15

Informative Speaking

LearningCurve can help you master the material in this chapter. Go to the LearningCurve for this chapter.

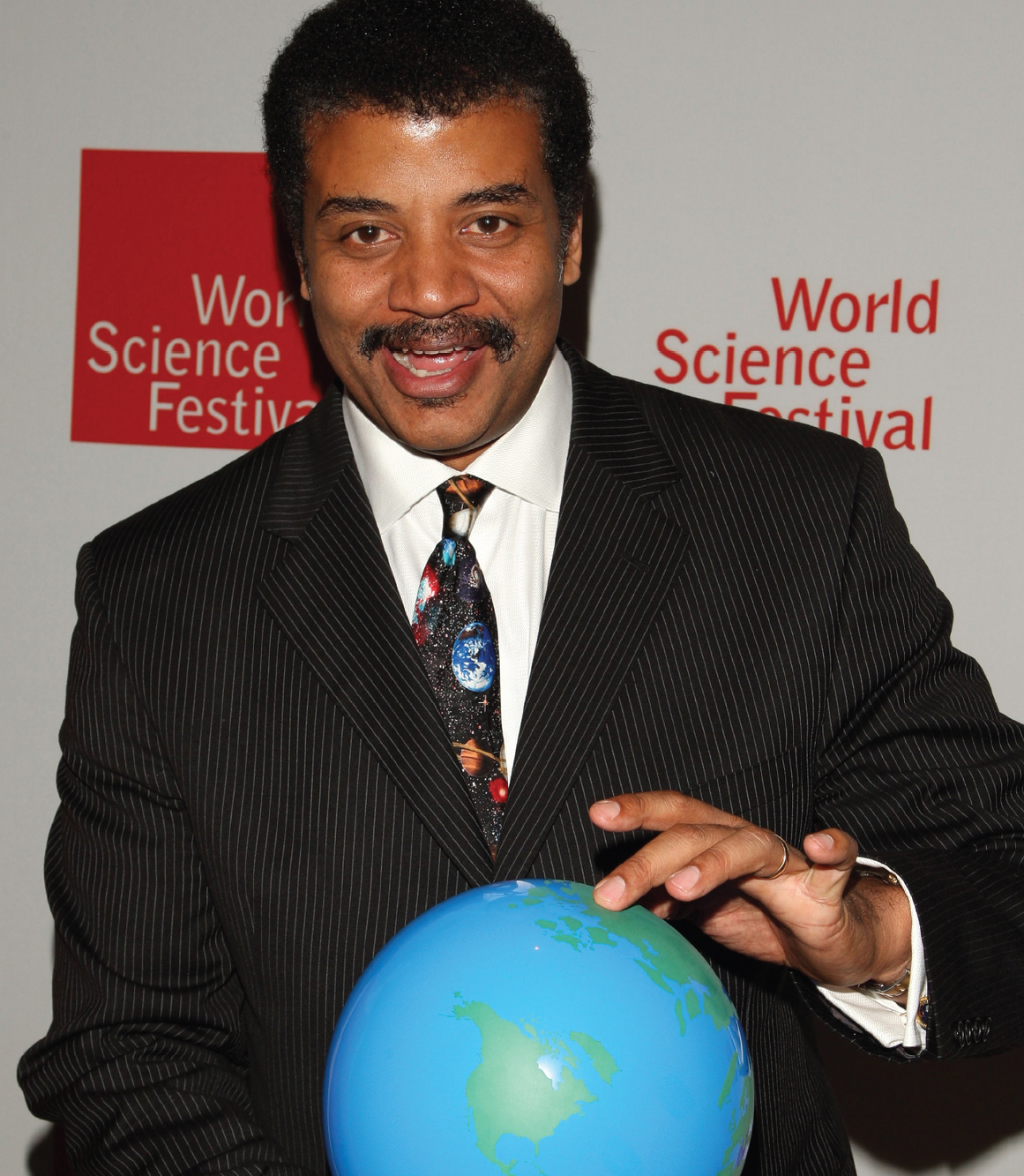

As a noted astrophysicist and the director of the Hayden Planetarium at the American Museum of Natural History, it’s not surprising that people enjoy asking Dr. Neil deGrasse Tyson questions: What happens if you get sucked into a black hole? Why was Pluto demoted to “dwarf planet” status? What is surprising, however, is that people recognize Tyson at all. After all, scientists—

chapter outcomes

After you have finished reading this chapter, you will be able to

- Describe the goals of informative speaking

- List and describe each of the eight categories of informative speeches

- Outline the four major approaches to informative speeches

- Employ strategies to make your audience hungry for information

- Structure your speech to make it easy to listen to

Tyson’s popularity is rooted in both his cosmic expertise and his communication skills, which have been recognized by NASA, the Rotary International, and the science advocacy group EarthSky. He has a particular knack for presenting the vast mysteries of the universe in ways that laypeople can understand. During a presentation at the University of Texas, for example, Tyson noted, “We have no evidence to show whether the universe is infinite or finite,” before explaining that astrophysicists can only go so far to calculate a horizon—

Tyson recognizes the challenge of informing the general public about complex scientific and cosmic issues that researchers devote decades to understanding: “It was not a priority of mine to communicate science to the public,” Tyson says. “What I found was that enough members of the public wanted to know what was going on in the universe that I decided . . . to get a little better at it so I could satisfy this cosmic curiosity” (cited in Byrd, 2010).

Like Neil deGrasse Tyson, the best informative speakers share information, teach us something new, or help us understand an idea. Clearly, Tyson has a talent for informative presentations. He knows how to analyze his audience members and tailor his presentations to engage them quickly. He organizes his information clearly and efficiently so that listeners can learn it with ease. And he presents information in an honest and ethical manner. In this chapter, we’ll take a look at how you can use these same techniques to deliver competent informative speeches in any situation.