Understanding Listening Styles

“If the person you are talking to doesn’t appear to be listening, be patient. It may simply be that he has a small piece of fluff in his ear.”—A. A. Milne

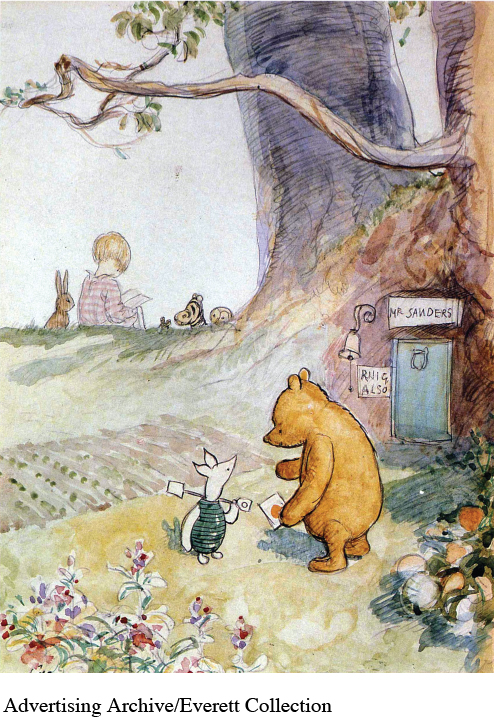

In the original Winnie-the-Pooh books, the character of Christopher Robin is a consistently empathic listener to whom all the other characters turn for comfort. Whenever Pooh worries about his own ineptitude (“I am a bear of no brain at all”), Christopher Robin listens and then offers support: “You’re the best bear in all the world.” In contrast, Owl is Mr. Analytical. He prides himself on being wise and encourages others to bring detailed information and dilemmas to him, even if he often doesn’t know the answers. Meanwhile, Rabbit just wants people to get to the point, so he can act on it. He interrupts them if they stray from the purpose of the conversation, pointedly asking, “Does it matter?” Tigger, though good natured, never seems to have the time to listen. When the group goes adventuring, Tigger urges the others to “Come on!” and then leaves without waiting to hear their responses.

Winnie-the-Pooh is a billion-dollar-a-year industry, and one of the few fictional characters to have a star on the Hollywood walk of fame.2 Books about him have been translated into 34 languages. But at the heart of A. A. Milne’s stories about Edward Bear (Pooh’s real name) is a cast of characters who each have very different listening styles.

FOUR LISTENING STYLES

Like the characters in Milne’s beloved tales, we all tend to experience habitual patterns of listening behaviors, known as listening styles (Barker & Watson, 2000), which reflect our attitudes, beliefs, and predispositions about listening. In general, four different listening styles exist (Bodie & Worthington, 2010). Action-oriented listeners want brief, to-the-point, and accurate messages from others—information they can then use to make decisions or initiate courses of action. Action-oriented listeners can grow impatient when communicating with people they perceive as disorganized, long-winded, or imprecise. For example, when faced with an upset spouse, an action-oriented listener would want information about what caused the problem, so that a solution could be generated. He or she would be less interested in hearing elaborate details of the spouse’s feelings.

Time-oriented listeners prefer brief and concise encounters. They tend to let others know in advance exactly how much time they have available for each conversation. Time-oriented listeners want to stick to their allotted schedules and often look at clocks, watches, or phones to ensure this is the case (Bodie & Worthington, 2010).

In contrast, people-oriented listeners view listening as an opportunity to establish commonalities between themselves and others. When asked to identify the most important part of effective listening, people-oriented listeners cite concern for other people’s emotions. They strive to demonstrate empathy when listening by using positive feedback and offering supportive responses. People-oriented listeners tend to score high on measures of extraversion and overall communication competence (Villaume & Bodie, 2007).

Content-oriented listeners prefer to be intellectually challenged by the messages they receive during interpersonal encounters and enjoy receiving complex and provocative information. Content-oriented listeners often take time to carefully evaluate facts and details before forming an opinion about information they’ve heard. Of the four listening styles, content-oriented listeners are the most likely to ask speakers clarifying or challenging questions (Bodie & Worthington, 2010).

Our listening styles are learned early in life by observation and interaction with parents and caregivers, gender socialization (learning about how men and women are “supposed” to listen), and cultural values regarding what counts as effective listening (Barker & Watson, 2000). Through constant practice, our listening styles become deeply entrenched as part of our communication routines. As a consequence, most of us use only one or two listening styles in all of our interpersonal interactions (Chesebro, 1999). One study found that 36.1 percent of people reported exclusively using a single listening style across all their interpersonal encounters; an additional 24.8 percent reported that they never use more than two listening styles (Watson, Barber, & Weaver, 1995). We also resist attempts to switch from our dominant styles, even when those styles are ill-suited to the situation at hand. This can cause others to perceive us as insensitive, inflexible, and even incompetent communicators.

