What Is Communication?

It was the first minute of the first day of the very first communication class I ever taught. I had just finished defining communication, when a student raised her hand with a puzzled look on her face. “I understand your definition,” she said, “but isn’t this all just common sense?” Her question has stuck with me all these years because it highlights an important starting point for learning about communication. We all come to communication classes with a lifetime of hands-on experience communicating. This leads some to think that they have little new to learn. But personal experience isn’t the same as systematic training. When you’re formally educated about communication, you gain knowledge that goes far beyond your intuition, allowing you to broaden and deepen your skills as a communicator. It’s like any form of expertise. You know how to kick a ball, and you’ve likely done so hundreds, maybe thousands, of times since you were little. But does that mean you have the knowledge and skills to play in the World Cup? Of course not.

My goal for this text is to provide you with the knowledge and skills to make you a World Cup interpersonal communicator. This process begins by answering a basic question: what is communication?

self-reflection

Is good communication just common sense? Does experience communicating always result in better communication? When you think about all the communication and relational challenges you face in your daily life, what do you think would help you improve your communication skills?

DEFINING COMMUNICATION

The National Communication Association (n.d.), a professional organization representing communication teachers and scholars in the United States, defines communication as the process through which “people use messages to generate meanings within and across contexts, cultures, channels, and media.” This definition highlights the five features that characterize communication.

First, communication is a process that unfolds over time through a series of interconnected actions carried out by the participants. For example, your friend tweets that she is going out to a movie, you text her back to see if she wants you to join her, and so forth. Because communication is a process, everything you say and do affects what is said and done in the present and in the future.

Second, those engaged in communication (communicators) use messages to convey meaning. A message is the “package” of information that is transported during communication. When people exchange a series of messages, the result is called an interaction (Watzlawick, Beavin, & Jackson, 1967).

Third, communication occurs in a seemingly endless variety of contexts, or situations. We communicate with others at sporting events, while at work, and in our homes. In each context, a host of factors influences how we communicate, such as how much time we have, how many people are in the vicinity, and whether the setting is personal or professional. Think about it: you probably communicate with your romantic partner differently when you’re in class than when you’re watching a movie at home and snuggling on the couch.

Fourth, people communicate through various channels. A channel is the sensory dimension along which communicators transmit information. Channels can be auditory (sound), visual (sight), tactile (touch), olfactory (scent), or oral (taste). For example, your manager at work smiles while complimenting your job performance (visual and auditory channels). A visually impaired friend reads a message you left her, touching the Braille letters with her fingertips (tactile). Your romantic partner shows up at your house exuding an alluring scent and carrying delicious takeout, which you then share together (olfactory and oral).

Fifth, to transmit information, communicators use a broad range of media—tools for exchanging messages. Consider the various media used by Melissa Seligman and her husband, described in our chapter opener. Webcams, cell phones, texting, e-mail, letters, face-to-face interaction—all of these media and more can be used to communicate. And we often use multiple media channels simultaneously—for example, texting while checking our Facebook page. (See Figure 1.1 for common media forms.)

UNDERSTANDING COMMUNICATION MODELS

Think about all the different ways you communicate each day. You text your sister to check in. You give a speech in your communication class to an engaged audience. You exchange a knowing glance with your best friend at the arrival of someone you mutually dislike. Now reflect on how these forms of communication differ from one another. Sometimes (like when texting) you create messages and send them to receivers, the messages flowing in a single direction, from origin to destination. In other instances (like when speaking in front of your class) you present messages to recipients, and the recipients signal to you that they’ve received and understood them. Still other times (like when you and your best friend exchange a glance) you mutually construct meanings with others, with no one serving as “sender” or “receiver.” These different ways of experiencing communication are reflected in three models that have evolved to describe the communication process: the linear model, the interactive model, and the transactional model. As you will see, each of these models has both strengths and weaknesses. Yet each also captures something unique and useful about the ways you communicate in your daily life.

