9.2.2 Different Types of Romantic Love

Printed Page 282

Different Types of Romantic Love

Though most people recognize that loving differs from liking, many also believe that to be in love, one must feel constant and consuming sexual attraction toward a partner. In fact, many different types of romantic love exist, covering a broad range of emotions and relationship forms. At one end of the spectrum is passionate love, a state of intense emotional and physical longing for union with another (Hendrick & Hendrick, 1992). For example, in Helen Simonson’s best-selling novel Major Pettigrew’s Last Stand (2011), Ernest and Jasmina are lovers facing bitter opposition from friends and family because of their interethnic romance (he is English, she Pakistani). After sharing the night together at a secluded lodge, they awake and celebrate their passion.3

In the early morning he stood by the empty lake and watched a lone bird, falcon or eagle, gliding high on the faintest of thermals. He raised his arms to the air, stretching with his fingertips, and wondered whether the bird’s heart was as full as his own. As he gazed, the French door was pushed open and she came out, carrying two mugs of tea, which steamed in the air. “You should have woken me,” she said, “I hope you weren’t fleeing the scene?” “I needed to do a little capering about,” he said. “Some beating of the chest and cheering—manly stuff.” “Oh, do show me,” she said, laughing, while he executed a few half-remembered dance steps, and kicked a large stone into the lake. “Do I get a turn?” she asked. She handed him a mug for each hand and then spun herself in wild pirouettes to the shore where she stomped her feet in the freezing waters. Then she came running back and kissed him while he spread his arms wide and tried to keep his balance. “Careful,” he said, feeling a splash of scalding tea on his wrist. “Passion is all very well, but it wouldn’t do to spill the tea.”

If you’ve been passionately in love before, these feelings likely are familiar: the desire to stretch for the sky, dance, laugh, and splash about, coupled with a strong desire to touch, hold, and kiss your partner. Studies of passionate love support the universality of these sentiments, and suggest that five things are true about the experience and expression of passion. First, people in the throes of passionate love often view their loved ones and relationships in an excessively idealistic light. For instance, many partners in passionate love relationships talk about how “perfect” they are for each other and how their relationship is the “best ever.”

Second, people from all cultures feel passionate love. Studies comparing members of individualistic versus collectivistic cultures have found no differences in the amount of passionate love experienced (Hatfield & Rapson, 1987). Although certain ethnicities, especially Latinos, often are stereotyped as more “passionate,” studies comparing Latino and non-Latino experiences of romantic love suggest no differences in intensity (Cerpas, 2002).

Third, no gender or age differences exist in people’s experience of passionate love. Men and women report experiencing this type of love with equal frequency and intensity, and studies using a “Juvenile Love Scale” (which excludes references to sexual feelings) have found that children as young as age 4 report passionate love toward others (Hatfield & Rapson, 1987). The latter finding is important to consider when talking with children about their romantic feelings. Although they lack the emotional maturity to fully understand the consequences of their relationship decisions, their feelings toward romantic interests are every bit as intense and turbulent as our adult emotions. So if your 6- or 7-year-old child or sibling reveals a crush on a schoolmate, treat the disclosure with respect and empathy, rather than teasing him or her.

Fourth, for adults, passionate love is integrally linked with sexuality and sexual desire (Berscheid & Regan, 2005). In one study, undergraduates were asked whether they thought there was a difference between “being in love” and “loving” another person (Ridge & Berscheid, 1989). Eighty-seven percent of respondents said that there was a difference and that sexual attraction was the critical distinguishing feature of being in love.

Finally, passionate love is negatively related to relationship duration. Like it or not, the longer you’re with a romantic partner, the less intense your passionate love will feel (Berscheid, 2002).

Question

Although the “fire” of passionate love dominates media depictions of romance, not all people view being in love this way. At the other end of the romantic spectrum is companionate love: an intense form of liking defined by emotional investment and deeply intertwined lives (Berscheid & Walster, 1978). Many long-term romantic relationships evolve into companionate love. As Clyde and Susan Hendrick (1992) explain, “Sexual attraction, intense communication, and emotional turbulence early in a relationship give way to quiet intimacy, predictability, and shared attitudes, values, and life experiences later in the relationship” (p. 48).

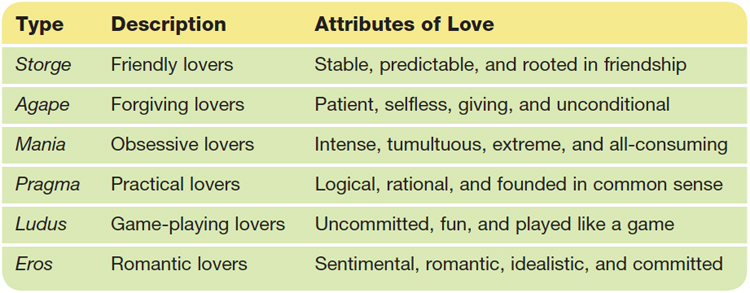

Between the poles of passionate and companionate love lies a range of other types of romantic love. Sociologist John Alan Lee (1973) suggested six different forms that range from friendly to obsessive and gave them each a traditional Greek name: storge, agape, mania, pragma, ludus, and eros (see Table 9.1 for an explanation of each). As Lee noted, there is no “right” type of romantic love—different forms appeal to different people.

Despite similarities between men and women in their experiences of passionate love, substantial gender differences exist related to one of Lee’s love types—pragma, or “practical love.” Across numerous studies, women score higher than men on pragma (Hendrick & Hendrick, 1988, 1992), refuting the common stereotype that women are “starry-eyed” and “sentimental” about romantic love (Hill, Rubin, & Peplau, 1976). What’s more, although men are often stereotyped as being “cool” and “logical” about love (Hill et al., 1976), they are much more likely than women to perceive their romantic partners as “perfect” and believe that “love at first sight is possible,” that “true love can overcome any obstacles,” and that “there’s only one true love for each person” (Sprecher & Metts, 1999).

Table 9.1 Romantic Love Types