2.4.3 Your Hidden And Revealed Self

Printed Page 60

Your Hidden and Revealed Self

The image of self and relationship development offered by social penetration theory suggests a relatively straightforward evolution of intimacy, with partners gradually penetrating broadly and deeply into each other’s selves over time. But in thinking about our selves and our relationships with others, two important questions arise: First, are we really aware of all aspects of ourselves? Second, are we willing to grant others access to all aspects of ourselves?

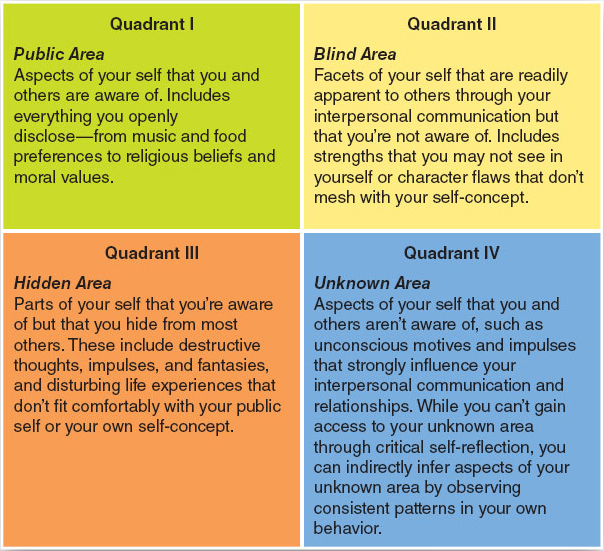

We can explore possible answers to these questions by looking at the model of the relational self called the Johari Window, named after the psychologists who developed it, Joe Luft and Harry Ingham (Luft, 1970). The Johari Window (see Figure 2.3 below) suggests that some “quadrants” of our selves are open to self-reflection and sharing with other people, while others remain hidden—to both ourselves and others.

Importantly, as our interpersonal relationships develop and we increasingly share previously hidden information with our partners, our unknown and blind quadrants remain fairly stable. By their very nature, our unknown areas remain unknown throughout much of our lives. And for most of us, the blind area remains imperceptible. That’s because our blind areas are defined by our deepest-rooted beliefs about ourselves—those beliefs that make up our self-concepts. Consequently, when others challenge us to open our eyes to our blind areas, we resist.

During the early stages of an interpersonal relationship and especially during first encounters, our public area of self is much smaller than our hidden area. As relationships progress, partners gain access to broader and deeper information about their selves; consequently, the public area expands and the hidden area diminishes. The Johari Window thus provides us with a useful alternative metaphor to social penetration. As relationships develop, we don’t just let people “penetrate inward” to our central selves; we let them “peer into” more parts of our selves by revealing information that we previously hid from them.

Question

To improve our interpersonal communication, we must be able to see into our blind areas and then change the aspects within them that lead to incompetent communication and relationship challenges. But this isn’t easy. After all, how can you correct misperceptions about yourself that you don’t even know exist or flaws that you consider your greatest strengths? Delving into your blind area means challenging fundamental beliefs about yourself—subjecting your self-concept to hard scrutiny. Your goal is to overturn your most treasured personal misconceptions. Most people accomplish this only over a long period of time and with the assistance of trustworthy and willing relationship partners.