Functions of Verbal Communication

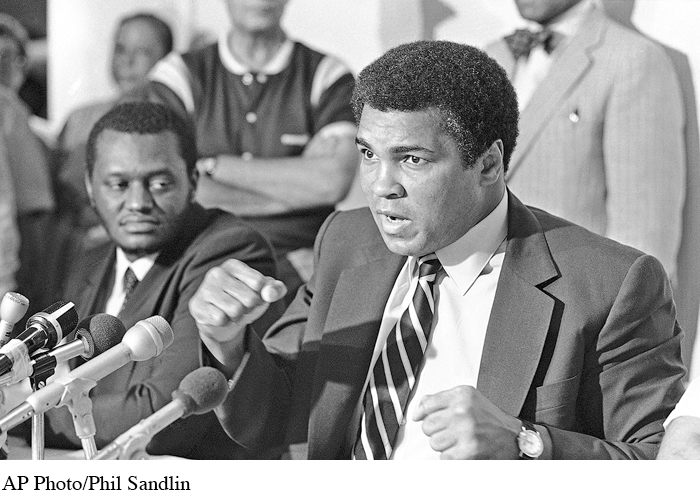

He was crowned Sportsman of the Century by Sports Illustrated, and Sports Personality of the Century by the BBC.3 He is considered by many to be the greatest boxer of all time, a fact reflected in his nickname, the Greatest. He certainly was the most verbal. Muhammad Ali made a name for himself early in his career by poetically boasting about his abilities (“Your hands can’t hit what your eyes can’t see!”) and trash-talking his opponents. “I’m going to float like a butterfly and sting like a bee,” he told then champion Sonny Liston, whom Ali dubbed “the big ugly bear” before defeating him to claim the World Heavyweight title. Ali was just as verbal outside the boxing ring. Early in his professional career, he embraced Islam and subsequently abandoned his birth name of Cassius Clay because the surname came from his ancestors’ slave owners. Years before public sentiment joined him, Ali spoke out repeatedly against the Vietnam War. His refusal to participate in the military draft cost him both his world title and his boxing license (both of which were eventually reinstated). Years later, he continues to be outspoken on behalf of humanitarian causes. His work with UN hunger relief organizations has helped feed tens of millions of people (“Service to others is the rent you pay for your room here on earth”), and he was a United Nations Messenger of Peace and a recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Whether in the boxing ring or on a charity mission, he has used his prowess with verbal communication to achieve his goals and dreams.

We all use verbal communication to serve many different functions in our daily lives. Let’s examine six of the most important of these, all of which strongly influence our interpersonal communication and relationships.

SHARING MEANING

The most obvious function verbal communication serves is enabling us to share meanings with others during interpersonal encounters. When you use language to verbally communicate, you share two kinds of meanings. The first is the literal meaning of your words, as agreed on by members of your culture, known as denotative meaning. Denotative meaning is what you find in dictionaries—for example, the word bear means “any of a family (Ursidae of the order Carnivora) of large heavy mammals of America and Eurasia that have long shaggy hair” (Merriam-Webster Dictionary, 2011). When Ali called Sonny Liston “the big ugly bear,” he knew Liston would understand the denotative meanings of his words and interpret them as an insult.

But when we verbally communicate, we also exchange connotative meaning: additional understandings of a word’s meaning based on the situation and the knowledge we and our communication partners share. Connotative meaning is implied, suggested, or hinted at by the words you choose while communicating with others. Say, for example, that your romantic partner has a large stuffed teddy bear that, despite its weathered and worn appearance, is your partner’s most prized childhood possession. To convey your love and adoration for your partner, you might say, “You’re my big ugly bear.” In doing so, you certainly don’t mean that your lover is big, ugly, or bearlike in appearance! Instead, you rely on your partner understanding your implied link to his or her treasured object (the connotative meaning). Relationship intimacy plays a major role in shaping how we use and interpret connotative meanings while communicating with others (Hall, 1997a): people who know each other extremely well can convey connotative meanings accurately to one another.

SHAPING THOUGHT

In addition to enabling us to share meaning during interpersonal encounters, verbal communication also shapes our thoughts and perceptions of reality. Feminist scholar Dale Spender (1990) describes the relationship between words and our inner world in this way:

To speak metaphorically, the brain is blind and deaf; it has no direct contact with light or sound. The brain has to interpret: it only deals in symbols and never knows the real thing. And the program for encoding and decoding is set up by the language which we possess. What we see in the world around us depends in large part on our language. (pp. 139–140)

Consider an encounter I had at a family gathering. My 6-year-old niece told me that a female neighbor of hers had helped several children escape a house fire. When I commended the neighbor’s heroism, my niece corrected me. “Girls can’t be heroes,” she scolded. “Only boys can be heroes!” In talking with her further, I discovered she knew of no word representing “brave woman.” Her only exposure to heroine was through her mother’s romantic novels. Not knowing a word for “female bravery,” she considered the concept unfathomable: “The neighbor lady wasn’t a hero; she just saved the kids.”

