Disclosing Your Self to Others

DISCLOSING YOUR SELF TO OTHERS

In Eowyn Ivey’s novel, The Snow Child (2012), Mabel and Jack are a couple mired in grief following the death of their only child. Early in the story, Mabel’s depression leads her to attempt suicide by walking across a newly frozen river, presuming she’ll break through the ice and drown. Instead, the ice holds, and she survives. Later, over dinner, she struggles to share her experience—and her despair—with Jack.

“I went to the river today,” she said. She waited for him to ask why she would do such a thing. Maybe then she could tell him. He gave no indication he had heard her. “It’s frozen all the way across to the cliffs,” she said in a near whisper. Her eyes down, her breath shallow, she waited, but there was only Jack’s chewing. Mabel looked up and saw his windburned hands and the crow’s feet that spread at the corners of his downturned eyes. She couldn’t remember the last time she had touched that skin, and the thought ached like loneliness in her chest. Then she spotted a few strands of silver in his reddish-brown beard. When had they appeared? So he, too, was graying. Each of them fading away without the other’s notice. “That ice isn’t solid yet,” Jack said from across the table. “Best to stay off it.” Mabel swallowed, cleared her throat. “Yes. Of course.”5

We all can think of situations in which we’ve struggled with whether to share deeply personal thoughts, feelings, or experiences with others. Revealing private information about ourselves is known as self-disclosure (Wheeless, 1978), and it plays a critical role in interpersonal communication and relationship development. According to the interpersonal process model of intimacy, the closeness we feel toward others in our relationships is created through two things: self-disclosure and responsiveness of listeners to disclosure (Reis & Patrick, 1996). Relationships are intimate when both partners share private information with each other and each partner responds to the other’s disclosures with understanding, caring, and support (Reis & Shaver, 1988).

Four practical implications flow from this model. First, like Mabel and Jack in The Snow Child, you can’t have intimacy in a relationship without disclosure and supportiveness. If you, like Mabel, view a friend, family member, or lover as being nonsupportive, you likely won’t disclose private thoughts and feelings to that person, and your relationship will be less intimate as a result. Second, if listeners are nonsupportive after a disclosure, the impact on intimacy can be devastating. Think about an instance in which you shared something personal with a friend, but he or she responded by ridiculing or judging you. How did this reaction make you feel? Chances are, it substantially widened the emotional distance between the two of you. Third, just because you share your thoughts and feelings with someone doesn’t mean that you have an intimate relationship. For example, if you regularly chat with a classmate and tell her all of your secrets, but she never does the same in return, your relationship isn’t intimate, it’s one sided. In a similar fashion, tweeting or posting personal thoughts and feelings and having people read them doesn’t create intimate relationships. Intimacy only exists when both people are sharing with and supporting each other.

And finally, not all disclosures boost intimacy. Research suggests that one of the most damaging events that can happen in interpersonal relationships is a partner’s sharing information that the other person finds inappropriate and perplexing (Planalp & Honeycutt, 1985). This is especially true in relationships in which the partners are already struggling with a challenging problem or experiencing a painful transition. For example, during divorce proceedings, parents commonly disclose negative and demeaning information about each other to their children. The parents may see this sharing as stress-relieving or “cathartic” (Afifi, McManus, Hutchinson, & Baker, 2007). But these disclosures only intensify the children’s mental and physical distress and make them feel caught between the two parents (Koerner, Wallace, Lehman, & Raymond, 2002).

Differences in Disclosure Researchers have conducted thousands of self-disclosure studies over the past 40 years (Tardy & Dindia, 1997). These studies suggest five important facts regarding how people self-disclose.

First, in any culture, people vary widely in the degree to which they self-disclose. Some people are naturally transparent whereas others are more opaque (Jourard, 1964). Trying to force someone who has a different idea of self-disclosure than yours to open up or be more discreet not only is presumptuous but can damage the relationship (Luft, 1970).

Second, people across cultures differ in their self-disclosure. For instance, people of Asian descent tend to disclose less than people of European ancestry. Japanese disclose substantially less than Americans in both friendships and romantic relationships, and they view self-disclosure as a less important aspect of intimacy development than do Americans (Barnlund, 1975). In general, Euro-Americans tend to disclose more frequently than just about any other cultural group, including Asians, Hispanics, and African Americans (Klopf, 2001).

