Influences on Perception

A sense of directness dominates the perceptual process. Someone says something to us, and with lightning speed we focus our attention, organize information, and interpret its meaning. Although this process seems unmediated, powerful forces outside our conscious awareness shape our perception during every encounter, whether we’re communicating with colleagues, friends, family members, or lovers. Three of the most powerful influences on perception are culture, gender, and personality.

PERCEPTION AND CULTURE

Your cultural background influences your perception in at least two ways. Recall from Chapter 1 that culture is an established, coherent set of beliefs, attitudes, values, and practices shared by a large group of people. Whenever you interact with others, you interpret their communication in part by drawing on information from your schemata. But your schemata are filled with the beliefs, attitudes, and values you learned in your own culture (Gudykunst & Kim, 2003). Consequently, people raised in different cultures have different knowledge in their schemata, so they interpret one another’s communication in very different ways. Competent interpersonal communicators recognize this fact. When necessary and appropriate, they check the accuracy of their interpretation by asking questions such as, “I’m sorry, could you clarify what you just said?”

Second, culture affects whether you perceive others as similar to or different from yourself. When you grow up valuing certain cultural beliefs, attitudes, and values as your own, you naturally perceive those who share these with you as fundamentally similar to yourself—people you consider ingroupers (Allport, 1954). You may consider individuals from many different groups as your ingroupers as long as they share substantial points of cultural commonality with you, such as nationality, religious beliefs, ethnicity, socioeconomic class, or political views (Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher, & Wetherell, 1987). In contrast, you may perceive people who aren’t similar to yourself as outgroupers.

Perceiving others as ingroupers or outgroupers is one of the most important perceptual distinctions we make. We often feel passionately connected to our ingroups, especially when they are tied to central aspects of our self-concepts, such as sexual orientation, religious beliefs, or ethnic heritage. Consequently, we are more likely to give valued resources, such as money, time, and effort, to those who are perceived as ingroupers versus those who are outgroupers (Castelli, Tomelleri, & Zogmaister, 2008). Basically, we like, and want to support, people who are “like” us.

self-reflection

Consider people in your life whom you view as outgroupers. What points of difference lead you to see them that way? How does their outgrouper status shape your communication toward them? Is there anything you could learn about them that would lead you to judge them as ingroupers?

We also are more likely to form positive interpersonal impressions of people we perceive as ingroupers (Giannakakis & Fritsche, 2011). One study of 30 ethnic groups in East Africa found that members of each group perceived ingroupers’ communication as substantially more trustworthy, friendly, and honest than outgroupers’ communication (Brewer & Campbell, 1976). Similarly, when we learn that ingroupers possess negative traits, such as stubbornness or narrow-mindedness, we’re likely to dismiss the significance of this revelation, instead ascribing these traits to human nature (Koval, Laham, Haslam, Bastian, & Whelan, 2012). Discovering the same characteristics in outgroupers is likely to trigger a strong negative impression. And in cases in which people communicate in rude or inappropriate ways, you’re substantially more inclined to form negative, internal attributions if you perceive them as outgroupers (Brewer, 1999). So, for example, if a cashier chides you for attempting to break a large bill but he’s wearing a T-shirt emblazoned with a message advocating your beliefs and values, you’re likely to make an external attribution: “He’s just having a bad day.” The same communication coming from someone who is proudly displaying chestwide messages attacking your beliefs will likely provoke a negative, internal attribution: “What a jerk! He’s just like all those other people who believe that stuff!”

While categorizing people as ingroupers or outgroupers, it’s easy to make mistakes. For example, even if people dress differently than you do, they may hold beliefs, attitudes, and values similar to your own. If you assume they’re outgroupers based on surface-level differences, you may communicate with them in ways that prevent you from getting to know them better.

