4.4.2 Anger

Printed Page 129

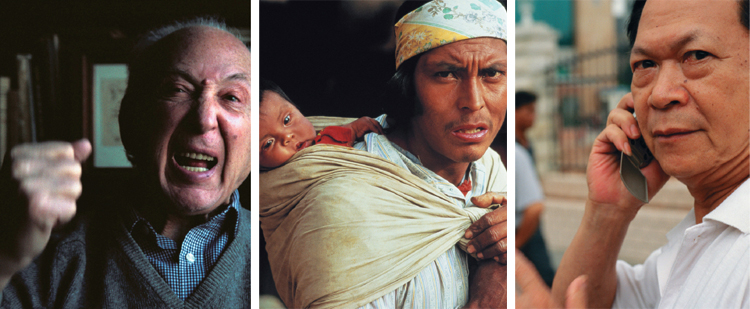

Anger

Anger is a negative primary emotion that occurs when you are blocked or interrupted from attaining an important goal by what you see as the improper action of an external agent (Berkowitz & Harmon-Jones, 2004). As this definition suggests, anger is almost always triggered by someone or something external to us, and is driven by our perception that the interruption is “unfair” (Scherer, 2001). So, for example, when your roommate who is always offering to lend you money refuses to give you a much-needed loan, you’re more likely to feel angry if you think he or she can afford to give you the loan but is simply choosing not to (you decide that your roommate’s behavior is “unjust” given his or her past offers and your current financial standing). By contrast, if you think your roommate is willing but unable to help you (he or she wants to lend you money but has none to give), you’ll be less likely to feel anger toward him or her.

Anger is commonplace: the average person is mildly to moderately angry anywhere from several times a day to several times a week (Berkowitz & Harmon-Jones, 2004). Perhaps because of its frequency, we commonly underestimate anger’s destructive potential. We wrongly presume that we can either suppress it or openly express it and that the damage will be minimal. But anger is our most intense and potentially destructive emotion. For example, anger causes perceptual errors that enhance the likelihood we will respond with verbal or physical violence toward others (Lemerise & Dodge, 1993). Both men and women report the desire to punch, smash, kick, bite, or take similar violent actions toward others when they are angry (Carlson & Hatfield, 1992). The impact of anger on interpersonal communication is also devastating. Angry people are more likely to argue, make accusations, yell, swear, and make hurtful and abusive remarks (Knobloch, 2005). Additionally, passive-aggressive communication such as ignoring others, pulling away, giving people dirty looks, and using the “silent treatment” are all more likely to happen when you’re angry (Knobloch, 2005).

The most frequently used strategy for managing anger is suppression. You “bottle it up” inside rather than let it out. You might pretend that you’re not really feeling angry, blocking your angry thoughts and attempting to control communication of your anger. Occasional suppression can be constructive, such as when open communication of anger would be unprofessional, or when anger has been triggered by mistaken perceptions or attributions. But always suppressing anger can cause physical and mental problems: you put yourself in a near-constant state of arousal and negative thinking known as chronic hostility. People suffering from chronic hostility spend most of their waking hours simmering in a thinly veiled state of suppressed rage. Their thoughts and perceptions are dominated by the negative. They are more likely than others to believe that human nature is innately evil and that most people are immoral, selfish, exploitative, and manipulative. Ironically, because chronically hostile people believe the worst about others, they tend to be difficult, self-involved, demanding, and ungenerous (Tavris, 1989).

A second common anger management strategy is venting: explosively disclosing all of your angry thoughts to whoever triggered them. Many people view venting as helpful and healthy; it “gets the anger out.” The assumption that venting will rid you of anger is rooted in the concept of catharsis, which holds that openly expressing your emotions enables you to purge them. But in contrast to popular beliefs about the benefits of venting, research suggests that while venting may provide a temporary sense of pleasure, it actually boosts anger. One field study of engineers and technicians who were fired from their jobs found that the more individuals vented their anger about the company, the angrier they became (Ebbeson, Duncan, & Konecni, 1975).

To manage your anger, it’s better to use strategies such as encounter avoidance, encounter structuring, and reappraisal. In cases where something or someone has already triggered anger within you, consider using the Jefferson strategy, named after the third president of the United States. When a person says or does something that makes you angry, count slowly to 10 before you speak or act (Tavris, 1989). If you are very angry, count slowly to 100; then speak or act. Thomas Jefferson adopted this simple strategy for reducing his own anger during interpersonal encounters.

Although the Jefferson strategy may seem silly, it’s effective because it creates a delay between the event that triggered your anger, the accompanying arousal and awareness, and your communication response. The delay between your internal physical and mental reactions and your outward communication allows your arousal to diminish somewhat, including lowering your adrenaline, blood pressure, and heart rate. Therefore, you communicate in a less extreme (and possibly less inappropriate) way than if you had not “counted to 10.” A delay also gives you time for critical self-reflection, perception-checking, and empathy. These three skills can help you identify errors in your assessment of the event or person and plan a competent response. The Jefferson strategy is especially easy to use when you’re communicating by e-mail or text-messaging, two media that naturally allow for a delay between receiving a message and responding.