3.1.3 Interpreting The Information

Printed Page 78

Interpreting the Information

As we organize information we have selected into a coherent mental model, we also engage in interpretation, assigning meaning to that information. We call to mind familiar information that’s relevant to the current encounter, and we use that information to make sense of what we’re hearing and seeing. We also create explanations for why things are happening as they are.

Using Familiar Information We make sense of others’ communication in part by comparing what we currently perceive with knowledge that we already possess. For example, I proposed to my wife by surprising her after class. I had decorated her apartment with several dozen roses and carnations, was dressed in my best (and only!) suit, and was spinning “our song” on her turntable—the Spinners’ “Could It Be I’m Falling in Love.” When she opened the door, and I asked her to marry me, she immediately interpreted my communication correctly. But how, given that she never had been proposed to before? Because she knew from friends, family members, movies, and television shows what a marriage proposal looks and sounds like. Drawing on this familiar information, she correctly figured out what I was up to and (thank goodness!) accepted my proposal.

The knowledge we draw on when interpreting interpersonal communication resides in schemata, mental structures that contain information defining the characteristics of various concepts, as well as how those characteristics are related to each other (Macrae & Bodenhausen, 2001). Each of us develops schemata for individual people, groups of people, places, events, objects, and relationships. In the example above, my wife had a schemata for “marriage proposal,” and that enabled her to correctly interpret my actions.

Because we use familiar information to make sense of current interactions, our interpretations reflect what we presume to be true. For example, suppose you’re interviewing for a job with a manager who has been at the company for 18 years. You’ll likely interpret everything she says in light of your knowledge about “long-term employees.” This knowledge includes your assumption that “company veterans generally know insider information.” So, when your interviewer talks in glowing terms about the company’s future, you’ll probably interpret her comments as credible. Now imagine that you’re interviewing with someone who has been with the company only a few weeks. Although he may present the exact same message to you about the company’s future, you’ll probably interpret his comments differently. Based on your perception of him as “new employee,” and on the information you have in your “new employee” schema, you may interpret his message as naïve speculation rather than “expert commentary”—even if his statements are accurate.

Creating Explanations In addition to drawing on our schemata to interpret information from interpersonal encounters, we create explanations for others’ comments or behaviors, known as attributions. Attributions are our answers to the “why” questions we ask every day. “Why didn’t my partner return my text message?” “Why did my best friend post that horrible, embarrassing photo of me on Facebook?”

Consider an example shared with me by a friend of mine, Sarah. She had finished teaching for the semester and was visiting her mother, who lived out-of-state. A student of hers, whom we’ll call “Janet,” had failed her course. During the time Sarah was out of town, Janet e-mailed to ask if there was anything she could do to change her grade. However, Sarah was offline for the week and missed Janet’s e-mail. Checking her messages upon her return, she discovered Janet’s original e-mail, along with a second, follow-up message:

From: Janet [mailto:janet@school.edu]

Sent: Tuesday, May 15, 2012 10:46 AM

To: Professor Sarah

Subject: FW: Grade

Maybe my situation isn’t a priority to you, and that’s fine, but a response e-mail would’ve been appreciated! Even if all you had to say was “there’s nothing I can do.” I came to you seeking help, not a hand-out!—Janet.2

Put yourself in Janet’s shoes for a moment. What attributions did Janet make about Sarah’s failure to respond? How did these attributions shape Janet’s communication in her second e-mail? Now consider this situation from Sarah’s perspective. If you were in her shoes, what attributions would you make about Janet, and how would they shape how you interpreted her e-mail?

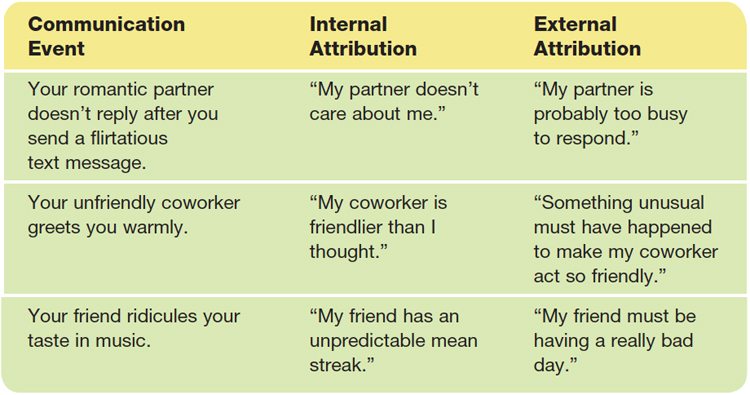

Attributions take two forms, internal and external (see Table 3.3). Internal attributions presume that a person’s communication or behavior stems from internal causes, such as character or personality. For example, “My professor didn’t respond to my e-mail because she doesn’t care about students,” or “Janet sent this message because she’s rude.” External attributions hold that a person’s communication is caused by factors unrelated to personal qualities: “My professor didn’t respond to my e-mail because she hasn’t checked her messages yet,” or “Janet sent this message because I didn’t respond to her first message.”

