Emotion Displays, Masculinity Versus Femininity, and Views of Time

148

EMOTION DISPLAYS

In all cultures, norms exist regarding how people should and shouldn’t express emotion. These norms are called display rules: guidelines for when, where, and how to manage emotion displays appropriately (Ekman & Friesen, 1975). Display rules govern very specific aspects of your nonverbal communication, such as how broadly you should smile, whether or not you should scowl when angry, and the appropriateness of shouting out loud in public when you’re excited. (For more discussion of this, see Chapter 8 on nonverbal communication.) Children learn such display rules and, over time, internalize them to the point where following these rules seems normal. This is why you likely think of the way you express emotion as natural, rather than as something that has been socialized into you through your culture (Hayes & Metts, 2008).

skillspractice

Negotiating Display Rules

Learn how to competently manage emotions in various situations and encounters.

Consider context. Keep in mind that specific contexts also have display rules. For example, some workplaces may demand strict emotional control.

Observe others. Consider how your communication partners regulate emotion, being careful not to judge them as “cold” or “overly emotional.”

Adapt accordingly. Ensure that your communication mirrors what is appropriate for the context and your communication partners.

Evaluate your behavior. Consider how your displays of emotion may have helped or hindered achievement of your desired outcomes.

Because of differences in socialization and traditions, display rules vary across cultures (Soto, Levenson, & Ebling, 2005). Take the two fastest-growing ethnic groups in the United States—Mexican Americans and Chinese Americans (Buriel & De Ment, 1997). In traditional Chinese culture, people prioritize emotional control and moderation; intense emotions are considered dangerous and are even thought to cause illness (Wu & Tseng, 1985). This belief shapes communication in close relationships. Chinese American couples don’t openly express positive emotions toward each other as often as Euro-American couples do (Tsai & Levenson, 1997). Meanwhile, in traditional Mexican culture, people openly express emotion, even more so than people in Euro-American cultures (Soto et al., 2005). For people of Mexican descent, the experience, expression, and deep discussion of emotions provide some of life’s greatest rewards and satisfactions.

When families immigrate to a new society, the move often provokes tension over which display rules to follow. People more closely oriented to their cultures of origin continue to communicate their emotions in traditional ways. Others—usually the first generation of children born in the new society—may move away from traditional forms of emotional expression (Soto et al., 2005). For example, Chinese Americans who adhere strongly to traditional Chinese culture openly display fewer negative emotions than do those who are Americanized (Soto et al., 2005). Similarly, Mexican Americans with strong ties to traditional Mexican culture express intense negative emotion more openly than do Americanized Mexican Americans.

Keep such differences in mind when interpersonally communicating with others. An emotional expression—such as a loud shout of intense joy—might be considered shocking and inappropriate in some cultures but perfectly normal and natural in others. Similarly, openly crying or wailing loudly with grief at a funeral service might be expected within some cultures and prohibited in others. At the same time, don’t presume that all people from the same culture necessarily share the same expectations. As much as possible, adjust your expression of emotion to match the style of the individuals with whom you’re interacting.

149

MASCULINITY VERSUS FEMININITY

Another dimension along which cultures differ that impacts interpersonal communication is the degree to which masculine, versus feminine, values are emphasized. Masculine cultural values include the accumulation of material wealth as an indicator of success, assertiveness, and personal achievement. Within highly masculine cultures, people are taught that competition is the highest good; people who “win” or who are “the best in their field” are looked up to as heroes. “Beating out the competition” and “having a competitive edge” are emphasized throughout schooling, in politics, and within professional life. So, for example, if you and a coworker who is a single mother both apply for the same promotion—one that will result in a substantial raise—but you decide to withdraw your application because you think she needs the money more than you do, members of a masculine culture would be highly perplexed by your choice.

150

In contrast, feminine cultural values emphasize compassion and cooperation. Within feminine cultures, emphasis is placed on caring for the weak and underprivileged and boosting the quality of life for all people. To borrow from the previous example, members of a feminine culture would greatly respect and admire the decision to bow out of a competition for a promotion to help a coworker whom you judge as having greater need than you.

