3.1.2 Organizing The Information You've Selected

Printed Page 77

Organizing the Information You’ve Selected

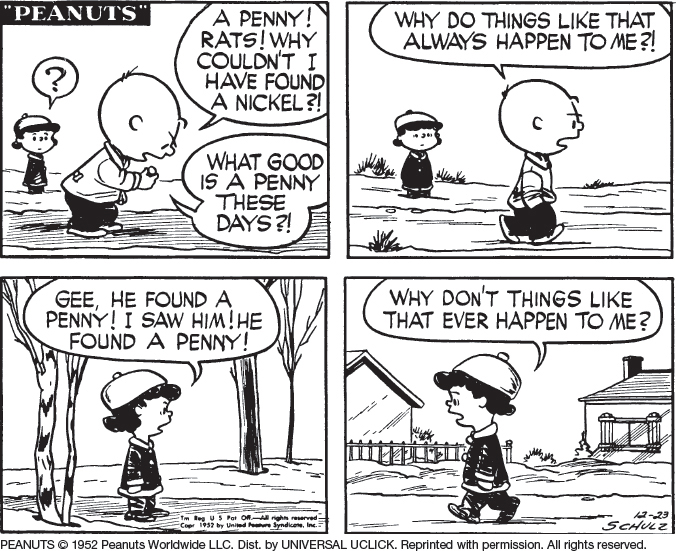

Once you’ve selected something as the focus of your attention, you take that information and structure it into a coherent pattern inside your mind, a phase of the perception process known as organization (Fiske & Taylor, 1991). For example, imagine that a cousin is telling you about a recent visit to your hometown. As she shares her story with you, you select certain bits of her narrative on which to focus your attention based on salience, such as a mutual friend she saw during her visit or a favorite old hangout she saw. You then organize your own representation of her story inside your head.

During organization, you engage in punctuation, structuring the information you’ve selected into a chronological sequence that matches how you experienced the order of events (Watzlawick, Beavin, & Jackson, 1967). You determine which words and actions occurred first, second, and so on, and which comments or behaviors caused subsequent actions to occur. To illustrate punctuation, think about how you might punctuate the sequence of events in our housemate example. You hear a noise, open your eyes, see your housemate in your room, and then hear her yelling at you. But two people involved in the same interpersonal encounter may punctuate it in very different ways. Here’s how your housemate might punctuate the same incident:

I was in my room studying for finals, but my cell phone kept ringing. I got so irritated that I turned my phone off. But then my housemate’s cell phone rang. I yelled for him to get it, but the phone kept ringing. I ran out to the kitchen and grabbed his phone. I shouted outside his door, “Your phone is ringing,” but he didn’t respond. I blew up, charged into his room, and found him there with his headphones on, listening to music. I said, “I’ve been yelling at you to pick up your phone for the last five minutes! What’s going on?”

Punctuation

Watch this clip to answer the questions below.

Question

If you and another person organize and punctuate information from an encounter differently, the two of you may well feel frustrated with one another. Disagreements about punctuation, and especially disputes about who “started” unpleasant encounters, are a common source of interpersonal conflict (Watzlawick et al., 1967). For example, your housemate may contend that “you started it” because she told you to get your phone but you ignored her. You may believe that “she started it” because she barged into your room without knocking.

Question

We can avoid perceptual misunderstandings that lead to conflict by understanding how our organization and punctuation of information differ from those of other people. For instance, if you asked your housemate why she was yelling at you and learned that she thought you were ignoring her, you might realize that she wasn’t interrupting your study break just to be annoying. And if she asked why you didn’t get your phone and learned that you didn’t hear her, her frustration might dissipate as well. One helpful way to forestall such conflicts is to practice asking others to share their views of encounters. You might say, “Here’s what I saw, but that’s just my perspective. What do you think happened?”