8.4.1 Approaches to Handling Conflict

Printed Page 255

Approaches to Handling Conflict

People generally handle conflict in one of five ways: avoidance, accommodation, competition, reactivity, or collaboration (Lulofs & Cahn, 2000; Zacchilli et al., 2009). Before reading about each approach, take the Self-Quiz on page 256 to find out how you typically approach conflict.

Avoidance One way to handle conflict is avoidance: ignoring the conflict, pretending it isn’t really happening, or communicating indirectly about the situation. One common form of avoidance is skirting, in which a person avoids a conflict by changing the topic or joking about it. You think your lover is having an affair and raise the issue, but he or she just laughs and says (in a Southern accent), “Don’t you know we’ll always be together, like Noah and Allie from The Notebook?” Another form of avoidance is sniping —communicating in a negative fashion and then abandoning the encounter by physically leaving the scene or refusing to interact further. You’re fighting with your brother through Skype, when he pops off a nasty comment (“I see you’re still a spoiled brat!”) and signs off before you have a chance to reply.

Avoidance is the most frequently used approach to handling conflict (Sillars, 1980). People opt for avoidance because it seems easier, less emotionally draining, and lower risk than direct confrontation (Afifi & Olson, 2005). But avoidance poses substantial risks (Afifi et al., 2009). One of the biggest is cumulative annoyance, in which repressed irritation grows as the mental list of grievances we have against our partners builds (Peterson, 2002). Eventually, cumulative annoyance overwhelms our capacity to suppress it and we suddenly explode in anger. For example, you constantly remind your teenage son about his homework, chores, personal hygiene, and room cleanliness. This bothers you immensely because you feel these matters are his responsibility, but you swallow your anger because you don’t want to make a fuss or be seen by him as “nagging.” One evening, after reminding him twice to hang up his expensive new leather jacket, you walk into his bedroom to find the coat crumpled in a ball on the floor. You go on a tirade, listing all of the things he has done to upset you in the past month.

Question

A second risk posed by avoidance is pseudo-conflict , the perception that a conflict exists when in fact it doesn’t. For example, you mistakenly think your romantic partner is about to break up with you because you see tagged photos of him or her arm in arm with someone else on Facebook. So you decide to preemptively end your relationship even though your partner actually has no desire to leave you (the photos were of your partner and a cousin).

Despite the risks, avoidance can be a wise choice for managing conflict in situations where emotions run high (Berscheid, 2002). If everyone involved is angry, and yet you choose to continue the interaction, you run the risk of saying things that will damage your relationship. It may be better to avoid through leaving, hanging up, or not responding to texts or messages until tempers have cooled.

Accommodation Through accommodation , one person abandons his or her own goals and acquiesces to the desires of the other person. For example, your supervisor at work asks you to stay an extra hour tonight because a coworker is showing up late. Although you had plans for the evening, you cancel them and act as if it’s not a problem.

If you’re like most people, you probably accommodate people who have more power than you. Why? If you don’t, they might use their power to control or punish you. This suggests an important lesson regarding the relationship between power and conflict: people who are more powerful than you probably won’t accommodate your goals during conflicts.

Another factor that influences people’s decision to accommodate is love. Accommodation reflects a high concern for others and a low concern for self; you want to please those you love (Frisby & Westerman, 2010). Hence, accommodation is likely to occur in healthy, satisfied close relationships where selflessness is characteristic (Hendrick & Hendrick, 1992). For example, your romantic partner is accepted into a summer study-abroad program in Europe. Even though you had planned on spending the summer together, you encourage him or her to accept the offer.

Accommodation

Watch this clip to answer the questions below.

Question

Want to see more? Check out the Related Content section for additional clips on avoidance, sniping, competition, and collaboration.

Competition Think back to the airline conflict. Each of the men involved aggressively challenged the other and expressed little concern for the other’s perspective or goals. This approach is known as competition : an open and clear discussion of the goal clash that exists and the pursuit of one’s own goals without regard for others’ goals (Sillars, 1980).

The choice to use competition is motivated in part by negative thoughts and beliefs, including a desire to control, a willingness to hurt others in order to gain, and a lack of respect for others (Bevan, Finan, & Kaminsky, 2008; Zacchilli et al., 2009). Consequently, you’ll be less likely to opt for competition when you are in a conflict with someone whose needs you are interested in and whom you admire. Conversely, if people routinely approach conflict by making demands to the exclusion of your desires, they likely do not respect you (Hendrick & Hendrick, 2006).

At a minimum, competitive approaches can trigger defensive communication (described in Chapter 6)—someone refusing to consider your goals or dismissing them as unimportant, acting superior to you, or attempting to squelch your disagreement by wielding power over you (Waldron, Turner, Alexander, & Barton, 1993). But the primary risk of choosing a competitive approach is escalation , a dramatic rise in emotional intensity and increasingly negative and aggressive communication—just like in the airline dispute. If people in conflict both choose competition, and neither is willing to back down, escalation is guaranteed. Even initially trivial conflicts can quickly explode into intense exchanges.

Reactivity A fourth way people handle conflict is by not pursuing any conflict-related goals at all; instead, they communicate in an emotionally explosive and negative fashion. This is known as reactivity , and is characterized by accusations of mistrust, yelling, crying, and becoming verbally or physically abusive. Reactivity is decidedly nonstrategic. Instead of avoiding, accommodating, or competing, people simply “flip out.” For example, one of my college dating partners was intensely reactive. When I noted that we weren’t getting along, and suggested taking a break, she screamed “I knew it! You’ve been cheating on me!” and hurled a vase of roses I had given her at my head. Thankfully I ducked out of the way, but it took the campus police to calm her down. Her behavior had nothing to do with “managing our conflict.” She simply reacted.

