Conflict Endings

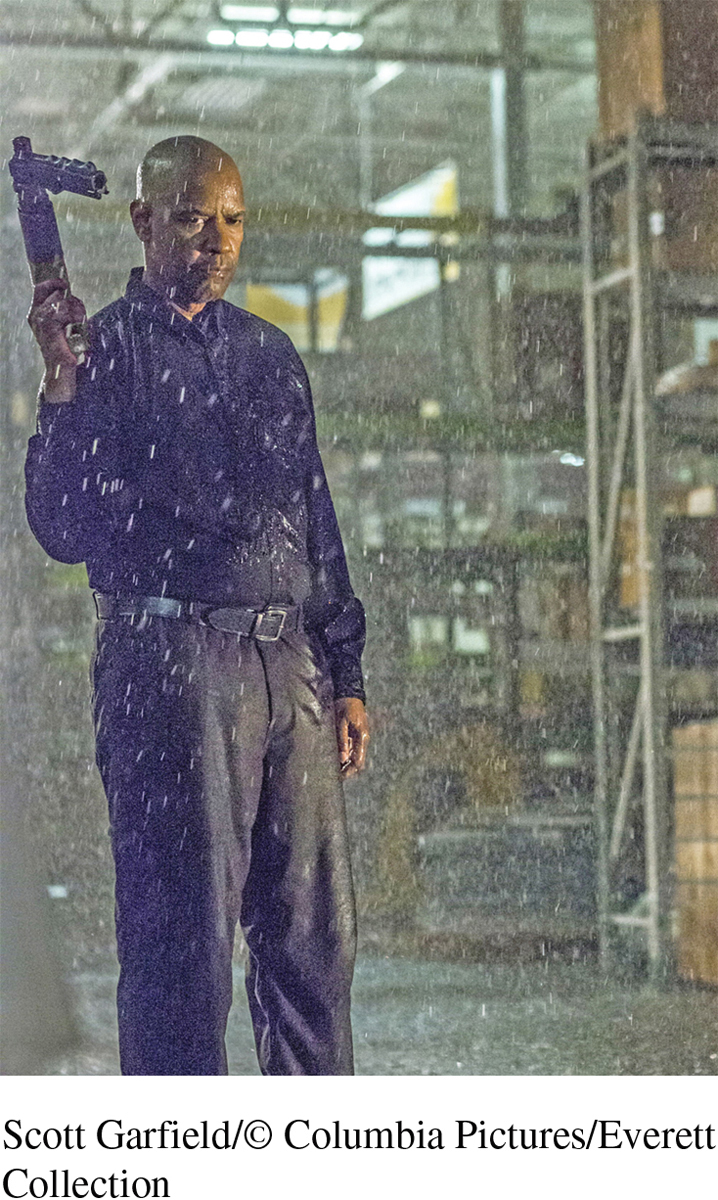

In Antoine Fuqua’s stylish thriller The Equalizer (2014), Denzel Washington plays Robert, a man with a peerless set of fighting skills coupled with a compulsion to see justice done. When Robert learns that a pair of rogue cops are extorting money from the business of a coworker, he films them making their demands. Then he confronts the two men and gives them a choice: return the money they stole or suffer the consequences. The officers refuse, at which point Robert demonstrates the physical consequences of their decision—after which they give back the money.

In the real world, we don’t all have “equalizers” who follow us around, ensuring through cleverness and force that our daily conflicts end in fairness. Nevertheless, our conflicts do end—albeit not always in the ways we wish. For instance, call to mind the most recent serious conflict you experienced, and consider the way it ended. Did one of you “win” and the other “lose”? Were you both left dissatisfied, or were you each pleased with the resolution? More important, were you able to resolve the underlying issue that triggered the disagreement in the first place, or did you merely create a short-term fix?

Given their emotional intensity and the fact that they typically occur in relationships, conflicts conclude more gradually than many people would like. You may arrive at a short-term resolution leading to the immediate end of the conflict. But afterward, you’ll experience long-term outcomes as you remember, ponder, and possibly regret the incident. These outcomes will influence your relationship health and happiness long into the future.

SHORT-TERM CONFLICT RESOLUTIONS

The approach you and your partner choose to handle the conflict usually results in one of five short-term conflict resolutions (Peterson, 2002). First, some conflicts end through separation, the sudden withdrawal of one person from the encounter. This resolution is characteristic of approaching conflict through avoidance. For example, you may be having a disagreement with your mother, when she suddenly hangs up on you. Or you’re discussing a concern with your roommate, when he unexpectedly gets up, walks into his bedroom, and shuts the door behind him. Separation ends the immediate encounter, but it does nothing to solve the underlying incompatibility of goals or the interference that triggered the dispute in the first place.

However, separation isn’t always negative. In some cases, short-term separation may help bring about long-term resolution. For example, if you and your partner have both used competitive or reactive approaches, your conflict may have escalated so much that any further contact may result in irreparable relationship damage. In such cases, temporary separation may help you both cool off, regroup, and consider how to collaborate. You can then come back and work together to better resolve the situation.

Second, domination—akin to Denzel Washington taking down the rogue cops in The Equalizer—occurs when one person gets his or her way by influencing the other to engage in accommodation and abandon goals. Conflicts that end with domination are often called win-lose solutions. The strongest predictor of domination is the power balance in the relationship. In cases in which one person has substantial power over the other, that person will likely prevail.

