5.1.1 Receiving

Printed Page 147

Receiving

While walking to class, you unexpectedly run into a good friend and stop to chat with her. As she talks, you listen to her words as well as observe her behavior. But how does this process happen? As you observe your friend, light reflects off her skin, clothes, and hair and travels through the lens of your eye to your retina, which contains optic nerves. These nerves become stimulated, sending information to your brain, which translates the information into visual images such as your friend smiling or shaking her head, an effect called seeing. At the same time, sound waves generated by her voice enter your inner ear, causing your eardrum to vibrate. These vibrations travel along acoustic nerves to your brain, which interprets them as your friend’s words and voice tone, an effect known as hearing.

Together, seeing and hearing constitute receiving, the first step in the listening process. Receiving is critical to listening—you can’t listen if you don’t “see” or hear the other person. Unfortunately, our ability to receive is often hampered by noise pollution, sound in the surrounding environment that obscures or distracts our attention from auditory input. Sources of noise pollution include crowds, road and air traffic, construction equipment, and music.

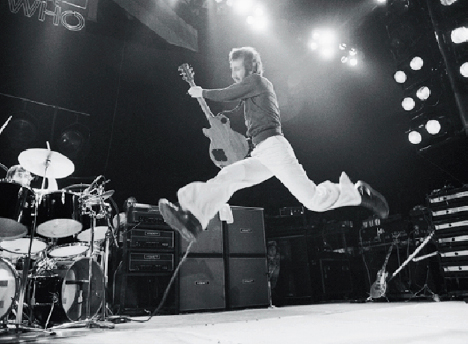

Although noise pollution is inescapable, especially in large cities, some people intentionally expose themselves to intense levels of noise pollution. This can result in hearing impairment, the restricted ability to receive sound input across the humanly audible frequency range. For example, research suggests that more than 40 percent of college students have measurable hearing impairment due to loud music in bars, home stereos, headphones, and concerts, but only 8 percent believe that it is a “big problem” compared with other health issues (Chung, Des Roches, Meunier, & Eavey, 2005). One study of rock and jazz musicians found that 75 percent suffered substantial hearing loss from exposure to chronic noise pollution (Kaharit, Zachau, Eklof, Sandsjo, & Moller, 2003).

You can enhance your ability to receive—and improve your listening as a result—by becoming aware of noise pollution and adjusting your interactions accordingly. Practice monitoring the noise level in your environment during your interpersonal encounters, and notice how it impedes your listening. When possible, avoid interactions in loud and noisy environments, or move to quieter locations when you wish to exchange important information with others. If you enjoy loud music or live concerts, always use ear protection to ensure your auditory safety. As a lifelong musician, I myself never practice, play a gig, or attend a concert without earplugs.