What Is Culture?

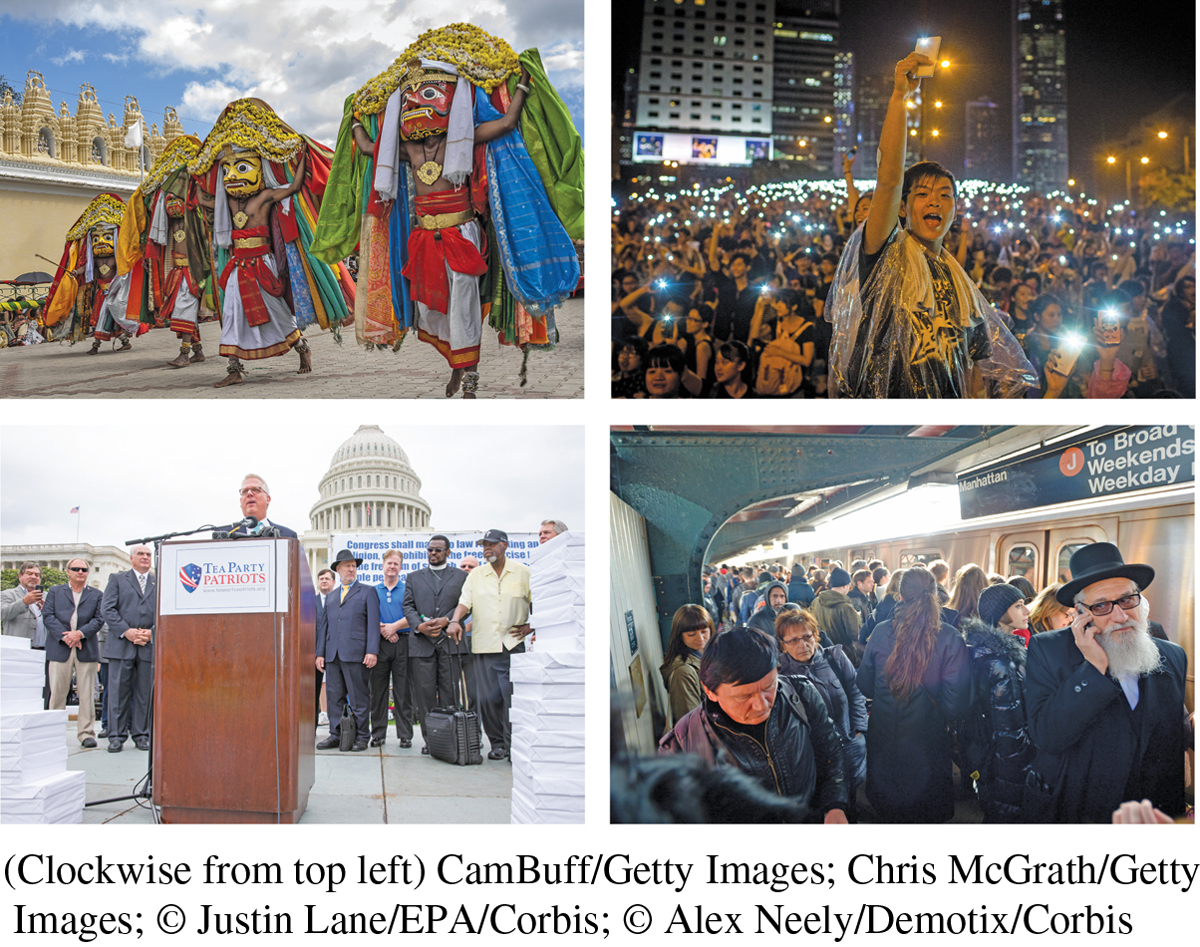

As our world gets more diverse, understanding culture and cultural differences in interpersonal communication becomes increasingly important. Consider, for example, cultural diversity in the United States. In 2012, for example, the Census Bureau reported that for the first time in history, more than 50 percent of all U.S. births were nonwhite—including Latino, Asian, African American, and mixed-raced children. This means that nonwhite minorities, as a group, are now the majority. International student enrollments in the United States are also on the rise (Institute of International Education, 2011); consequently, your college classmates are just as likely to be from Singapore as from Seattle. Plus, with all the digital devices available, we have easy access to people around the world. This enables us to conduct business and personal relationships on a global level in a way never possible before. As just one example, I routinely Skype with faculty friends in Korea, the Netherlands, France, and Brazil, although keeping track of the time differences is a challenge! As our daily encounters increasingly cross cultural lines, making us more aware of diversity, the question arises: what exactly is culture? Understanding the nature of culture, how it’s different from co-cultures, and how prejudice can impact our interpersonal communication is the starting point for building intercultural communication competence.