In some cases, domination may be acceptable. For example, when one person doesn’t feel strongly about achieving his or her goals, being dominated may have few costs. However, domination is destructive when it becomes a chronic pattern and one individual always sacrifices his or her goals to keep the peace. Over time, the consistent abandonment of goals can spawn resentment and hostility. While the accommodating “losers” are silently suffering, the dominating “victors” may think everything is fine because they are used to achieving their goals.

Third, during compromise, both parties change their goals to make them compatible. Often, both people abandon part of their original desires, and neither feels completely happy about it. Compromise typically results from people using a collaborative approach and is most effective in situations in which both people treat each other with respect, have relatively equal power, and don’t consider their clashing goals especially important (Zacchilli et al., 2009). In cases in which the two parties do consider their goals important, however, compromise can foster mutual resentment and regret (Peterson, 2002). Suppose you and your spouse want to spend a weekend away. You planned this getaway for months, but your spouse now wants to attend a two-day workshop that same weekend. A compromise might involve you cutting the trip short by a night and your spouse missing a day of his or her workshop, leaving both of you with substantially less than you originally desired.

skillspractice

Resolving Conflict

Creating better conflict resolutions

When a conflict arises in a close relationship, manage your negative emotions.

Before communicating with your partner, call to mind the consequences of your communication choices.

Employ a collaborative approach, and avoid kitchen-sinking.

As you negotiate solutions, keep your original goals in mind but remain flexible about how they can be attained.

Revisit relationship rules or agreements that triggered the conflict, and consider redefining them in ways that prevent future disputes.

Fourth, through integrative agreements, the two sides preserve and attain their goals by developing a creative solution to their problem. This creates a win-win solution in which both people, using a collaborative conflict approach, benefit from the outcome. To achieve integrative agreements, the parties must remain committed to their individual goals but be flexible in how they achieve them (Pruitt & Carnevale, 1993). An integrative agreement for the weekend-away example might involve rescheduling the weekend so that you and your spouse could enjoy both the vacation and the workshop.

Finally, in cases of especially intense conflict, structural improvements—people agreeing to change the basic rules or understandings that govern their relationship to prevent further conflict—may result. In cases of structural improvement, the conflict itself becomes a vehicle for reshaping the relationship in positive ways—rebalancing power or redefining expectations about who plays what roles in the relationship. Structural improvements are only likely to occur when the people involved control their negative emotions and handle the conflict collaboratively. Suppose your romantic partner keeps in touch with an ex via Facebook. Although you trust your partner, the thought of an ex chatting with him or her on a daily basis, and tracking your relationship through updates and posted photos, drives you crazy. After a jealousy-fueled fight, you and your partner might sit down and collaboratively hash out guidelines for how often and in what ways each of you can communicate with ex-partners, online and off.

LONG-TERM CONFLICT OUTCOMES

After the comparatively short-term phase of conflict resolution, you may begin to ponder the long-term outcomes. In particular, you might consider whether the conflict was truly resolved, and what the dispute’s impact was on your relationship. Research examining long-term conflict outcomes and relationship satisfaction has found that certain approaches for dealing with conflict—in particular, avoidant, reactive, and collaborative approaches—strongly predict relationship quality (Smith et al., 2008; Zacchilli et al., 2009).

The most commonly used conflict approach is avoidance. But because avoidance doesn’t address the goal clash or actions that sparked the conflict, tensions will likely continue. People who use avoidance have lower relationship satisfaction and endure longer and more frequent conflicts than people who don’t avoid (Smith et al., 2008). Consequently, try not to use avoidance unless you’re certain the issue is unimportant. This is a judgment call; sometimes an issue that seems unimportant at the time ends up eating away at you over the long run. When in doubt, communicate directly about the issue.

Far more poisonous to relationship health, however, is reactivity. Individuals who handle conflict by (in effect) throwing tantrums end up substantially less happy in their relationships (Zacchilli et al., 2009). If you or your partner habitually uses reactivity, seriously consider more constructive ways to approach conflict. If you do not, your relationship is likely doomed to dissatisfaction.

In sharp contrast to the negative outcomes of avoidance and reactivity, collaborative approaches generally generate positive long-term outcomes (Smith et al., 2008). People using collaboration tend to resolve their conflicts, report higher satisfaction in their relationships, and experience shorter and fewer disputes. The lesson from this is to always treat others with kindness and respect, and strive to deal with conflict by openly discussing it in a way that emphasizes mutual interests and saves your partner’s face.

If collaborating yields positive long-term outcomes, and avoiding and reacting yield negative ones, what about accommodating and competing? This is difficult to predict. Sometimes you’ll compete and get what you want, the conflict will be resolved, and you’ll be satisfied. Or you’ll compete, the conflict will escalate wildly out of control, and you’ll end up incredibly unsatisfied. Other times you’ll accommodate, the conflict will be resolved, and you’ll be content. Or you’ll accommodate, and the other person will exploit you further, causing you deep discontent. Accommodation and competition are riskier because you can’t count on either as a constructive way to manage conflict for the long term (Peterson, 2002).