Peer Relationships

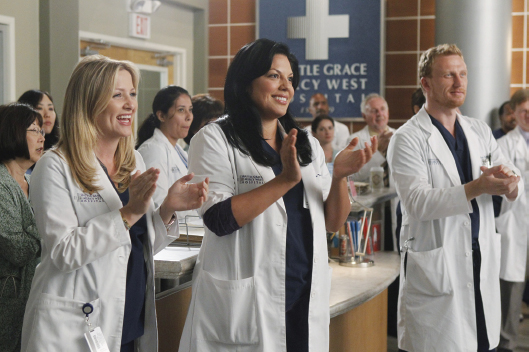

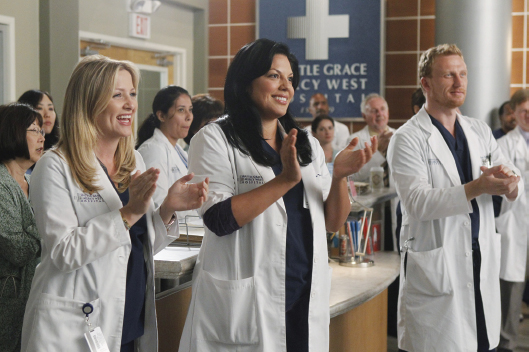

THE GREY’S ANATOMY surgeons spend so much time at Seattle Grace Mercy West Hospital that their work life is their social life—and what results is a complex web of peer relationships. © ABC/Photofest

One of the most fun aspects of watching the television show Grey’s Anatomy is keeping track of the web of relationships among the staff at Seattle Grace Mercy West Hospital. Workplace friendships, secret crushes, full-fledged romances, and bitter resentments could definitely keep your night interesting! Yet these interactions also interest us as scholars because such peer relationships reveal the importance of peer communication, communication between individuals at the same level of authority in an organization. Researchers, management coaches, and popular magazines warn that Americans are spending more and more time in the workplace, leaving less time for outside personal relationships. Yet we all need friends and confidants. So where do we find them? You guessed it—in the organizations we devote time to, particularly the organizations we work for. Research, however, seems to say some contradictory things about whether or not this phenomenon is healthy.

In a survey of more than five million workers over thirty-five years, 29 percent of employees say that they have a “best friend” at work (Jones, 2004). This statistic matters: out of the approximately three in ten people who state that they have a best friend at work, 56 percent are engaged with, or enjoy, their work, whereas 33 percent are not engaged. Only 11 percent are actively disengaged and negative about their work experience. On the other hand, of the seven in ten workers who do not have a best friend at work, only 8 percent are engaged, whereas 63 percent are not. The remaining third of employees without a workplace best friend are actively disengaged from their work (Gallup, cited in Jones, 2004). These findings have powerful implications for employers: having a workplace best friend makes workers seven times more likely to enjoy their work and consequently be more productive. Perhaps this is the thinking behind organizational initiatives to help employees get to know one another—office picnics, hospital softball teams, and school Frisbee and golf tournaments.

When communicating with peers in organizations, remember communication privacy management (Chapter 7), which helps you understand how people perceive and manage personal information. You may decide that certain topics, such as your romantic life, are off-limits at work. You must determine for yourself what is private in different relationships—and it’s also wise to consider the cultural expectations of your organization before sharing.

But there’s also a potential downside to these workplace intimacies. One is that the relationships may not actually be so intimate after all. Management Today warns that professional friendships are often based on what is done together in the workplace. Although that may be beneficial for finding personal support on work-related issues, the friendship can easily wither and die when the mutual experience of work is taken away (“Office Friends,” 2005). Privacy and power also come into play, since sharing personal details about your life can influence how others see you in a professional setting. For example, Pamela, an insurance broker from Chicago, did not want her colleagues or boss to know that she was heading into the hospital to have a double mastectomy in order to avoid breast cancer. But she did tell her close friend and colleague, Lisa. When Pamela returned to the office, there was a “get well soon” bouquet of flowers from her boss waiting on her desk. Lisa had blabbed; Pamela felt betrayed and had the additional burden of her colleagues’ knowing this private, intimate detail about her life (Rosen, 2004). It’s also important to remember that friendships in the workplace—and all organizations—are going to face trials when loyalty and professional obligations are at odds.

Please don’t take this to be a warning against making friends in the organizations to which you belong. Relationships with colleagues and other organizational members can be both career enhancing and personally satisfying; many workplace friendships last long after one or both friends leave a job. But it’s important to be mindful as you cultivate such relationships. The following tips can help (Rosen, 2004):

- Take it slow. When you meet someone new in your organization (be it your job or your residence hall association), don’t blurt out all of your personal details right away. Take time to get to know this potential friend.

- Know your territory. Organizations have different cultures, as you’ve learned. Keep that in mind before you post pictures of your romantic partner all over your gym locker for the rest of the soccer team to see.

- Accept an expiration date. Sometimes friendships simply don’t last outside of the context in which they grew. You may have found that you lost some of your high school friends when you started college; this point is also particularly true for friendships on the job. Accept that life sometimes works out this way and that no one is to blame.

AND YOU?

Question

Who are your three closest friends? Are they members of any organizations that you belong to? If so, has your joint membership affected the friendship in any particularly positive or negative ways? Explain your answer.