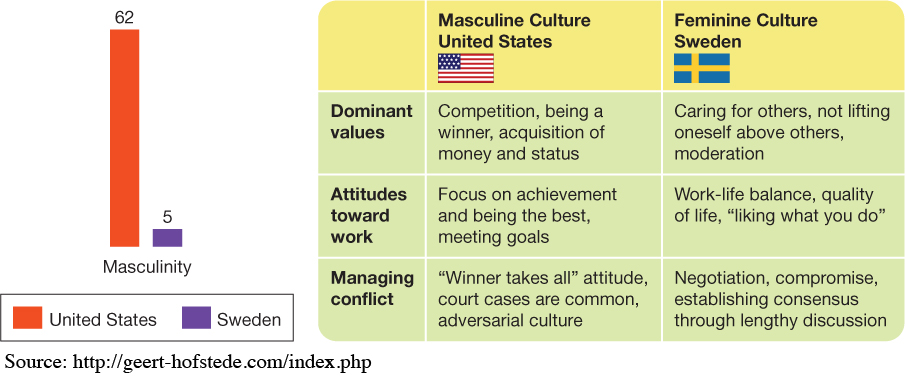

Examples of masculine cultures include Japan, Hungary, Venezuela, and Italy; feminine cultures include Sweden, Norway, the Netherlands, and Denmark. The United States rates as a substantially masculine country (62 out of 100 on the masculinity index), whereas Canada is moderately masculine (around 10 points below the United States). See Figure 5.2 for a comparison of the cultural values in the United States and Sweden.

Importantly, whether a culture is masculine, feminine, or somewhere in between impacts both men and women in very real ways. For example, feminine cultures typically offer lengthy paid or partially paid leaves from work following the birth or adoption of a child—in some cases, for more than a year. Within masculine cultures, such extended leaves would be unimaginable. The masculinity or femininity of a culture also shapes very specific aspects of communication. For example, managers in masculine cultures are expected to be decisive and authoritarian; managers in feminine cultures are expected to focus more on the process of decision making and the achievement of consensus between involved parties.

151

VIEWS OF TIME

Cultures also vary in terms of how people view time. Scholar Edward Hall distinguished between two time orientations: monochronic (M-time) and polychronic (P-time) (1997b). People who have a monochronic time orientation view time as a precious resource. It can be saved, spent, wasted, lost, or made up, and it can even run out. If you’re an M-time person, “spending time” with someone or “making time” in your schedule to share activities with him or her sends the message that you consider that person—and your relationship—important (Hall, 1983). You may view time as a gift you give others to show your affection, or as a tool for punishing someone (“I no longer have time for you”).

People who have a polychronic time orientation don’t view time as a resource to be spent, saved, or guarded. They don’t consider time of day (what time it is) as especially important or relevant to daily activities. Instead, they’re flexible when it comes to time, and they believe that harmonious interaction with others is more important than “being on time” or sticking to a schedule.

Differences in time orientation can create problems when people from different cultures make appointments with each other (Hall, 1983). For example, those with an M-time orientation, such as many Americans, Canadians, Swiss, and Germans, often find it frustrating if P-time people show up for a meeting after the scheduled start time. In P-time cultures, such as those in Arabian, African, Caribbean, and Latin American countries, people think that arriving 30 minutes or more after a meeting’s scheduled start is perfectly acceptable and that it’s OK to change important plans at the last minute.

skillspractice

Understanding Time Orientation

Become more mindful of the way you and your communication partners communicate with time.

Learn about different time orientations. Perhaps your roommate isn’t just a stickler about her bedtime; she may simply be on M-time!

Accommodate others. Don’t rush your P-time grandmother off the phone when she’s telling you about her week. Call her when your schedule allows for a leisurely conversation.

Avoid criticizing. Time is just one dimension of intercultural communication. Your high- or low-context or individualistic or collectivistic communication style can confuse someone, as much as you can be frustrated by another’s time orientation.

You can boost your intercultural competence by understanding other people’s views of time. Learn about the time orientation of a destination or country before you travel there. For example, before my family and I traveled to St. Martin in the French West Indies, we learned that it was a P-time culture. So, at the end of our trip, I planned accordingly. When we needed a cab to pick us up at the hotel at 10:30 in the morning, I told the cabdriver to be there by 9:45. Sure enough, at around 10:25 he rolled up—almost exactly the amount of lateness that I had anticipated!

Also, respect others’ time orientations. If you’re an M-time person interacting with a P-time individual, don’t suddenly dash off to your next appointment because you feel you have to stick to your schedule. Your communication partner will likely think you’re rude. If you’re a P-time person interacting with an M-time partner, realize that he or she may get impatient with a long, leisurely conversation or see a late arrival to a meeting as inconsiderate. In addition, avoid criticizing or complaining about behaviors that stem from other people’s time orientations. Instead, accept the fact that people view time differently, and be willing to adapt your own expectations and behaviors accordingly.