Competitive Styles

If you decide that you want the pie more than you want to avoid fighting with your sister, you might demand the entire piece for yourself, at your sister’s expense. Such competitive styles promote the objectives of the individual who uses them rather than the desires of the other person or the relationship.

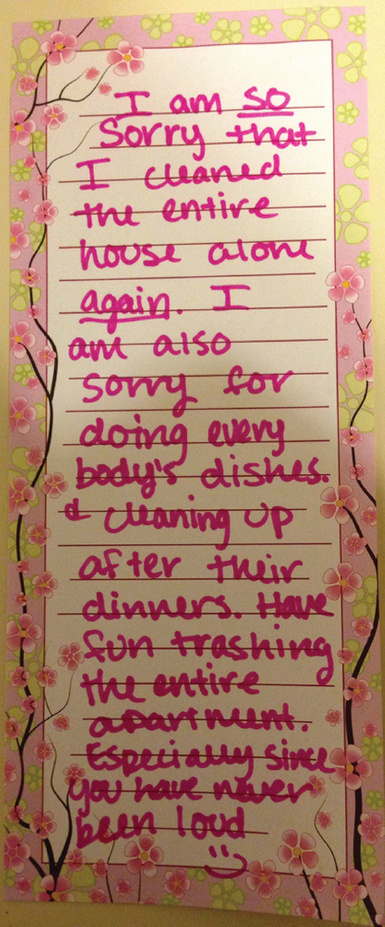

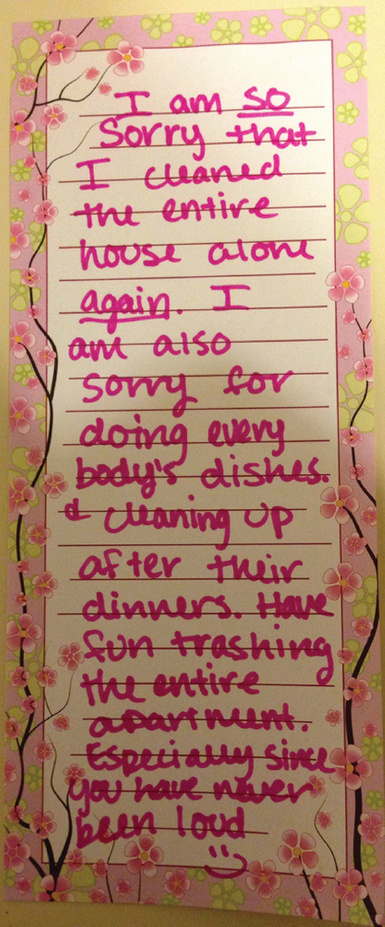

AN HONEST, face-to-face discussion about apartment cleanup and chores is a much better way to solve this problem—chances are this note only made roommate relations worse. Reprinted by Permission © 2014 by Kerry Miller. Used by Permission. All rights reserved

Engaging openly in competition is direct fighting (also known as dominating or competitive fighting). Direct fighters see conflicts as “win or lose” battles—for me to win, you must necessarily lose. Winning arguments involves being assertive—voicing your positions with confidence, defending your arguments, and challenging the arguments of your opposition. Direct fighters are often effective at handling conflicts because they don’t let negative emotions like anxiety, guilt, or embarrassment get in the way, and they stand up for what they believe is right. For example, people tend to openly challenge others when they feel the need to defend themselves from a perceived threat (Canary, Cunningham, & Cody, 1988). This would be a valuable strategy if the friend you came to a party with attempts to get behind the wheel of a vehicle after consuming alcohol. Drunk driving is a threat to your own, your friend’s, and the public’s well-being, and you would probably be well-served to assert yourself competitively in this situation.

On the other hand, the direct fighting style has its downside, particularly for close relationships (Guerrero, Andersen, & Afifi, 2013). Part of the problem is that direct fighting often involves tactics that can be hurtful, such as threats, name-calling, and criticism. What begins as assertiveness can quickly move to verbal aggressiveness—attacking the opposing person’s self-concept and belittling the other person’s needs. For example, if you were to rudely assert to your sister “You’re so fat—I would think you’d want to avoid pie,” you may end up “winning” the pie, but you may well damage your bond with your sister. Indeed, research finds that parents’ verbal aggression toward their children can negatively impact relationship satisfaction and is associated with nonsecure attachment styles among young adults (Roberto, Carlyle, Goodall, & Castle, 2009). When verbal aggression is used by supervisors toward their subordinates in the workplace, it can also negatively affect employee job satisfaction and commitment (Madlock & Kennedy-Lightsey, 2010).

Competition doesn’t always involve being openly assertive or aggressive. Many competitors instead use a “passive” style of aggression known as indirect fighting (Sillars, Canary, & Tafoya, 2004). Your sister might hide the pie so that you cannot find it, or she might leave a nasty note next to it saying “my germs are on this.” With indirect fighting, people often want you to know that they are upset and try to get you to change your behavior, but they are unwilling to face the issue with you openly. In most situations, passive-aggressive behaviors come across as hostile and ineffective and usually end up being destructive to relationships. Studies have found that indirect fighting is associated with lower relationship commitment in friendships (Allen, Babin, & McEwan, 2012), reduced satisfaction in romantic partnerships (Guerrero, Farinelli, & McEwan, 2009), and even long-term distress in marriage (Kilmann, 2012).