The idea that language shapes how we think about things was first suggested by researcher Edward Sapir, who conducted an intensive study of Native American languages in the early 1900s. Sapir argued that because language is our primary means of sharing meaning with others, it powerfully affects how we perceive others and our relationships with them (Gumperz & Levinson, 1996). Almost 50 years later, Benjamin Lee Whorf expanded on Sapir’s ideas in what has become known as the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis. Whorf argued that we cannot conceive of that for which we lack a vocabulary—that language quite literally defines the boundaries of our thinking. This view is known as linguistic determinism. As contemporary scholars note, linguistic determinism suggests that our ability to think is “at the mercy” of language (Gumperz & Levinson, 1996). We are mentally constrained by language to think only certain thoughts, and we cannot interpret the world in neutral ways because we always see the world through the lens of our languages.

Both Sapir and Whorf also recognized the dramatic impact that culture has on language. Because language determines our thoughts, and different people from different cultures use different languages, Sapir and Whorf agreed that people from different cultures would perceive and think about the world in very different ways, an effect known as linguistic relativity.

self-reflection

Think about the vocabulary you inherited from your culture for thinking and talking about relationships. What terms exist for describing serious romantic involvements, casual relationships that are sexual, and relationships that are purely platonic? How do these various terms shape your thinking about these relationships?

NAMING

A third important function of verbal communication is naming, creating linguistic symbols for objects. The process of naming is one of humankind’s most profound and unique abilities (Spender, 1984). When we name people, places, objects, and ideas, we create symbols that represent them. We then use these symbols during our interactions with others to communicate meaning about these things. Because of the powerful impact language exerts on our thoughts, the decisions we make about what to name things ultimately determine not just the meanings we exchange but also our perceptions of the people, places, and objects we communicate about. This was why Muhammad Ali decided to abandon his birth name of Cassius Clay. He recognized that our names are the most powerful symbols that define who we are throughout our lives, and he wanted a name that represented his Islamic faith while also renouncing the surname of someone who had, years earlier, enslaved his forebears.

As the Ali example suggests, the issue of naming is especially potent for people who face historical and cultural prejudice, given that others outside the group often label them with derogatory names. Consider the case of gays and lesbians. For many years, gays and lesbians were referred to as “homosexual.” But as scholar Julia Wood (1998) notes, many people shortened homosexual to homo and used the new term as an insult. In response, lesbian and gay activists in the 1960s renamed themselves “gay.” This move also triggered disputes, however. Antigay activists protested the use of a term that traditionally meant “joyous and lively.” Some lesbian activists argued that gay meant only men and was therefore exclusionary to women. Many straight people began using “gay” as an insult in the same manner as earlier epithets. In the 2000s, the inclusive label of “LGBTQ” (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgendered, queer) was created to embrace the entire community. But this name still doesn’t adequately represent many people’s self-impressions. One study identified over a dozen different names that individuals chose for their sexual orientation and gender identity, including “pansexual,” “omnisexual,” and “same-gender loving/SGL” (Morrison & McCornack, 2011). Given the way positive names have been turned to negative in the past, some people reject names for nonstraight sexual orientations altogether. As one study respondent put it, “I don’t use labels—I’m not a can of soup!” (Morrison & McCornack, 2011).

focus on CULTURE: Challenging Traditional Gender Labels

Challenging Traditional Gender Labels

In September 2011, Australia changed its passport policy to allow three gender options on travel documents instead of two: male, female, and indeterminate.4 The goal was to remove discrimination against transgendered persons. As Australian Senator Louise Pratt described, “It’s an important recognition of people’s human rights.” The same month, Pomona College in California revised its student constitution to remove gendered pronouns. “A lot of students do not identify as ‘male’ or ‘female’ and aren’t using the pronouns ‘he’ or ‘she,’ so we are trying to better represent the student body,” said Student Commissioner Sarah Applebaum. “Ideally, this will help promote a more supportive campus for gender-nonconforming, queer, and transgender students.”

These changes are part of a larger cultural trend toward challenging traditional language labels for gender and replacing them with “preferred gender pronouns,” or PGPs—gender names of a person’s own choosing. As Eliza Byard, executive director of the Gay, Lesbian, and Straight Education Network, describes, “More students today than ever are thinking about what gender means and are using language to get away from masculine and feminine gender assumptions.” Some of the more creative PGPs currently in use include “ze,” “hir,” and “hirs.”

Although the use of PGPs is global, the motivation for embracing them is deeply personal. PGPs are a way of using language to authentically capture one’s true gender identity. “This has nothing to do with your sexuality and everything to do with who you feel like inside,” notes Ann Arbor teen Katy Butler. “My PGPs are ‘she,’ ‘her’ and ‘hers’ and sometimes ‘they,’ ‘them’ and ‘theirs.’”

discussion questions

What language label do you most commonly use in reference to your gender? Why do you use this label?

Does this label authentically and comprehensively capture how you think of yourself in terms of gender?