Third, people disclose differently online than they do face-to-face, and such differences depend on the intimacy of the relationship. When people are first getting to know each other, they typically disclose more quickly, broadly, and deeply when interacting online than face-to-face. One reason for this is that online encounters lack nonverbal cues (tone of voice, facial expressions), so the consequences of such disclosure seem less noticeable, and words take on more importance and intensity than those exchanged during face-to-face interactions (Joinson, 2001). The consequence is that we often overestimate the intimacy of online interactions and relationships with acquaintances or strangers. However, as relationships mature and intimacy increases, the relationship between communication medium and disclosure reverses. Individuals in close relationships typically use online communication for more trivial exchanges (such as coordinating schedules, updating each other on mundane daily events, and so forth), and reserve their deeper, more meaningful discussions for when they are face-to-face (Ruppel, 2014).

To help ensure competent online disclosure, scholar Malcolm Parks offers the following advice: Be wary of the emotionally seductive qualities of online interaction.6 Disclose information slowly and with caution. Remember that online communication is both public and permanent; hence, secrets that you tweet, post, text, or e-mail are no longer secrets. Few experiences in the interpersonal realm are more uncomfortable than “post-cyber-disclosure panic”—that awful moment when you wonder who else might be reading the innermost thoughts you just revealed in an e-mail or a text message to a friend (Barnes, 2001).

Fourth, self-disclosure appears to promote mental health and relieve stress (Tardy, 2000). When the information is troubling, keeping it inside can escalate your stress levels substantially, resulting in problematic mental and physical symptoms and ailments (Pennebaker, 1997; Kelly & McKillop, 1996). Of course, the flip side of disclosing troubling secrets to others is that people might react negatively and you might be more vulnerable.

