5.1.5 Responding

Printed Page 153

Responding

You’re spending the afternoon at your apartment discussing your wedding plans with two friends, John and Sarah. You want them to help you with ideas for your rehearsal dinner, ceremony, and reception. As you talk, John looks directly at you, smiles, nods his head, and leans forward. He also asks questions and makes comments periodically during the discussion. Sarah, in contrast, seems completely uninterested. She alternates between looking at the people strolling by your living-room window and texting on her phone. She also sits with her body half-turned away from you and leans back in her chair. You become frustrated because it’s obvious that John is listening closely and Sarah isn’t listening at all.

What leads you to conclude that John is listening and Sarah isn’t? It’s the way your friends are responding—communicating their attention and understanding to you. Responding is the fourth stage of the listening process. When you actively listen, you do more than simply attend and understand. You also convey your attention and understanding to others by clearly and constructively responding through positive feedback, paraphrasing, and clarifying (McNaughton et al., 2007).

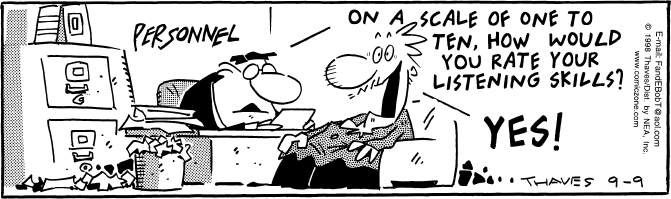

FRANK & ERNEST © 1998 Thaves. Reprinted by permission of UNIVERSAL UCLICK for UFS. All right reserved.

Feedback Critical to active listening is using verbal and nonverbal behaviors known as feedback to communicate attention and understanding while others are talking. Scholars distinguish between two kinds of feedback, positive and negative (Wolvin & Coakley, 1996). When you use positive feedback, like John in our earlier example, you look directly at the person speaking, smile, position your body so that you’re facing him or her, and lean forward. You may also offer back-channel cues, verbal and nonverbal behaviors such as nodding and making comments—like “Uh-huh,” “Yes,” and “That makes sense”—that signal you’ve paid attention to and understood specific comments (Duncan & Fiske, 1977). All of these behaviors combine to show speakers that you’re actively listening. In contrast, people who use negative feedback, like Sarah in our example, send a very different message to speakers: “I’m not interested in paying attention to you or understanding what you’re saying.” Behaviors that convey negative feedback include avoiding eye contact, turning your body away, looking bored or distracted, and not using back-channel cues.

Question

The type of feedback we provide while we’re listening has a dramatic effect on speakers (Wolvin & Coakley, 1996). Receiving positive feedback from listeners can enhance a speaker’s confidence and generate positive emotions. Negative feedback can cause speakers to hesitate, make speech errors, or stop altogether to see what’s wrong and why we’re not listening.

To effectively display positive feedback during interpersonal encounters, try four simple suggestions (Barker, 1971; Daly, 1975). First, make your feedback obvious. As communication scholar John Daly notes, no matter how actively you listen, unless others perceive your feedback, they won’t view you as actively listening. Second, make your feedback appropriate. Different situations, speakers, and messages require more or less intensity of positive feedback. Third, make your feedback clear by avoiding behaviors that might be mistaken as negative feedback. For example, something as simple as innocently stealing a glance at your phone to see what time it is might unintentionally suggest that you’re bored or wish the person would stop speaking. Finally, always provide feedback quickly in response to what the speaker has just said.

Paraphrasing and Clarifying Active listeners also communicate attention and understanding through saying things after their conversational partners have finished their turns—things that make it clear they were listening. One way to do this is by paraphrasing, summarizing others’ comments after they have finished (“My read on your message is that . . .” or “You seem to be saying that . . .”). This practice can help you check the accuracy of your understanding during both face-to-face and online encounters. Paraphrasing should be used judiciously, however. Some conversational partners may find paraphrasing annoying if you use it a lot or they view it as contrived. Paraphrasing can also lead to conversational lapses, silences of three seconds or longer that participants perceive as awkward (McLaughlin & Cody, 1982).

Paraphrasing can cause lapses because when you paraphrase, you do nothing to usefully advance the conversational topic forward in new and interesting ways (Heritage & Watson, 1979). Instead, you simply rehash what has already been said. Consequently, the only relevant response your conversational partner can provide is a simple acknowledgment, such as “Yeah” or “Uh-huh.” In such cases, a lapse is likely to ensue immediately after, unless one of you has a new topic ready to introduce to advance the conversation. This is an important practical concern for anyone interested in being perceived as interpersonally competent because the more lapses that occur, the more likely your conversational partner is to perceive you as incompetent (McLaughlin & Cody, 1982). To avoid this perception, always couple your paraphrasing with additional comments or questions that usefully build on the previous topic or take the conversation in new directions.

Of course, on some occasions, we simply don’t understand what others have said. In such instances, it’s perfectly appropriate to respond by seeking clarification rather than paraphrasing, saying, “I’m sorry, but could you explain that again? I want to make sure I understood you correctly.” This technique not only helps you clarify the meaning of what you’re hearing, it also enables you to communicate your desire to understand the other person.

Responding Online

- Responding effectively during online encounters

-

Identify an online interaction that’s important.

Identify an online interaction that’s important. -

During the exchange, provide your conversational partner with immediate, positive feedback to his or her messages, sending short responses like “I agree!” and attaching positive emoticons.

During the exchange, provide your conversational partner with immediate, positive feedback to his or her messages, sending short responses like “I agree!” and attaching positive emoticons. -

Check your understanding by paraphrasing your partner’s longer messages (“My read on your last message is . . .”).

Check your understanding by paraphrasing your partner’s longer messages (“My read on your last message is . . .”). -

Seek clarification regarding messages you don’t understand (“I’m having trouble understanding— would you mind explaining that a bit more?”).

Seek clarification regarding messages you don’t understand (“I’m having trouble understanding— would you mind explaining that a bit more?”).