1.1.2 Understanding Communication Models

Printed Page 8

Understanding Communication Models

Think about all the different ways you communicate each day. You text-message your sister, excitedly announcing that you got the job you wanted. You give a speech in your communication class, acting more animated when you see your audience’s attention start to wane. You exchange a knowing glance with your best friend when a person you both dislike boasts about his latest romantic conquest. Now reflect on how these forms of communication differ from each other. Sometimes (like when text-messaging), you create messages and send them to receivers, the messages flowing in a single direction from origin to destination. In other instances (like when speaking in front of your class), you present messages to recipients, and the recipients signal to you that they’ve received and understood them. Still other times (like when you and your best friend exchange a glance), you mutually construct meanings with others, with no one serving as “sender” or “receiver.” These different ways of experiencing communication are reflected in three models that have evolved to describe the communication process: the linear model, the interactive model, and the transactional model. As you will see, each of these models has both strengths and weaknesses. Yet each also captures something unique and useful about the ways you communicate in your daily life.

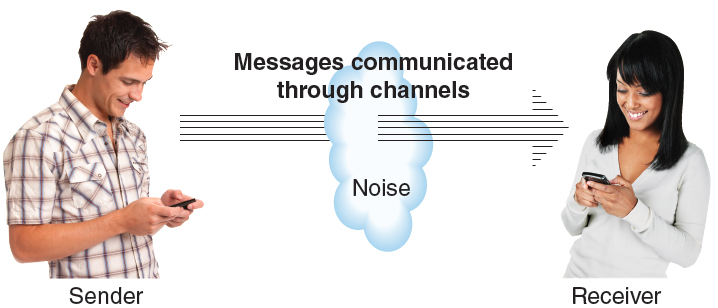

Linear Communication Model According to the linear communication model, communication is an activity in which information flows in one direction, from a starting point to an end point (see Figure 1.2). The linear model contains several components (Lasswell, 1948; Shannon & Weaver, 1949). In addition to a message and a channel, there must be a sender (or senders) of the message—the individual(s) who generates the information to be communicated, packages it into a message, and chooses the channel(s) for sending it. There also is noise—factors in the environment that impede messages from reaching their destination. Noise includes anything that causes our attention to drift from messages—such as poor reception during a cell-phone call or the smell of fresh coffee nearby. Last, there must be a receiver: the person for whom a message is intended and to whom the message is delivered.

Noise

Watch this clip to answer the questions below.

Question

Want to see more? Check out the Related Content section for additional clips on channel and linear communication model.

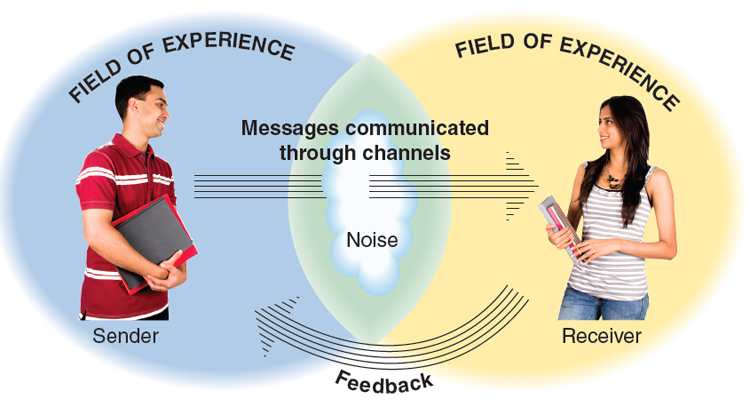

Interactive Communication Model The interactive communication model also views communication as a process involving senders and receivers (see Figure 1.3). However, according to this model, transmission is influenced by two additional factors: feedback and fields of experience (Schramm, 1954). Feedback is comprised of the verbal and nonverbal messages that recipients convey to indicate their reaction to communication. Whether it’s eye contact, utterances such as “uh-huh” and “that’s right,” or nodding, receivers deliver feedback to let senders know they’ve received and understood the message and to indicate their approval or disapproval. Fields of experience consist of the beliefs, attitudes, values, and experiences that each participant brings to a communication event. People with similar fields of experience are more likely to understand each other while communicating than are individuals with dissimilar fields of experience.

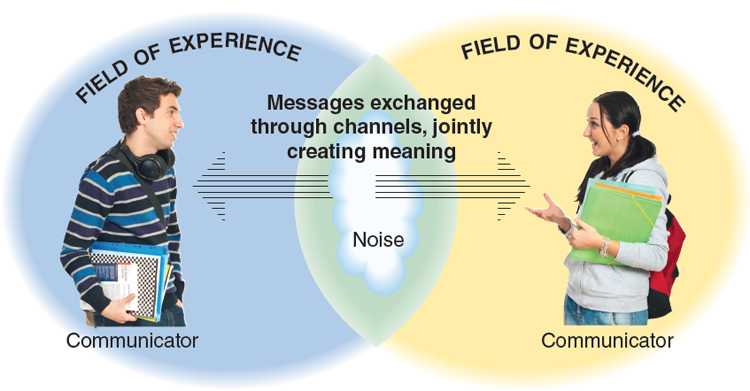

Transactional Communication Model The transactional communication model (see Figure 1.4) suggests that communication is fundamentally multidirectional. That is, each participant equally influences the communication behavior of the other participants (Miller & Steinberg, 1975). From the transactional perspective, there are no “senders” or “receivers.” Instead, all the parties constantly exchange verbal and nonverbal messages and feedback, collaboratively creating meanings (Streek, 1980). This may be something as simple as a shared look between friends, or it may be an animated conversation among close family members in which the people involved seem to know what the others are going to say before it’s said.

Transactional Communication Model

Watch this clip to answer the questions below.

Question

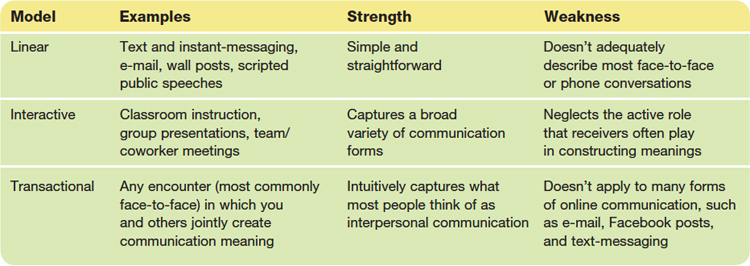

These three models represent an evolution of thought regarding the nature of communication, from a relatively simplistic depiction of communication as a linear process to one that views communication as a complicated process that is mutually crafted. However, these models don’t necessarily represent “good” or “bad” ways of thinking about communication. Instead, each of them is useful for thinking about different forms of communication. See Table 1.1 below for more on each model.

Table 1.1 Communication Models