8.3.3 Power and Culture

Printed Page 252

Power and Culture

Views of power differ substantially across cultures. Power derives from the perception of power currencies, so people are granted power not only according to which power currencies they possess, but also according to the degree to which those power currencies are valued in a given culture. In Asian and Latino cultures, high value is placed on resource currency; consequently, people without wealth, property, or other such material resources are likely to grant power to those who possess them (Gudykunst & Kim, 2003). In contrast, in northern European countries, Canada, and the United States, people with wealth may be admired or even envied, but they are not granted unusual power. If your rich neighbor builds a huge mansion, you might be impressed. But if her new fence crosses onto your property, you’ll confront her about it (“Sorry to bother you, but your new fence is one foot over the property line”). Members of other cultures would be less likely to say anything, given her wealth and corresponding power.

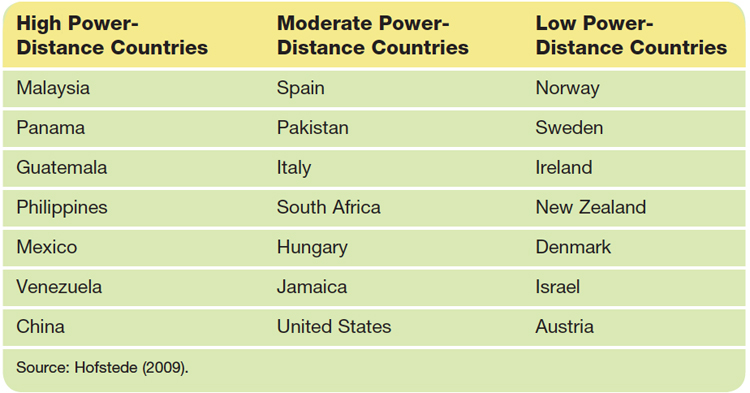

Cultures also differ widely in the degree to which people view the unequal distribution of power as acceptable, known as power-distance (Hofstede, 1991, 2001). In high power-distance cultures, it’s considered normal and even desirable for people of different social and professional status to be widely separated in terms of their power. Within such cultures, people give privileged treatment and extreme respect to those in high-status positions (Ting-Toomey, 1999). People of lesser status are expected to behave humbly, especially when they’re around people of higher status, while high-status people are expected to act superior. In low power-distance cultures, people in high-status positions strive to minimize the differences between themselves and lower-status persons, often interacting with lower-status persons in an informal and equal fashion (see Table 8.1).

Power-distance influences how people deal with conflict. In low power-distance cultures, people who possess few power currencies may still choose to engage in conflict with high-power people. Employees may question management decisions, or people may attend a town meeting and argue with the mayor. These behaviors are much less likely to occur in high power-distance cultures (Bochner & Hesketh, 1994).

Power-distance also plays a role in shaping close relationship communication, especially in families. In traditional Mexican culture, for instance, the value of respeto emphasizes power-distance between those who are younger and their elders (Delgado-Gaitan, 1993). As part of respeto, children are expected to defer to elders’ authority and to avoid openly disagreeing with them. In contrast, many Euro-Americans believe that once children reach the age of adulthood, power in family relationships should be balanced—children and their elders treating one another in a symmetrical fashion as friends (Kagawa & McCornack, 2004).

Table 8.1 Power-Distance across Countries