To be an active listener, you have to use all four styles, so you can strategically deploy each of them as needed. For example, in situations in which your primary listening function is to provide emotional support—when loved ones want to discuss feelings or turn to you for comfort—you should quickly adopt a people-oriented listening style (Barker & Watson, 2000). Studies document that use of a people-oriented listening style substantially boosts others’ perceptions of your interpersonal sensitivity (Chesebro, 1999). In such encounters, use of a content-, time-, or action-oriented style would likely be perceived as incompetent.

By contrast, if your dominant listening function is to comprehend—for instance, during a training session at work—you’ll need to use a content-oriented listening style. Similarly, if you’re talking with someone who is running late for an appointment or who has to make a decision quickly, you should use a more time- or action-oriented style. For additional tips on how to improve your active listening, see Table 6.1.

| To be a more active listener, try these strategies: |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

GENDER DIFFERENCES IN LISTENING STYLES

Studies have found that women and men differ in their listening-style preferences and practices (Watson et al., 1995). Women are more likely than men to use people-oriented and content-oriented listening styles, and men are more likely to use time-oriented and action-oriented styles. These findings have led researchers to conclude that men (in general) tend to have a task-oriented and hurried approach to listening, whereas women perceive listening as an intellectual, an emotional, and, ultimately, a relational activity.

self-reflection

Do your preferred listening styles match research on male–female differences? How have your listening styles affected your communication with people of the same gender? the opposite gender?

Keeping these differences in mind during interpersonal encounters is an important part of active listening. When interacting with men, observe the listening styles they display, and adapt your style to match theirs. Don’t be surprised if time- or action-oriented styles emerge the most. When conversing with women, follow the same pattern, carefully watching their listening styles and adjusting your style accordingly. Be prepared to quickly shift to more people- or content-oriented styles if needed. But don’t automatically assume that just because a person is female or male means that she or he will always listen—or expect you to listen—in certain ways. Take your cue from the person you are talking with.

focus on CULTURE: Men Just Don’t Listen!

Men Just Don’t Listen!

The belief that men are listening-challenged is widespread. Linguist Deborah Tannen (1990a) posits that the perception of male listening incompetence stems from several sources, including men facing away rather than toward people when listening, making dismissive comments in response to disclosures, changing conversational topics too rapidly, and listening silently rather than providing vocal back-channel cues such as “Mm-hmm” and “Yeah.” But at a broader level, Tannen believes that male listening is symptomatic of cultural differences between the sexes. As she elaborates,

For women, intimacy is the fabric of relationships, and talk is the thread from which it is woven. Bonds between boys are based less on talking, more on doing things together. Boys’ groups are more hierarchical, so boys must struggle to avoid the subordinate position. This may play a role in women’s complaints that men don’t listen. Some men really don’t like to listen, because being the listener makes them feel one-down, like a child listening to adults.

What’s the solution? Tannen recommends that men and women view “their differences as cross-cultural rather than right or wrong.”

Cognitive scientists and communication scholars offer an alternative view. Analyzing data from dozens of studies, brain researcher Daniel Voyer (2011) found only small differences between the sexes in their listening, so small that they can’t be generalized to individual women and men. Communication researchers Daena Goldsmith and Patricia Fulfs (1999) examined every sex difference suggested by Tannen and found no scientific evidence supporting them. After reviewing existing communication studies, scholar Kathryn Dindia (2006) agreed with Fulfs and Goldsmith, concluding that “the empirical evidence indicates that differences between women and men are minimal by any measure.” Dindia noted that “North American girls and boys are raised in the same culture, but that culture teaches them that they are very different. In spite of this, they turn out remarkably similar.” Dindia goes on to suggest a different metaphor for thinking about sex differences. When it comes to interpersonal communication and listening, “Men are from North Dakota, women are from South Dakota. Women and men do not come from different planets or different cultures, they come from neighboring states.”

discussion questions

Do men and women grow up in different communication cultures, as Tannen suggests? Or, as Dindia argues, is it the same culture, in which they are repeatedly taught about how different they are?

In your experience, do men and women listen differently? If so, what differences have you observed? Is one sex inherently better at listening than the other, or is it a matter of individual style rather than a general sex difference?

CULTURE AND LISTENING STYLES

Culture powerfully shapes the use and perception of listening styles. What’s considered effective listening by one culture is often perceived as ineffective by others, something you should always keep in mind when communicating with people from other cultures. For example, in individualistic cultures such as the United States and Canada (and particularly in the American workplace), time-oriented and action-oriented listening styles dominate. People often approach conversations with an emphasis on time limits (“I have only 10 minutes to talk”). Many people also feel and express frustration if others don’t communicate their ideas efficiently (“Just say it!”).

The value that people from individualistic cultures put on time and efficiency—something we discuss in Chapter 5—frequently places them at odds with people from other cultures. In collectivistic cultures, people- and content-oriented listening is emphasized. In many East Asian countries, for example, Confucian teachings admonish followers to pay close attention when listening, display sensitivity to others’ feelings, and be prepared to assimilate complex information—hallmarks of people- and content-oriented listening styles (Chen & Chung, 1997). Studies have found that students from outside the United States view Americans as less willing and patient listeners than individuals who come from Africa, Asia, South America, and southern Europe—regions that emphasize people-oriented listening (Wolvin, 1987).