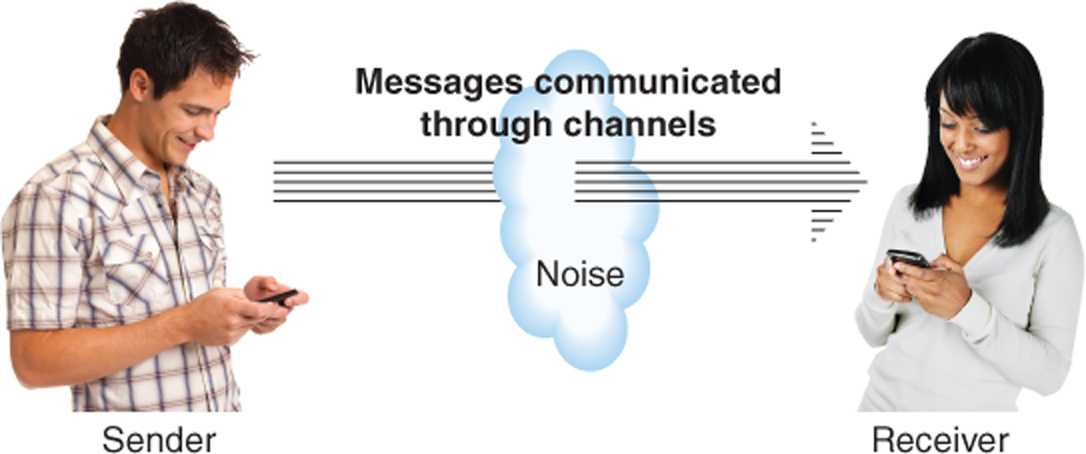

Linear Communication Model According to the linear communication model, communication is an activity in which information flows in one direction, from a starting point to an end point (see Figure 1.2). The linear model contains several components (Lasswell, 1948; Shannon & Weaver, 1949). In addition to a message and a channel, there must be a sender (or senders) of the message—the individual(s) who generates the information to be communicated, packages it into a message, and chooses the channel(s) for sending it. There also is noise—factors in the environment that impede messages from reaching their destination. Noise includes anything that causes our attention to drift from messages—such as poor reception during a cell-phone call or the smell of fresh coffee nearby. Last, there must be a receiver—the person for whom a message is intended and to whom the message is delivered.

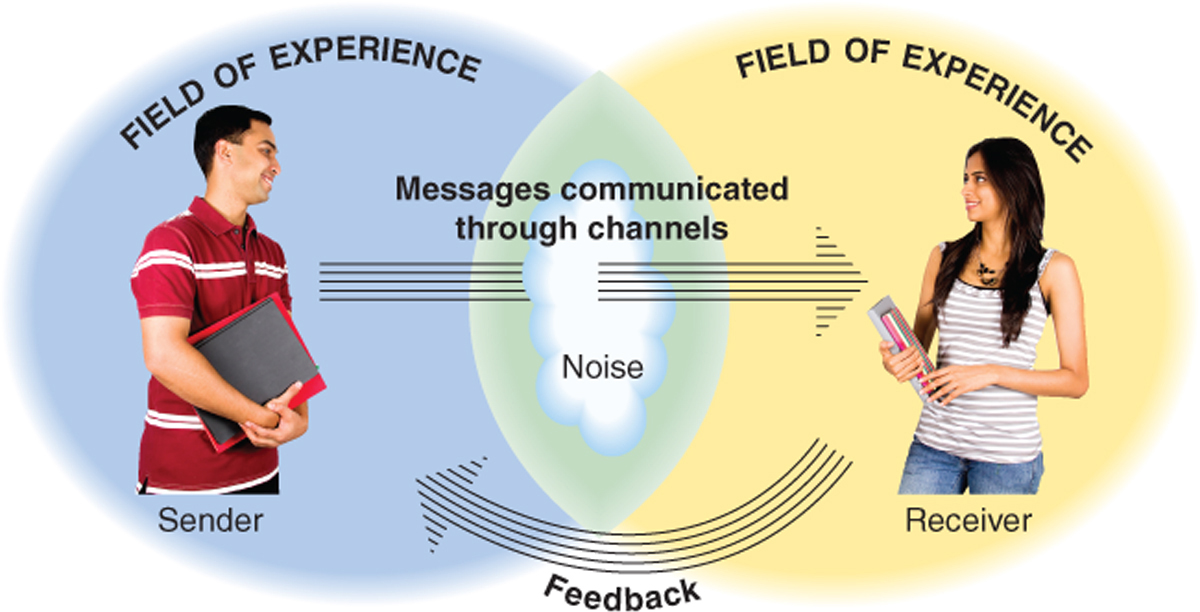

Interactive Communication Model The interactive communication model also views communication as a process involving senders and receivers (see Figure 1.3). However, according to this model, transmission is influenced by two additional factors: feedback and fields of experience (Schramm, 1954). Feedback is composed of the verbal and nonverbal messages (such as eye contact, utterances such as “Uh-huh,” and nodding) that recipients convey to indicate their reaction to communication. Fields of experience consist of the beliefs, attitudes, values, and experiences that each participant brings to a communication event. People with similar fields of experience are more likely to understand each other while communicating than are individuals with dissimilar fields of experience.

