3.3 FORMING IMPRESSIONS OF OTHERS

Printed Page 92

Forming Impressions of Others

Perception creates impressions that may evolve over time

When we use perception to size up other people, we form interpersonal impressions—mental pictures of who people are and how we feel about them. All aspects of the perception process shape our interpersonal impressions: the information we select as the focus of our attention, the way we organize this information, the interpretations we make based on knowledge in our schemata and our attributions, and even our uncertainty.

Given the complexity of the perception process, it’s not surprising that impressions vary widely. Some impressions come quickly into focus. We meet a person and take an immediate dislike to him. Or we quickly decide that someone’s a “fun person” after chatting with her briefly. Other impressions form slowly, over a series of encounters. Some impressions are intensely positive, others neutral, and still others negative. But regardless of their form, interpersonal impressions exert a profound impact on our communication and relationship choices. To illustrate this impact, imagine yourself in the following situation.

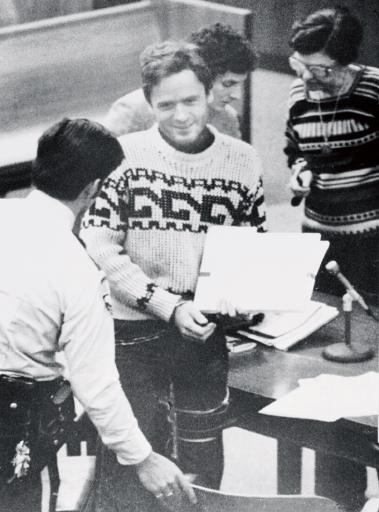

It’s summer, and you’re at a lake, hanging out with friends. As you lie on the beach, the man pictured in the photo below approaches you. He introduces himself as “Ted” and tells you that he’s waiting for some friends who were supposed to help him load his sailboat onto his car. He’s easy to talk to, friendly, and has a nice smile. His left arm is in a sling, and he casually mentions that he injured it playing racquetball. Because his arm is hurting, and his friends are missing, he asks if you would help him with his boat. You say, “Sure.” You walk with him to the parking lot, but when you get to Ted’s car, you don’t see a boat. When you ask him where his boat is, he says, “Oh! It’s at my folks’ house, just up the hill. Do you mind going with me? It’ll just take a couple of minutes.” You tell him you can’t go with him because your friends will wonder where you are. “That’s OK,” Ted says cheerily, “I should have told you it wasn’t in the parking lot. Thanks for bothering anyways.” As the two of you walk back to the beach, Ted repeats his apology and expresses gratitude for your willingness to help him. He’s polite and strikes you as sincere.

Think about your encounter with Ted, and all that you’ve perceived. What’s your impression of him? What traits besides the ones you’ve observed would you expect him to have? What do you predict would have happened if you had gone with him to his folks’ house to help load the boat? Would you want to play racquetball with him? Would he make a good friend? Does he interest you as a possible romantic partner?

The scenario you’ve read actually happened. The above description is drawn from the police testimony of Janice Graham, who was approached by Ted at Lake Sammamish Park, near Seattle, Washington, in 1974 (Michaud & Aynesworth, 1989). Graham’s decision not to accompany Ted saved her life. Two other women—Janice Ott and Denise Naslund—were not so fortunate. Each of them went with Ted, who raped and murdered them. Friendly, handsome, and polite Ted was none other than Ted Bundy, one of the most notorious serial killers in U.S. history.

Thankfully, most of the interpersonal impressions we form don’t have life-or-death consequences. But all impressions do exert a powerful impact on how we communicate with others and whether we pursue relationships with them. For this reason, it’s important to understand how we can flexibly adapt our impressions to create more accurate and reliable conceptions of others.