Similar to competition, reactivity is strongly related to a lack of respect (Bevan et al., 2008; Zacchilli et al., 2009). People prone to reactivity have little interest in others as individuals, and do not recognize others’ desires as relevant (Zacchilli et al., 2009).

Question

Collaboration The most constructive approach to managing conflict is collaboration: treating conflict as a mutual problem-solving challenge rather than something that must be avoided, accommodated, competed over, or reacted to. Often the result of using a collaborative approach is compromise, where everyone involved modifies their individual goals to come up with a solution to the conflict. (We’ll discuss compromise more on page 265.) You’re most likely to use collaboration when you respect the other person and are concerned about his or her desires as well as your own (Keck & Samp, 2007; Zacchilli et al., 2009). People who regularly use collaboration feel more trust, commitment, and overall satisfaction with their relationships than those who don’t (Smith, Heaven, & Ciarrochi, 2008). Whenever possible, opt for collaboration.

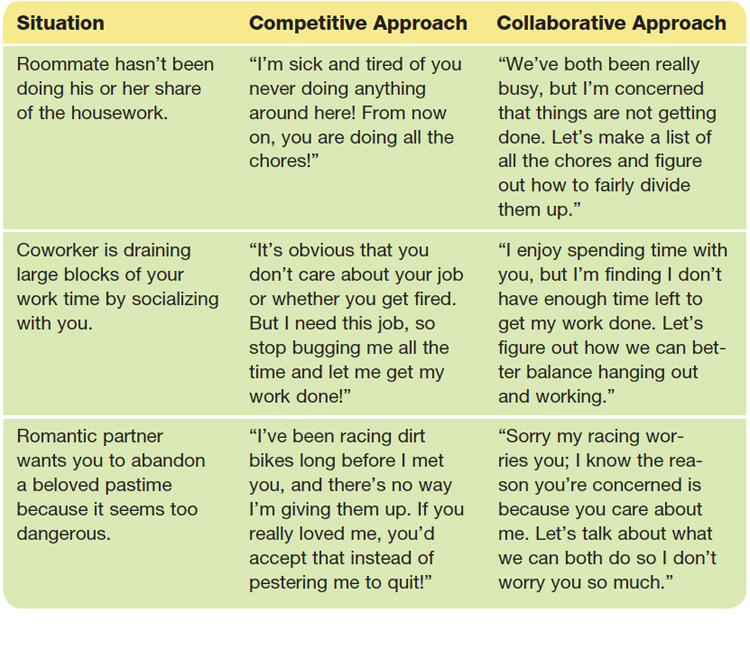

Table 8.2 Competitive versus Collaborative Conflict Approaches

To use a collaborative approach, try these suggestions from Wilmot and Hocker (2010). First, attack problems not people. Talk about the conflict as something separate from the people involved, saying, for instance, “This issue has really come between us.” This frames the conflict as the source of trouble and unites the people trying to handle it. At the same time, avoid personal attacks while being courteous and respectful, regardless of how angry you may be. This is perhaps the hardest part of collaboration, because you likely will be angry during conflicts (Berscheid, 2002). Just don’t let your anger cause you to say and do things you shouldn’t. If someone attacks you and not the problem, don’t get sucked into trading insults. Simply say “I can see you’re very upset; let’s talk about this when we’ve both had a chance to cool off,” and end the encounter before things escalate further.

Second, focus on common interests and long-term goals. Keep the emphasis on the desires you share in common, not the issue that’s driving you apart. Use “we” language (see Chapter 6) to bolster this impression: “I know we both want what’s best for the company.” Arguing over positions (“I want this!” versus “I want that!”) endangers relationships because the conflict quickly becomes a destructive contest of wills.

Third, create options before arriving at decisions. Be willing to negotiate a solution, rather than insist on one. To do this, start by asking questions that will elicit options: “How do you think we can best resolve this?” or “What ideas for solutions do you have?” Then propose ideas of your own. Be flexible. Most collaborative solutions involve some form of compromise, so be willing to adapt your original desires, even if it means not getting everything you want. Then combine the best parts of the various suggestions to come up with an agreeable solution. Don’t get bogged down searching for a “perfect” solution—it may not exist.

Finally, critically evaluate your solution. Ask for an assessment: “Is this equally fair for both of us?” The critical issue is livability: Can everyone live with the resolution in the long run? Or, is it so unfair or short of original desires that resentments are likely to emerge? If anyone can answer “yes” to the latter question, go back to creating options (Step 3) until you find a solution that is satisfactory to everyone.

Collaboration

- Using collaboration to manage a conflict

-

During your next significant conflict, openly discuss the situation, emphasizing that it’s an understandable clash between goals rather than people.

During your next significant conflict, openly discuss the situation, emphasizing that it’s an understandable clash between goals rather than people. -

Highlight common interests and long-term goals.

Highlight common interests and long-term goals. -

Create several solutions for resolving the conflict that are satisfactory to both of you.

Create several solutions for resolving the conflict that are satisfactory to both of you. -

Combine the best elements of these ideas into a single, workable solution.

Combine the best elements of these ideas into a single, workable solution. -

Evaluate the solution you’ve collaboratively created, ensuring that it’s fair and ethical.

Evaluate the solution you’ve collaboratively created, ensuring that it’s fair and ethical.