behavior to larger goals like success in college, and caring for others, modeling the KIPP motto of “work hard; be nice.”

After lunch, students learned how to organize their agenda (“your life”) and homework folders. They were also instructed in their first homework assignment, calling their teacher’s cell phone that evening to make sure they knew how to reach the teacher after hours. By day two, teachers were checking homework and making phone calls to parents, as needed.

The first days were also about respect, with teachers immediately punishing the one minor act of pushing by sending both students to the office and calling both mothers. A teacher also created a “teachable moment” when students tittered at a peer’s wrong answer. Going from a very light, energetic lesson on multiplication into a very serious, angry tone, the teacher said:

I will say this once and not again. In this class, laughter will never be used to make fun of another student. Laughter will be for joy, or occasionally it may be directed at me, but laughter will NEVER be used to make fun of another student or to divide this class, or you will have a problem with ME. Do I make myself clear?

The class responded “YES, SIR!” While some may see this as paternalistic, to us the exchange promoted a culture in which KIPPsters can make mistakes without fearing ridicule.

3. Develop schoolwide consistency.

A strong culture is a common culture. In each class we observed, teachers used the same terms and held students to the same expectations; thus, students knew what’s expected of them from every adult in the school. This makes classroom management easier, removing the “I didn’t know” excuse. Students knew the expectations, and teachers knew their peers had their backs. At the new Blytheville campus, we saw this consistency developing in frequent staff meetings and informal interactions in the weeks before summer school opened.

20

Again, not all schools have KIPP’s mission, but all can have a common culture dictated by mission. A fundamental principle of classroom management is consistency, but in-class consistency only goes so far. For schools to run smoothly, behavior must be consistent throughout the building, or disruptive classes may affect all classes. Consistency limits the tensions caused by varying expectations of student behavior. This level of consistency requires leadership and teacher buy-in.

4. Build relationships.

Successful schools often attempt what political scientists refer to as “co-production” of public service. At KIPP Delta, this translates to empowering parents to work with the school. KIPP principals call, and indeed often badger, newly admitted KIPP parents to attend the “commitment meeting.” At that meeting, the parent, the KIPPster, and a KIPP staffer read their respective KIPP Commitments to Excellence, promising to do whatever is necessary to assure academic success. All three sign, and then another staffer photos all three displaying the signed commitment. Further, teachers and administrators typically do home visits, often visiting the same family more than once. As one KIPPster bragged, “these teachers are crazy . . . my teacher actually called me up and asked me and my family out to dinner—I mean who does that?” KIPP principals and teachers typically know all their students—something made easier since most campuses are small. Such relationship building is particularly important in low-income communities (Chenoweth, 2009).

5. Give principals the power to lead.

KIPP principals control staff, budgets, and calendars. As Ouchi (2009) writes, the most effective traditional public school systems also invest considerable authority in principals. Compared to central office staff, principals know more about their schools, can better build relationships, and can move more quickly to meet student and staff needs. Empowering principals is easier for a charter than a traditional school district. Still, Ouchi’s work in effective urban districts, and our own fieldwork in successful high-poverty schools like Grace Hill Elementary in Rogers, Ark., suggests that traditional public schools can empower principals.

6. Measure success frequently.

KIPP leaders and teachers told us that they constantly track student academic performance, and that they and KIPPsters are motivated by steady progress toward the ultimate goal, entering and succeeding in college. Constant feedback is key. As one leader put it, students would not enjoy video games if they had to wait three months to get their scores. Where possible, KIPPsters get immediate feedback from formative assessments. Further, since success is measured by standardized tests, academic achievement is not seen as a zero-sum game. Teachers expect KIPPsters to help peers. For staff and students, the desired outcome is for all KIPPsters to do well.

Conclusions

KIPP Delta succeeds at its stated mission, probably because of its careful attention to culture building. Some say there is no secret to building school culture. A KIPP Delta principal claims:

You build culture through establishing really clear expectations, and then you have to constantly reinforce those expectations. You tell students exactly what you want. Then, you rehearse and rehearse with feedback until it becomes habit. There is no magic to building culture; it’s just hard work.

