3.2.4 Personality

Printed Page 89

Personality

When you think about the star of a hit television show, a cartoon aardvark isn’t usually the first thing to come to mind. But, as any one of the 10 million weekly viewers of PBS’s Arthur will tell you, the appeal of the show is more than just the title character. It is the breadth of personalities displayed across the entire cast, allowing us to link each of them to people in our own lives. Sue Ellen loves art, music, and world culture, while the Brain is studious, meticulous, and responsible. Francine loves interacting with people, especially while playing sports, and Buster is laid-back, warm, and friendly to just about everyone. D.W. drives Arthur crazy with her moods, obsessions, and tantrums; while Arthur—at the center of it all—combines all of these traits into one appealing, complicated package.

In the show Arthur, we see embodied in animated form the various dispositions that populate our real-world interpersonal lives. And when we think of these people and their personalities, visceral reactions are commonly evoked. We like, loathe, or even love people based on our perception of their personalities and how their personalities mesh with our own.

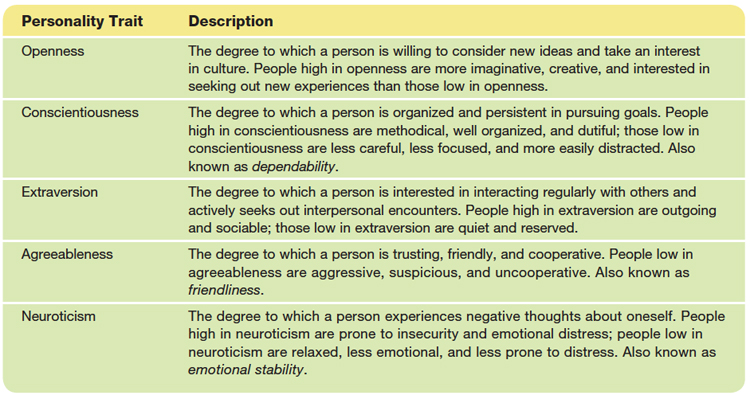

Clearly, personality shapes how we perceive others, but what exactly is it? Personality is an individual’s characteristic way of thinking, feeling, and acting, based on the traits—enduring motives and impulses—that he or she possesses (McCrae & Costa, 2001). Contemporary psychologists argue that although thousands of different personalities exist, each is comprised of only five primary traits, referred to as the “Big Five” (John, 1990). These are openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism (see Table 3.2 below). A simple way to remember them is the acronym OCEAN. Alternatively, you can think Sue Ellen, the Brain, Francine, Buster, and D.W.! The degree to which a person possesses each of the Big Five traits determines his or her personality (McCrae, 2001).

Prioritizing Our Own Traits When Perceiving Others Our perception of others is strongly guided by the personality traits we see in ourselves and how we evaluate these traits. If you’re an extravert, for example, another person’s extraversion becomes salient to you when you’re communicating with him or her. Likewise, if you pride yourself on being friendly, other people’s friendliness becomes your perceptual focus.

Table 3.2 The Big Five Personality Traits (OCEAN)

But it’s not just a matter of focusing on certain traits to the exclusion of others. We evaluate people positively or negatively in accordance with how we feel about our own traits. We typically like in others the same traits we like in ourselves, and we dislike in others the traits that we dislike in ourselves.

To avoid this preoccupation with your own traits, carefully observe how you focus on other people’s traits and how your evaluation of these traits reflects your own feelings about yourself. Strive to perceive people broadly, taking into consideration all of their traits and not just the positive or negative ones that you share. Then evaluate them and communicate with them independently of your own positive and negative self-evaluations.

Question

Generalizing from the Traits We Know Another effect that personality has on perception is the presumption that because a person is high or low in a certain trait, he or she must be high or low in other traits. For example, say that I introduce you to a friend of mine, Shoshanna. Within the first minute of interaction you perceive her as highly friendly. Based on your perception of her high friendliness, you’ll likely also presume that she is highly extraverted, simply because high friendliness and high extraversion intuitively seem to “go together.” If people you’ve known in the past who were highly friendly and extraverted also were highly open, you may go further, perceiving Shoshanna as highly open as well.

Your perception of Shoshanna was created using implicit personality theories, personal beliefs about different types of personalities and the ways in which traits cluster together (Bruner & Taguiri, 1954). When we meet people for the first time, we use implicit personality theories to perceive just a little about an individual’s personality and then presume a great deal more, making us feel that we know the person and helping to reduce uncertainty. At the same time, making presumptions about people’s personalities is risky. Presuming that someone is high or low in one trait because he or she is high or low in others can lead you to communicate incompetently. For example, if you presume that Shoshanna is high in openness, you might mistakenly presume she has certain political or cultural beliefs, leading you to say things to her that cut directly against her actual values such as “Don’t you just hate when people mix religion and politics?” However, Shoshanna might respond with “No, actually I think that government should be based on scriptural principles.”