Like schemata, the attributions we make influence powerfully how we interpret and respond to others’ communication. For example, if you think Janet’s e-mail was caused by her having a terrible day, you’ll likely interpret her message as an understandable venting of frustration. If you think her message was caused by her personal rudeness, you’ll probably interpret the e-mail as inappropriate and offensive.

Given the dozens of people with whom we communicate each day, it’s not surprising that we often form invalid attributions. One common mistake is the fundamental attribution error, the tendency to attribute others’ behaviors solely to internal causes (the kind of person they are) rather than the social or environmental forces affecting them (Heider, 1958). For example, communication scholar Alan Sillars and his colleagues found that during conflicts between parents and teens, both parties fall prey to the fundamental attribution error, making internal attributions about each other’s messages that contribute to escalating the conflict (Sillars, Smith, & Koerner, 2010). Parents commonly attribute teens’ communication to “lack of responsibility” and “desire to avoid the issue” whereas teens attribute parents’ communication to “desire to control my life.” All these assumptions are internal causes. These errors make it harder for teens and parents to constructively resolve their conflicts, something we discuss more in Chapter 8.

Question

The fundamental attribution error is so named because it is the most prevalent of all perceptual biases and each of us falls prey to it (Langdridge & Butt, 2004). Why does this error occur? Because when we communicate with others, they dominate our perception. They—not the surrounding factors that may be causing their behavior—are most salient for us. Consequently, when we make judgments about why someone is acting in a certain way, we overestimate the influence of the person and underestimate the significance of his or her immediate environment (Heider, 1958; Langdridge & Butt, 2004).

The fundamental attribution error is especially common during online interactions (Shedletsky & Aitken, 2004). Because we aren’t privy to the rich array of environmental factors that may be shaping our communication partners’ messages—all we perceive is words on a screen—we’re more likely than everto interpret others’ communication as stemming solely from internal causes (Wallace, 1999). As a consequence, when a text message, Facebook wall post, e-mail, or instant message is even slightly negative in tone, we’re very likely to blame that negativity on bad character or personality flaws. Such was the case when Sarah presumed that Janet was a “rude person” based on her e-mail.

Improving Online Attributions

- Improving your attributions while communicating online

-

Identify a negative text, e-mail, IM, or Web posting you’ve received.

Identify a negative text, e-mail, IM, or Web posting you’ve received. -

Consider why the person sent the message.

Consider why the person sent the message. -

Write a response based on this attribution, and save it as a draft.

Write a response based on this attribution, and save it as a draft. -

Think of and list other possible, external causes for the person’s message.

Think of and list other possible, external causes for the person’s message. -

Keeping these alternative attributions in mind, revisit and reevaluate your message draft, editing it as necessary to ensure competence before you send or post it.

Keeping these alternative attributions in mind, revisit and reevaluate your message draft, editing it as necessary to ensure competence before you send or post it.

A related error is the actor-observer effect, the tendency of people to make external attributions regarding their own behaviors (Fiske & Taylor, 1991). Because our mental focus during interpersonal encounters is on factors external to us—especially the person with whom we’re interacting—we tend to credit these factors as causing our own communication. This is particularly prevalent during unpleasant interactions. Our own impolite remarks during family conflicts are viewed as “reactions to their hurtful communication” rather than “messages caused by our own insensitivity.” Our terseness toward coworkers is seen as “a natural response to incessant work interruptions” rather than “communication resulting from our own prickly personality.”

However, we don’t always make external attributions regarding our own behaviors. In cases where our actions result in noteworthy success, either personal or professional, we typically take credit for the success by making an internal attribution, a tendency known as the self-serving bias (Fiske & Taylor, 1991). Suppose, for example, you’ve successfully persuaded a friend to lend you her car for the weekend—something you’ve never pulled off before. In this case, you will probably attribute this success to your charm and persuasive skill rather than to luck or your friend’s generosity. The self-serving bias is driven by ego protection: by crediting ourselves for our life successes, we can feel happier about who we are.

Clearly, attributions play a powerful role in how we interpret communication. For this reason, it’s important to consider the attributions you make while you’re interacting with others. Check your attributions frequently, watching for the fundamental attribution error, the actor-observer effect, and the self-serving bias. If you think someone has spoken to you in an offensive way, ask yourself if it’s possible that outside forces—including your own behavior—could have caused the problem. Also keep in mind that communication (like other forms of human behavior) rarely stems from only external or internal causes. It’s caused by a combination of both (Langdridge & Butt, 2004).

Finally, when you can, check the accuracy of your attributions by asking people for the reasons behind their behavior. When you’ve made attribution errors that lead you to criticize or lose your patience with someone else, apologize and explain your mistake to the person. After Janet learned that Sarah hadn’t responded because she had been out-of-state—as opposed to intentionally blowing her off—Janet apologized. She also explained why her message was so terse: she thought Sarah was intentionally ignoring her. Upon receiving Janet’s apology, Sarah apologized also. She realized that she, too, had succumbed to the fundamental attribution error: she had wrongly presumed that Janet was rude, when in fact Janet’s frustration over not getting a response was what had caused her to communicate as she did.