25

We think this is not quite right. Most educators work hard. What distinguishes KIPP is not just hard work, but thoughtful work linking the daily processes of schooling to the goals of schooling, in this case success in college. Day-to-day tactics reflect broader themes: having a clear mission and hiring staff who support the mission, building student culture to support the mission, ensuring consistency, building relationships, empowering principals to lead, and using frequent measurement of success to motivate teachers and students. These, we believe, are lessons for all schools.

References

Chenoweth, K. (2009). How it’s being done: Urgent lessons from unexpected schools. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Grey, L. (2011). Governing identity through neoliberal education initiatives. In P. E. Kovacs (Ed.), The Gates Foundation and the future of U.S. “public schools” (pp. 126–144). New York, NY: Routledge.

Horn, J. (2011). Corporatism, KIPP, and cultural eugenics. In P.E. Kovacs (Ed.). The Gates Foundation and the future of U.S. “public schools” (pp. 80–103). New York, NY: Routledge.

Mathews, J. (2009). Work hard. Be nice. Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin Books.

Miron, G., Urschel, J., & Saxton, N. (2011). What makes KIPP work? A study of student characteristics, attrition, and school finance. New York, NY: National Center for the Study of Privatization in Education.

Nichols-Barrer, I., Tuttle, C. C., Gill, B., & Gleason, P. (2011). Student selection, attrition, and replacement in KIPP middle schools. Washington, DC: Mathematica Policy Research.

Ouchi, W. G. (2009). The secret of TSL. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Tuttle, C. C., Teh, B., Nichols-Barrer, I., & Gleason, P. (2010). Student characteristics and achievement in 22 KIPP middle schools. Washington, DC: Mathematica Policy Research.

U.S. Department of Agriculture. (2011a). County-level unemployment and median household income for Arkansas. Washington, DC: Author.

U.S. Department of Agriculture. (2011b). State fact sheets. Washington, DC: Author.

Wong, H. K. & Wong, R. T. (1997). The first days of school: How to be an effective teacher. San Francisco, CA: Harry K. Wong Publications.

Post-Reading

Compare and contrast the perspective of this article with the perspective of one other article in this chapter. How are the perspectives similar? How do they differ? What might account for their differences? Go back to the article you’re comparing this with and make additional notes about how the article relates to this one. For more on comparison and contrast as a strategy, see Chapter 7, Rhetorical Patterns in Reading and Writing, page 000 in your book.

COMPREHENSION QUESTIONS

Question

1. According to the article, what are two criticisms of the KIPP schools? How does the article address these criticisms?

Question

2. What conclusions do the authors come to about what distinguishes a KIPP school from a traditional school?

Question

3. What is “creaming” in education (para. 6)?

Question

4. What is “cropping” in education (para. 7)?

Question

5. According to the authors, why is a “common culture” in a school so helpful in educating students?

VOCABULARY ACTIVITIES

Question

1. Add any words from this article to your ongoing education glossary. Remember to write definitions in your own words.

Question

2. Maranto and Shuls use some education jargon in this article. Make a list of all the terms that you would identify as “jargon” or technical language, and then use your understanding of roots, prefixes, and suffixes to help figure out the meaning. How does the use of education jargon help you to identify the audience for this article? For more on roots, prefixes, and suffixes, see Chapter 8, Vocabulary Building, page 000 in your book.

SUMMARY ACTIVITY

Using the headings in the reading as a guide, write a nutshell summary for each section of the text. How well does this help you summarize the main points of the article? Based on this activity, write a one-paragraph summary of the reading. For information on summary writing, see Chapter 1, Reading and Responding to College Texts, p. 000 in your book.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

Question

1. Why does KIPP put so much emphasis on college even as early as kindergarten?

Question

2. How does the KIPP school experience as described in the article compare to your grade school or middle school experience?

Question

3. Where do Maranto and Shuls address counterarguments against charter schools? Reread that section and analyze how fairly they present the views of those who oppose charter schools and how well they address these views.

Question

4. What makes this profile of a KIPP school persuasive or not persuasive? What choices do the authors make that encourage you to agree with them?

Question

5. Why are experts so passionately divided over the question of charter schools? What is at stake in this debate?