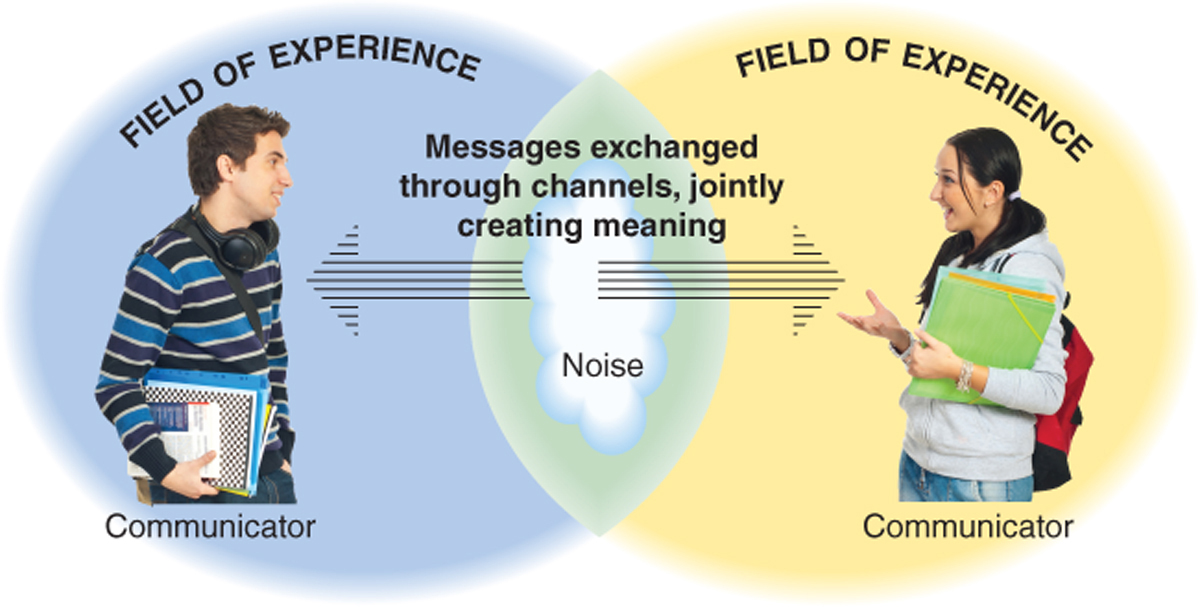

Transactional Communication Model The transactional communication model (see Figure 1.4) suggests that communication is fundamentally multidirectional. That is, each participant equally influences the communication behavior of the other participants (Miller & Steinberg, 1975). From the transactional perspective, there are no “senders” or “receivers.” Instead, all the parties constantly exchange verbal and nonverbal messages and feedback, collaboratively creating meanings (Streek, 1980). This may be something as simple as a shared look between friends, or it may be an animated conversation among close family members in which the people involved seem to know what the others are going to say before it’s said.

| Model | Examples | Strength | Weakness |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linear | Twitter, text and instant-messaging, e-mail, wall posts, scripted public speeches | Simple and straightforward | Doesn’t adequately describe most face-to-face or phone conversations |

| Interactive | Classroom instruction, group presentations, team/coworker meetings | Captures a broad variety of communication forms | Neglects the active role that receivers often play in constructing meaning |

| Transactional | Any encounter (most commonly face-to-face) in which you and others jointly create communication meaning | Intuitively captures what most people think of as interpersonal communication | Doesn’t apply to many forms of online communication, such as Twitter, e-mail, Facebook posts, and text-messaging |

These three models represent an evolution of thought regarding the nature of communication, from a relatively simplistic depiction of communication as a linear process to one that views communication as a complicated process that is mutually crafted. However, these models don’t necessarily represent “good” or “bad” ways of thinking about communication. Instead, each of them is useful for thinking about different forms of communication. See Table 1.1 for more on each model.