PERCEPTION AND GENDER

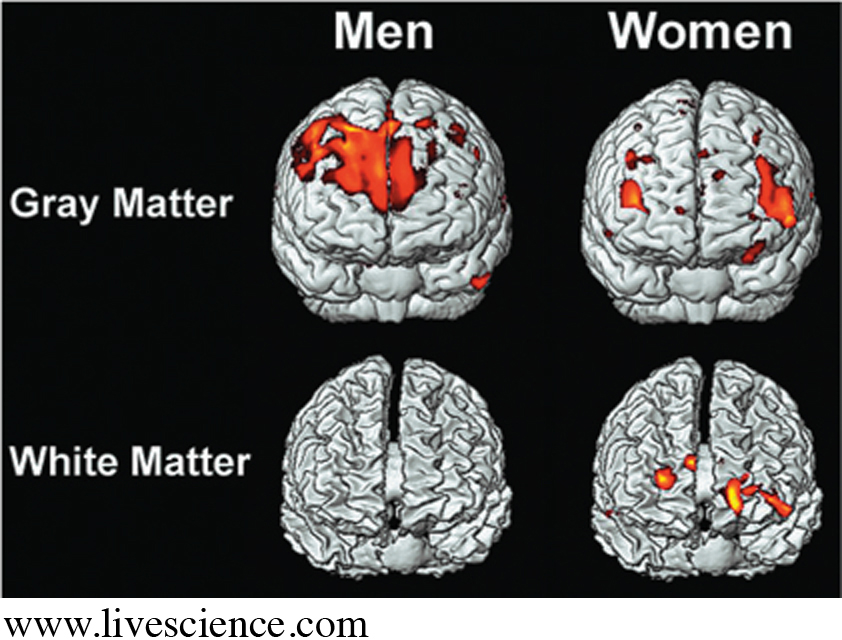

Get your family or friends talking about gender differences, and chances are you’ll hear most of them claim that men and women perceive interpersonal communication differently. They may insist that “men are cool and logical,” while “women see everything emotionally.” But the relationship between gender and perception is much more complex. For example, through magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron emission tomography (PET), we have learned that the structure of the brain’s cerebral cortex differs in men and women (Frederikse, Lu, Aylward, Barta, & Pearlson, 1999). Researchers maintain that this difference enables men to perceive time and speed more accurately than women do and to mentally rotate three-dimensional figures more easily. The difference in cerebral cortex structure allows women to understand and manipulate spatial relationships between objects more skillfully than men do and to more accurately identify others’ emotions. Women also have a greater ability to process information related to language simultaneously in both of the brain’s frontal lobes, resulting in higher scores on tests of language comprehension and vocabulary (Schlaepfer et al., 1995).

But whether variation in brain structure actually translates into differences in interpersonal communication is hotly debated among scholars. Linguist Deborah Tannen (1990) argues that men and women perceive and produce communication in vastly different ways. For example, Tannen suggests that when problems arise, men focus on solutions, and women offer emotional support. Consequently, women perceive men’s solutions as unsympathetic, and men perceive women’s needs for emotional support as unreasonable. In contrast, researchers from communication and psychology argue that men and women are actually more similar than different in how they interpersonally communicate (Hall, Carter, & Horgan, 2000). Researchers Dan Canary, Tara Emmers-Sommer, and Sandra Faulkner (1997) reviewed data from over 1,000 gender studies and found that if you consider all the factors that influence our communication and compare their impact, only about 1 percent of people’s communication behavior is caused by gender. They concluded that when it comes to interpersonal communication, “men and women respond in a similar manner 99% of the time” (p. 9).

