Co-Cultural Communication

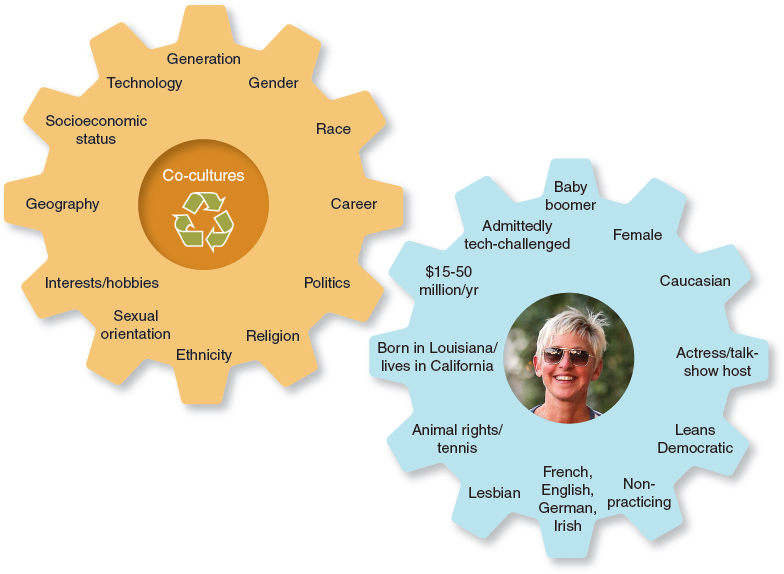

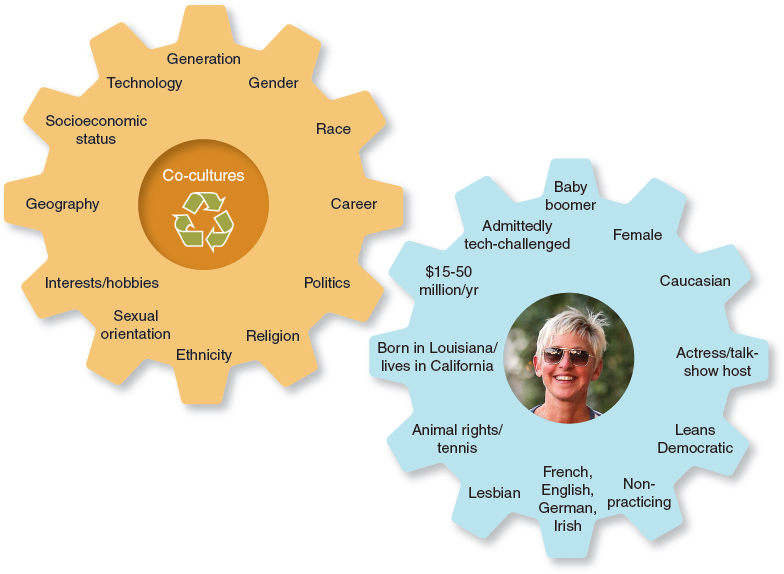

As we discussed in Chapter 1, co-cultures are groups whose members share at least some of the general culture’s system of thought and behavior but have distinct characteristics or attitudes that unify them and distinguish them from the general culture. As you saw in our example about Ellen and as Figure 5.3 shows, ethnic heritage, race (or races), gender, religion, socioeconomic status, and age form just a few of these co-cultures. Other factors come into play as well: some co-cultures are defined by interest, activities, opinions, or by membership in particular organizations (for example, “I am a Republican” or “I am a foodie”).

Figure 5.3: FIGURE 5.3 THE MULTIFACETED NATURE OF CO-CULTURES

Figure 5.3: Unique co-cultures, changing in importance in different situations

Our communication is intrinsically tied to our co-cultural experience. For example, a generation is a group of people who were born during a specific time frame and whose attitudes and behavior were shaped by that time frame’s events and social changes. Generations develop different ideas about how relationships work, ideas that affect communication within and between generations (Howe & Strauss, 1992). For example, Americans who lived through the Second World War share common memories (the bombing of Pearl Harbor, military experience, home-front rationing) that have shaped their worldviews in somewhat similar—though not identical—ways. This shared experience affects how they communicate, as shown in Table 5.2.

Table : TABLE 5.2 GENERATIONS AS CO-CULTURE

| Generation |

Year Born |

Characteristics Affecting Communication |

| Matures |

Before 1946 |

Born before the Second World War, these generations lived through the Great Depression and the First World War. They are largely conformist with strong civic instincts. |

| Baby Boomers |

1946–1964 |

The largest generation, products of an increase in births that began after the Second World War and ended with the introduction of the birth control pill. In their youth, they were antiestablishment and optimistic about the future, but recent surveys show they are more pessimistic today than any other age group. |

| Generation X |

1965–1980 |

Savvy, entrepreneurial, and independent, this generation witnessed the fall of the Berlin Wall and the rise of home computing. |

| Millenials |

1981–2000 |

The first generation of the new millennium, this group includes people under 30, the first generation to fully integrate computers into their everyday communication. |

| Pluralist |

2001–Current |

These digital natives were born into a media-rich, networked world of infinite possibilities that enables them to use digital tools for engagement, learning, creativity, and empowerment. They are the most diverse of any generation and are more likely to have social circles that include people from different ethnic groups, races, and religions. |

Source: Taylor & Keeter, 2010; Horovitz, 2012.

[Click here to open Table 5.2 in a supplemental window]

Similarly, the interplay between our sex and our gender exerts a powerful influence on our communication. Sex refers to the biological characteristics (that is, reproductive organs) that make us male or female, whereas gender refers to the behavioral and cultural traits assigned to our sex; it is determined by the way members of a particular culture define notions of masculinity and femininity (Wood, 2008, 2011). Recall from Chapter 3, for example, that we can use differences in our language styles to express differences in gender identity (Tannen, 2009, 2010).

So, are we destined to live our lives bound by the communication norms and expectations for our sex or gender, our generation, our profession, our hobbies, and our other co-cultures? Hardly. Recall the concept of behavioral flexibility discussed in Chapter 1. This concept notes that competent communicators adapt their communication skills to a variety of life situations. There are contexts and relationships that call for individuals of both sexes to adhere to a more feminine mode of communication (for example, comforting a distraught family member), whereas other contexts and relationships require individuals to communicate in a more masculine way (for example, using direct and confident words when negotiating for a higher salary). Similarly, a teenager who feels most comfortable communicating with others via text messaging or Facebook might do well to send Grandma a handwritten thank-you note for a graduation gift.

In addition, there is a great diversity of communication behaviors within co-cultures (as well as diversity within larger cultures). For example, your grandmother and your best friend’s grandmother may not communicate in the exact same style simply because they are both women, they were born in the same year, or they were both college graduates who became high school English teachers. Similarly, the group typically defined as African Americans includes Americans with a variety of cultural and national heritages. For some, their story stretches back to colonial times; others are more recent immigrants from Africa, the Caribbean, and elsewhere (“Census,” 2010). Christians include a wealth of different denominations that practice various aspects of the larger faith differently. Christians also hail from different races and ethnicities, socioeconomic statuses, regions, political views, and so on. All of these intersecting factors affect communication within any given co-culture.

AND YOU?

Question

Do you consider yourself more of a masculine or feminine individual? (Note that your choice may not align with your biological sex.) Do others communicate with you in ways that support or criticize this aspect of your communication?