13

Organizing, Writing, and Outlining Presentations

LearningCurve can help you master the material in this chapter. Go to the LearningCurve for this chapter.

The Constitution of the United States of America makes a simple demand of the president. “He shall from time to time give to the Congress Information of the State of the Union, and recommend to their Consideration such Measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient” (art. 2, sec. 3).

chapter outcomes

After you have finished reading this chapter, you will be able to

- Organize and support your main points

- Choose an appropriate organizational pattern for your speech

- Move smoothly from point to point

- Choose appropriate and powerful language

- Develop a strong introduction, a crucial part of all speeches

- Conclude with the same strength as in the introduction

- Prepare an effective outline

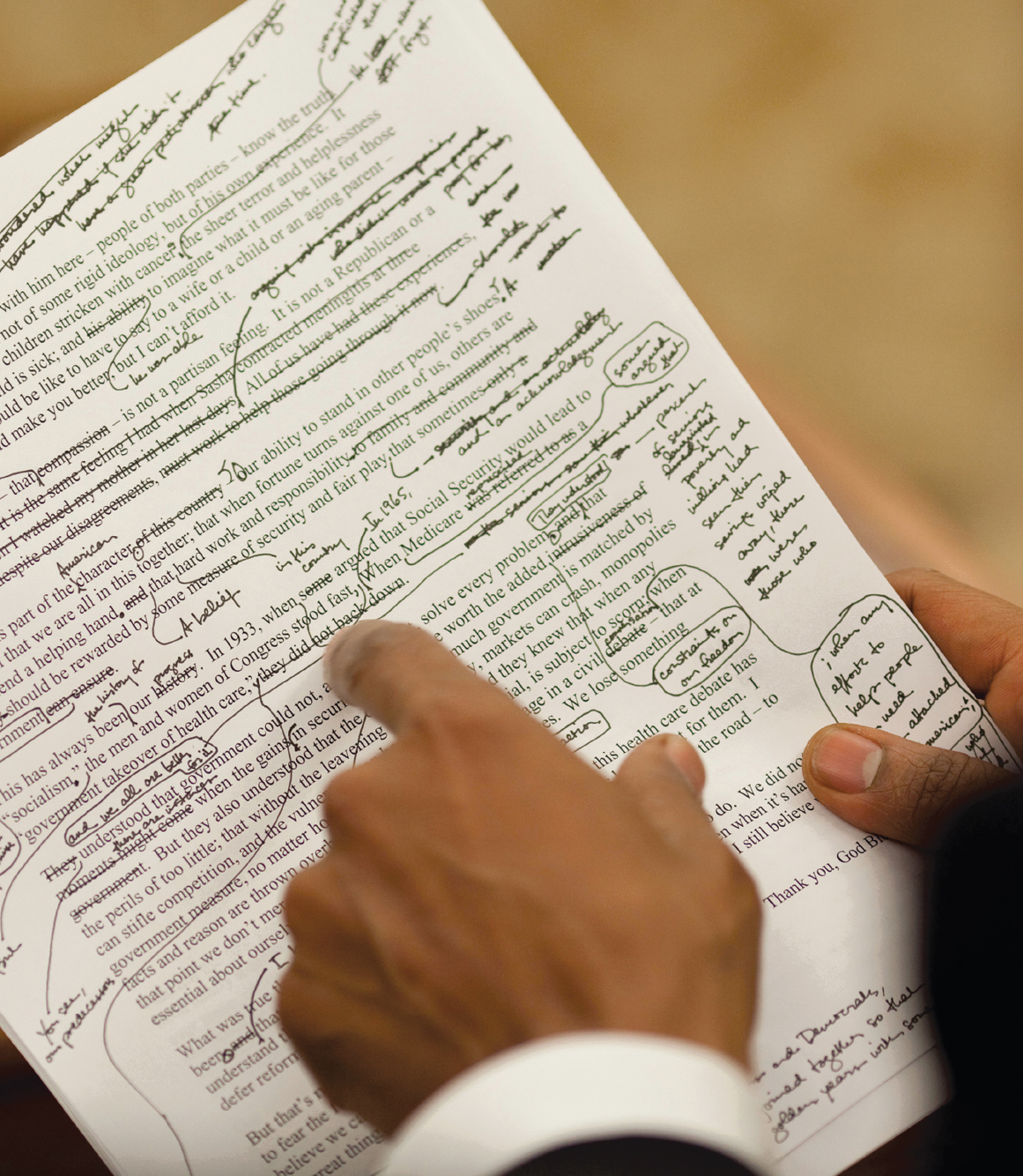

For much of our nation’s history, the State of the Union address was a lengthy letter to Congress read to members of the Senate and House by a congressional clerk. But over time it has evolved into an elaborate and highly politicized annual affair that allows the president to present major ideas and issues directly to the public: the Monroe Doctrine (James Monroe, 1823), the Four Freedoms (Franklin D. Roosevelt, 1941), the War on Terror (George W. Bush, 2002), and the economic overhaul (Barack Obama, 2013) were all detailed for the American people during State of the Union addresses (Amadeo, 2013; Longley, 2007).

And so each January, White House speechwriters face the daunting task of addressing both Congress and the nation with a speech that outlines what is going on in foreign and domestic policy in a way that flatters the president and garners support for his agenda for the following year. To make the task even more difficult, speechwriters must also navigate a deluge of requests from lobbyists, political consultants, and everyday citizens eager to get their pet project, policy, or idea into the president’s speech. “Everybody wants [a] piece of the action,” lamented former White House speechwriter Chriss Winston. “The speechwriter’s job is to keep [the speech] on broad themes so it doesn’t sink of its own weight.” Matthew Scully (2005), one of President George W. Bush’s speechwriters, concurred: “The entire thing can easily turn into a tedious grab bag of policy proposals.”

Imagine that you are building a bridge, a skyscraper, or even a house. You might have ambitious blueprints, but before you can build it, you need to form a solid foundation and develop a structurally sound framework. Any architect will tell you that even the most exciting and lofty designs are useless without these two crucial components. Skimp on either one and your structure will crack, shift, or collapse.

Building a speech follows a similar process. Whether you are writing a national address for the president of the United States or a five-