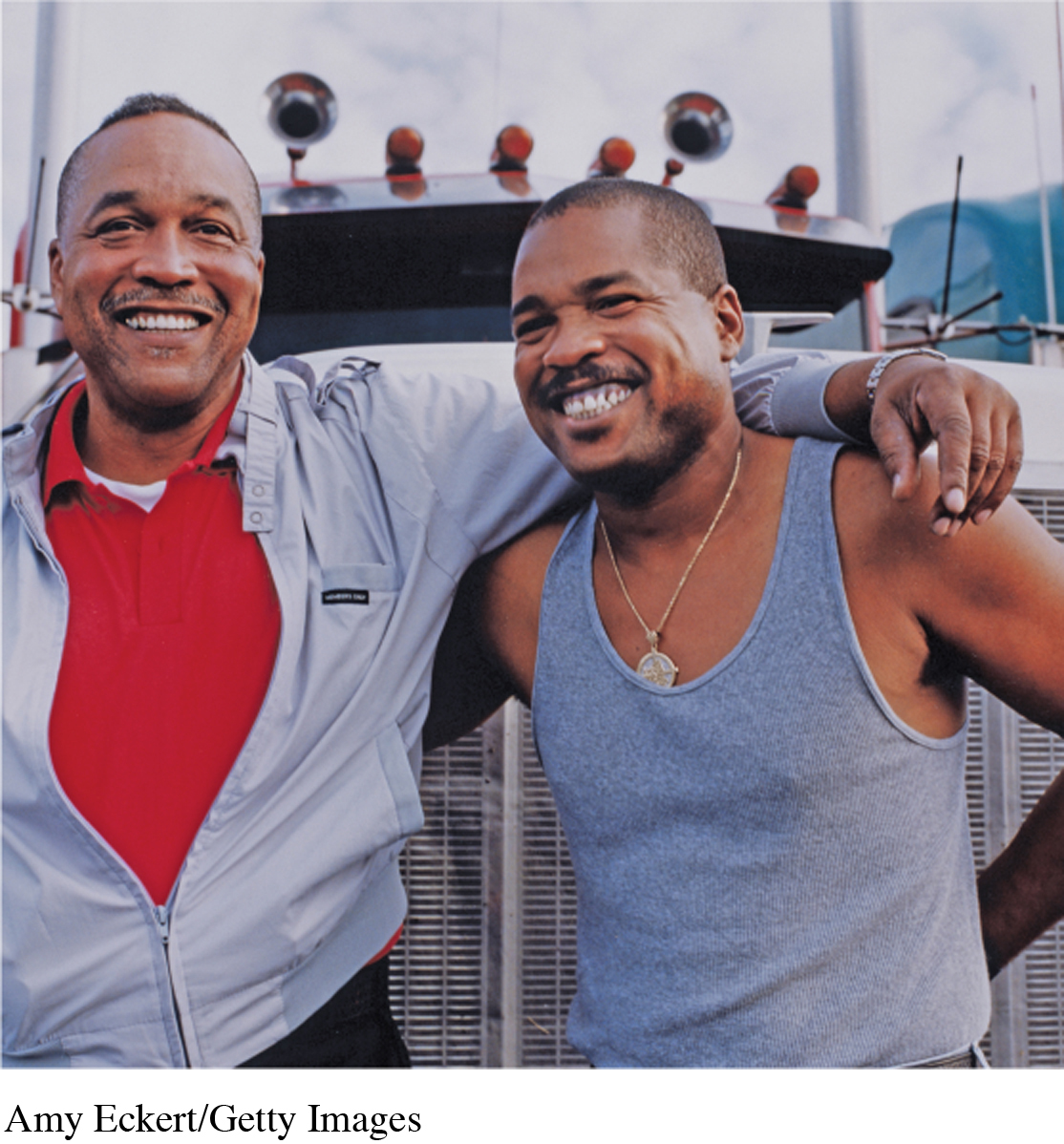

Finally, and importantly, little evidence exists that supports the stereotype that men can’t disclose their feelings in relationships. In close same-sex friendships, for example, both men and women disclose deeply and broadly (Shelton et al., 2010). And in cross-sex romantic involvements, men often disclose at levels equal to or greater than their female partners (Canary et al., 1997). At the same time, however, both men and women feel more comfortable disclosing to female than to male recipients (Dindia & Allen, 1992). Teenagers are more likely to disclose to mothers and best female friends than to fathers and best male friends—suggesting that adolescents may perceive females as more empathic and understanding than males (Garcia & Geisler, 1988).

Competently Disclosing Your Self Based on all we know about self-disclosure, how can you improve your disclosure skills? Consider these recommendations for competent self-disclosure:

Follow the advice of Apollo: know your self. Before disclosing, make sure that the aspects of your self you reveal to others are aspects that you want to reveal and that you feel certain about. This is especially important when disclosing intimate feelings, such as romantic interest. When you disclose feelings about others directly to them, you affect their lives and relationship decisions. Consequently, you’re ethically obligated to be certain about the truth of your own feelings before sharing them with others.

self-reflection

During your childhood, to which family member did you feel most comfortable disclosing? Why? Of your friends and family right now, do you disclose more to women or men, or is there no difference? What does this tell you about how gender has guided your disclosure decisions?

Know your audience. Whether it’s a Facebook timeline post or an intimate conversation with a friend, think carefully about how others will perceive your disclosure and how it will impact their thoughts and feelings about you. If you’re unsure of the appropriateness of a disclosure, don’t disclose. Instead of disclosing, talk more generally about the issue or topic first, gauging the person’s level of comfort with the conversation before revealing deeper information.

Don’t force others to self-disclose. We often presume it’s good for people to open up and share their secrets, particularly those that are troubling them. Although it’s perfectly appropriate to let someone know you’re available to listen, it’s unethical and destructive to force or cajole others into sharing information against their will. People have reasons for not wanting to tell you things—just as you have reasons for protecting your own privacy.

Don’t presume gender preferences. Don’t fall into the trap of thinking that because someone is a woman she will disclose freely, or that because he’s a man he’s incapable of discussing his feelings. Men and women are more similar than different when it comes to disclosure. At the same time, be mindful of the tendency to feel more comfortable disclosing to women. Don’t presume that because you’re talking with a woman it’s appropriate for you to freely disclose.

Be sensitive to cultural differences. When interacting with people from different backgrounds, disclose gradually. As with gender, don’t presume disclosure patterns based on ethnicity. Just because someone is Asian doesn’t mean he or she will be more reluctant to disclose than someone of European descent.

Go slowly. Share intermediate and central aspects of your self gradually and only after thorough discussion of peripheral information. Moving too quickly to discussion of your deepest fears, self-esteem concerns, and personal values not only increases your sense of vulnerability but may make others uncomfortable enough to avoid you.