CULTURE DEFINED

As defined in Chapter 1, culture is an established, coherent set of beliefs, attitudes, values, and practices shared by a large group of people (Keesing, 1974). Culture includes many types of influences, such as your nationality, ethnicity, religion, gender, sexual orientation, physical abilities, and even age. But what really makes a culture a “culture” is that it’s widely shared. This happens because cultures are learned, communicated, layered, and lived.

self-reflection

Recall a childhood memory of learning about your culture. What tradition or belief did you learn about? Who taught you this lesson? What impact did this have on your understanding of your culture?

Culture Is Learned You learn your cultural beliefs, attitudes, and values from many sources, including your parents, teachers, religious leaders, peers, and the mass media (Gudykunst & Kim, 2003). This process begins at birth, through customs such as choosing a newborn’s name, taking part in religious ceremonies, and selecting godparents or other special guardians. As you mature, you learn deeper aspects of your culture, including the history behind certain traditions: why unleavened bread is eaten during Jewish Passover, for instance, or why certain days are more auspicious than others. When I was young, Halloween was all about trick-or-treating and competing with my brother to see who could get the most candy. But as I aged, my parents shared with me the rich history behind such practices, and how they date back to ancient Celtic celebrations of the new year. You also learn how to participate in rituals—everything from blowing out the candles on a birthday cake to lighting Advent candles. In most societies, teaching children to understand, respect, and practice their culture is considered an essential part of child rearing. When I raised my three boys, I shared with them the history of Halloween just as my parents had done with me.

self-reflection

Have you ever encountered a situation in which your communication behaviors and those of someone from a different culture clashed? How did you respond? What cultural factors played a role? Were you able to overcome the difficulty?

Culture Is Communicated Each culture has its own practices regarding how to communicate, and these can widely differ from one another (Whorf, 1952). To illustrate, when I was an undergraduate, I became good friends with Amid, who was originally from Iran. Despite our friendship, our interpersonal communication behaviors would often clash because of cultural differences. For example, in his culture, he was taught, when talking with friends, “stand close enough to smell their breath.” I, on the other hand, grew up in the United States, where expectations on personal distance are to stay at least an arm’s length away, even with friends. (We’ll discuss nonverbal communication, including personal space, in more detail in Chapter 8.) So, whenever Amid and I would talk, he would sidle closer, coming to within a few inches of my face. I would then step back, at which point he would step closer, and I would step back—resulting in a little “dance of distance”! At this point, we’d usually notice what we were doing and laugh about it.

Culture Is Layered Many of us belong to more than one culture. This means we experience multiple layers of culture simultaneously, as various traditions, heritages, and practices are recognized and held as important. My family heritage, for example, is Scottish, Irish, and Swiss German. But each of us prioritizes the different layers of our ancestry differently. My brother takes our Scottish ancestry very seriously, attending the Scottish Highland Games in Washington State (where he lives) every year. My mom, on the other hand, thinks of herself as primarily Swiss German, and even made a pilgrimage to our hereditary hometown of Breitenbach, in Switzerland. In contrast, I think of myself as Irish (largely because I love Irish music!), and I celebrate various Irish holidays. My dad keeps us all grounded by reminding us that we’re really all “mutts,” and that all of these facets of our cultural heritage are important.

Culture Is Lived Culture affects everything about how you live your life. It influences the neighborhoods you live in; the means of transportation you use; the way you think, dress, talk, and even eat. Its impact runs so deep that it is often taken for granted. At the same time, culture is often a great source of personal pride. Many people consciously live in ways that celebrate their cultural heritage through such behaviors as wearing a Muslim hijab, placing a Mexican flag decal on their car, or greeting others with the Thai gesture of the Wai (hands joined in prayer, heads bowed).