Technology And Family Maintenance

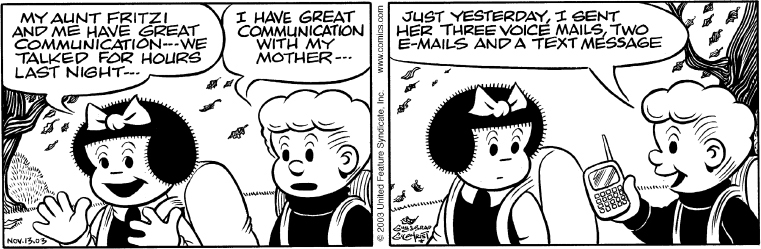

TECHNOLOGY AND FAMILY MAINTENANCE

My parents live two thousand miles away from me, in an isolated valley in southern Oregon. But we “talk” several times each week by e-mail—exchanging cartoons, photos, and articles of interest. My nephew John, a student at the University of Washington, chats with me regularly via Facebook. And my oldest son, Kyle, while doing his homework upstairs, routinely sends me music and movie clips—even as I sit in our living room below, working.

Technology and Family Maintenance

Ways to communicate positivity and assurances to family members

-

Send an e-mail to a family member with whom you’ve been out of touch, letting him or her know you care.

-

Offer congratulations via text or e-mail to a family member who has recently achieved an important goal.

-

Post a message on the Facebook page of a family member with whom you’ve had a disagreement, saying that you value his or her opinions and beliefs.

-

Send an e-card to a long-distance family member, sharing a message of affection.

-

Post a supportive response to a family member who has expressed concerns via Twitter or Facebook.

Although some lament that technology has replaced face-to-face interaction and reduced family intimacy (“Families are always on the computer and never talk any more!”), families typically use online and face-to-face communication in a complementary, rather than substitutive, fashion. Families who communicate frequently via e-mail, Facebook, and IM also communicate frequently face-to-face or on the phone. They typically choose synchronous modes of communication (face-to-face, phone) for personal or urgent matters, and asynchronous modes (e-mail, text, Facebook) for less important issues (Tillema, Dijst, & Schwanen, 2010). What’s more, technology, especially the use of cell phones, allows families to connect, share, and coordinate their lives to a degree never before possible, resulting in boosted intimacy and satisfaction (Kennedy, Smith, Wells, & Wellman, 2008). Similarly, families whose members are geographically separated but who use online communication to stay in touch report higher satisfaction, stronger intimacy, more social support, and reduced awareness of the physical separation, compared to families who don’t (McGlynn, 2007).

Despite being comparatively “old school,” e-mail is the dominant electronic way families communicate. Interpersonal scholar Amy Janan Johnson and her colleagues found that more than half of college students reported interacting with family members via e-mail in the preceding week and that the primary purpose of these e-mails was relationship maintenance (Johnson, Haigh, Becker, Craig, & Wigley, 2008). Students used e-mail to maintain positivity (“Have a great day!”), provide assurances (“I love you and miss you!”), and self-disclose (“I’m feeling a bit scared about my stats exam tomorrow”).

Of course, the biggest advantage of online communication is that, unlike face-to-face and phone, it lets you get in touch with family members at any time (Oravec, 2000). For example, my folks and I live in different time zones, making it difficult to find times we can talk. But we still share day-to-day events and interests via e-mail and text messages. Rarely a day goes by when I don’t receive a message from my mom detailing their dog Teddy’s latest feat of canine intelligence, or from my dad about his progress on his MG “project car.” Such messages make us feel close, even though we’re thousands of miles apart.