Despite the debate over differences, we know one thing about gender and perception for certain: people are socialized to believe that men and women communicate differently. Within Western culture, people believe that women talk more about their feelings than men do, talk about “less important” issues than men do (women “gossip,” whereas men “discuss”), and generally talk more than men do (Spender, 1984). But in one of the best-known studies of this phenomenon, researchers found that this was more a matter of perception than real difference (Mulac, Incontro, & James, 1985). Two groups of participants were given the same speech. One group was told that a man had authored and presented the speech, while the other was told that a woman had written and given it. Participants who thought the speech was a woman’s perceived it as having more “artistic quality.” Those who believed it was a man’s saw the speech as having more “dynamism.” Participants also described the “man’s” language as strong, active, and aggressive, and the “woman’s” language as pleasing, sweet, and beautiful, despite the fact that the speeches were identical.

focus on CULTURE: Perceiving Race

Perceiving Race

Race is a way we classify people based on common ancestry or descent and is almost entirely judged by physical features (Lustig & Koester, 2006). Once we perceive race, other perceptual judgments follow, most notably the assignment of people to ingrouper versus outgrouper status (Brewer, 1999). People we perceive as being the “same race” we see as being ingroupers. Their communication is perceived more positively than the communication of people of “other races,” and we’re more likely to make positive attributions about their behavior.

Not surprisingly, the perception of racial categories is more salient for people who suffer racial discrimination than for those who don’t. Consider the experience of Canadian professor Tara Goldstein (2001). She asked students in her teacher education class to sort themselves into “same race” groups for a discussion exercise. Four black women immediately grouped together; several East Asian students did the same. But the white students were perplexed. One shouted, “All Italians—over here!” while another inquired, “Any other students of Celtic ancestry?” One white female approached Dr. Goldstein and said, “I’m not white; I’m Jewish.” Following the exercise, the white students commented that they had never been sorted by their whiteness and didn’t perceive themselves or one another as white.

The concept of whiteness has been investigated only recently. Whiteness can often seem “natural” or “normal” to individuals who are white, but for scholars interested in whiteness and for people of color, it means privilege. In her book White Privilege, Peggy McIntosh (1999) lists 26 privileges that she largely takes for granted and that result from her skin color. For example, as a white person, McIntosh is able to swear, dress in secondhand clothes, or not answer e-mail without having members of her race or other races attribute these behaviors to bad morals, poverty, or computer illiteracy. This perception of verbal and nonverbal communication may seem mundane, but as McIntosh says, it is part of white privilege, “an invisible package of unearned assets which I can count on cashing in each day, but about which I was meant to remain oblivious” (p. 79).

discussion questions

What race do you identify with? How does your race affect your perception of ingrouper versus outgrouper communication? How does your race affect other people’s perception of your communication?

Is race an ethical way to perceive how others communicate? Do you think some races have more or less privilege in their interpersonal communication? If so, why?

Given our tendency to presume broad gender differences in communication, can we improve the accuracy of our perception? Yes, if we challenge the assumptions we make about gender and if we remind ourselves that both genders’ approaches to communication are more similar than different. The next time you find yourself thinking, “Oh, she said that because she’s a woman” or “He sees things that way because he is a man,” question your perception. Are these people really communicating differently because of their gender, or are you simply perceiving them as different based on your beliefs about their gender?

PERCEPTION AND PERSONALITY

When you think about the star of a hit television show, a cartoon aardvark isn’t usually the first thing to come to mind. But as any one of the 10 million weekly viewers of PBS’s Arthur will tell you, the appeal of the show is more than just the title character. It is the breadth of personalities displayed across the entire cast, allowing us to link each of them to people in our own lives. Sue Ellen loves art, music, and world culture, while the Brain is studious, meticulous, and responsible. Francine loves interacting with people, especially while playing sports, and Buster is laid-back, warm, and friendly to just about everyone. D.W. drives Arthur crazy with her moods, obsessions, and tantrums, while Arthur—at the center of it all—combines all of these traits into one appealing, complicated package.

