Self-Disclosure

The process we use to choose the information we are willing to share with others has long fascinated researchers. In Chapter 7, we examine the social penetration theory, which uses an onion as a metaphor to show how we move from superficial confessions to more intimate ones. Your outer “layer” might consist of disclosure about where you are from, but as you peel away the layers, your disclosures become more personal.

Angelica is a stylish dresser; has a lovely apartment in Austin, Texas; eats out at nice restaurants regularly; and drives a new car. But she has a secret: she is drowning in debt, barely keeping up with her minimum credit card payments. She looks around at her friends, all the same age as she and living similar lifestyles. She wonders if they make more money than she does or if they, too, are over their heads in debt. One night while she’s having coffee with her best friend, Tonya, Angelica comes clean about her situation: she can’t go on their upcoming trip to Cozumel, she tells Tonya, because her credit cards are maxed out.

When you reveal yourself to others by sharing information about yourself—as Angelica has done with Tonya—you engage in self-disclosure. Voluntary self-disclosure functions to develop ordinary social relationships (Antaki, Barnes, & Leudar, 2005) but has more impact or creates more intimacy if it goes below surface information (Tamir & Mitchell, 2012). For example, telling someone that you like snacking on raw vegetables is surface information, but explaining to them why you became a vegetarian is deeper self-disclosure.

Self-disclosure can help you confirm your self-concept or improve your self-esteem; it can also enable you to obtain reassurance or comfort from a trusted friend (Miller, Cooke, Tsang, & Morgan, 1992). For example, Angelica might suspect that Tonya is also living on credit; if Tonya discloses that she is, her confession might reassure Angelica that it’s OK to buy things she can’t afford on credit because everyone else is doing it. However, if Tonya reveals that she makes more money than Angelica, or that she manages her money more wisely, Angelica’s self-concept may incur some damage. As you may remember from Chapter 1, information you receive about your self is termed feedback. The feedback Angelica receives from Tonya will be in response to her self-disclosure. That same feedback—and how she interprets it—will also influence Angelica’s perception of herself.

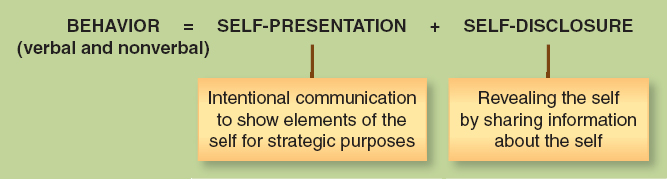

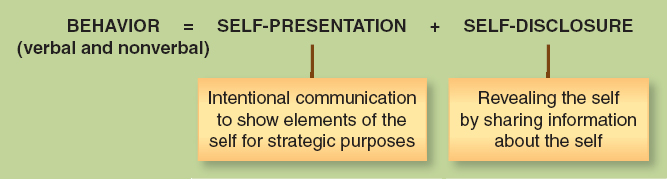

How you incorporate feedback into the self depends on several factors. One of the most important factors is your sensitivity level to feedback. Research demonstrates that some individuals are highly sensitive, whereas others are largely unaffected by the feedback they receive (Edwards, 1990). Presumably, people who are more sensitive to feedback are susceptible and receptive to information about their abilities, knowledge, and talents. Low-sensitive people would be less responsive to such information. For example, when Olympic short track skater Apolo Ohno bombed at the Olympic trials in 1998, he wasn’t interested in hearing that his efforts weren’t sufficient. He was demonstrating a low sensitivity level to the advice and feedback from his coach, friends, and family. Ohno’s father sent him to a secluded cabin for eight days to contemplate his career. After that, Ohno decided that he was ready to receive the feedback that he needed to improve his game. He developed a higher sensitivity to feedback, went on to win eight Olympic medals (Bishop, 2010), and finished the World Championships in the gold, silver, or bronze medal position eighteen times. Figure 2.6 illustrates how self-presentation and self-disclosure constitute the behavior segment of “The Self,” seen in Figure 2.5.

Figure 2.6: FIGURE 2.6 UNDERSTANDING BEHAVIOR