| Personality Trait | Description |

|---|---|

| Openness | The degree to which a person is willing to consider new ideas and take an interest in culture. People high in openness are more imaginative, creative, and interested in seeking out new experiences than those low in openness. |

| Conscientiousness | The degree to which a person is organized and persistent in pursuing goals. People high in conscientiousness are methodical, well organized, and dutiful; those low in conscientiousness are less careful, less focused, and more easily distracted. Also known as dependability. |

| Extraversion | The degree to which a person is interested in interacting regularly with others and actively seeks out interpersonal encounters. People high in extraversion are outgoing and sociable; those low in extraversion are quiet and reserved. |

| Agreeableness | The degree to which a person is trusting, friendly, and cooperative. People low in agreeableness are aggressive, suspicious, and uncooperative. Also known as friendliness. |

| Neuroticism | The degree to which a person experiences negative thoughts about oneself. People high in neuroticism are prone to insecurity and emotional distress; people low in neuroticism are relaxed, less emotional, and less prone to distress. Also known as emotional stability. |

In the show Arthur, we see embodied in animated form the various dispositions that populate our real-world interpersonal lives. And when we think of these people and their personalities, visceral reactions are commonly evoked. We like, loathe, or even love people based on our perception of their personalities and how their personalities mesh with our own.

Clearly, personality shapes how we perceive others, but what exactly is it? Personality is an individual’s characteristic way of thinking, feeling, and acting, based on the traits—enduring motives and impulses—that he or she possesses (McCrae & Costa, 2001). Contemporary psychologists argue that although thousands of personalities exist, each is composed of only five primary traits, referred to as the “Big Five” (John, 1990). These are openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism (see Table 3.2 on p. 84). A simple way to remember them is the acronym OCEAN. The degree to which a person possesses each of the Big Five traits determines his or her personality (McCrae, 2001).

self-reflection

What personality traits do you like in yourself? When you see these traits in others, how does that impact your communication toward them? How do you perceive people who possess traits you don’t like in yourself? How do these perceptions affect your relationships with them?

Prioritizing Our Own Traits When Perceiving Others Our perception of others is strongly guided by the personality traits we see in ourselves and how we evaluate these traits. If you’re an extravert, for example, another person’s extraversion becomes salient to you when you’re communicating with him or her. Likewise, if you pride yourself on being friendly, other people’s friendliness becomes your perceptual focus.

But it’s not just a matter of focusing on certain traits to the exclusion of others. We evaluate people positively or negatively in accordance with how we feel about our own traits. We typically like in others the same traits we like in ourselves, and we dislike in others the traits that we dislike in ourselves.

To avoid this preoccupation with your own traits, carefully observe how you focus on other people’s traits and how your evaluation of these traits reflects your own feelings about yourself. Strive to perceive people broadly, taking into consideration all of their traits and not just the positive or negative ones that you share. Then evaluate them and communicate with them independently of your own positive and negative self-evaluations.

Generalizing from the Traits We Know Another effect that personality has on perception is the presumption that because a person is high or low in a certain trait, he or she must be high or low in other traits. For example, say that I introduce you to a friend of mine, Shoshanna. Within the first minute of interaction, you perceive her as highly friendly. Based on your perception of her high friendliness, you’ll likely also presume that she is highly extraverted, simply because high friendliness and high extraversion intuitively seem to go together. If people you’ve known in the past who were highly friendly and extraverted also were highly open, you may go further, perceiving Shoshanna as highly open as well.

Your perception of Shoshanna was created using implicit personality theories, personal beliefs about different types of personalities and the ways in which traits cluster together (Bruner & Taguiri, 1954). When we meet people for the first time, we use implicit personality theories to perceive just a little about an individual’s personality and then presume a great deal more, making us feel that we know the person and helping to reduce uncertainty. At the same time, making presumptions about people’s personalities is risky. Presuming that someone is high or low in one trait because he or she is high or low in others can lead you to communicate incompetently. For example, if you presume that Shoshanna is high in openness, you might mistakenly presume she has certain political or cultural beliefs, leading you to say things to her that cut directly against her actual values, such as, “Don’t you just hate when people mix religion and politics?” However, Shoshanna might respond with, “No, actually I think that government should be based on scriptural principles.”