Issues in Interpersonal Communication

As we move through the twenty-first century, scholars and students alike increasingly appreciate how important interpersonal communication is in our daily lives and relationships. Moreover, they’re recognizing the impact of societal changes, such as diversity and technological innovation. To ensure that the field stays current with social trends, communication scholars have begun exploring the issues of culture, gender and sexual orientation, online communication, and the dark side of interpersonal relationships.

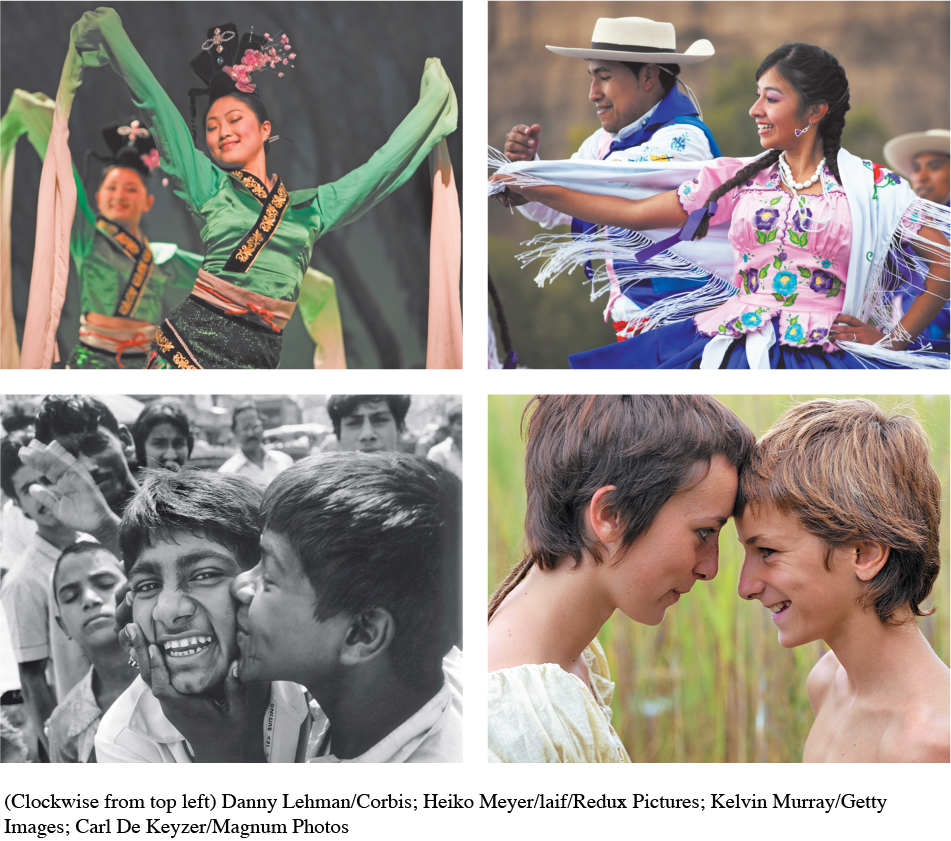

CULTURE

In this text, we define culture broadly and inclusively as an established, coherent set of beliefs, attitudes, values, and practices shared by a large group of people (Keesing, 1974). Culture includes many different types of large-group influences, such as nationality, ethnicity, religion, gender, sexual orientation, physical and mental abilities, and even age. We learn our cultural beliefs, attitudes, and values from parents, teachers, religious leaders, peers, and the mass media (Gudykunst & Kim, 2003). As our world gets more diverse, scholars and students must consider cultural differences when discussing interpersonal communication theory and research, and how communication skills can be improved.

Throughout this book, and particularly in Chapter 5, we examine differences and similarities across cultures and consider their implications for interpersonal communication. As we cover this material, critically examine the role that culture plays in your own interpersonal communication and relationships.

GENDER AND SEXUAL ORIENTATION

Gender consists of social, psychological, and cultural traits generally associated with one sex or the other (Canary, Emmers-Sommer, & Faulkner, 1997). Unlike biological sex, which we’re born with, gender is largely learned. Gender influences how people communicate interpersonally, but scholars disagree about how. For example, you may have read in popular magazines or heard on TV that women are more “open” communicators than men, and that men “have difficulty communicating their feelings.” But when these beliefs are compared with research and theory on gender and interpersonal communication, it turns out that differences (and similarities) between men and women are more complicated than the popular stereotypes suggest. Throughout this book, we discuss such stereotypes and look at scholarly research on the impact of gender on interpersonal communication.

Each of us also possesses a sexual orientation: an enduring emotional, romantic, sexual, or affectionate attraction to others that exists along a continuum ranging from exclusive homosexuality to exclusive heterosexuality and that includes various forms of bisexuality (APA Online, n.d.). You may have heard that gays and lesbians communicate in ways different from “straights” or that each group builds, maintains, and ends relationships in distinct ways. But as with common beliefs about gender, research shows that same-gender and opposite-gender relationships are formed, maintained, and dissolved in similar ways. We also discuss these assumptions about sexual orientation throughout this text.

ONLINE COMMUNICATION

Radical changes in communication technology have had a profound effect on our ability to interpersonally communicate. Mobile devices keep us in almost constant contact with friends, family members, colleagues, and romantic partners. Our ability to communicate easily and frequently, even when separated by geographic distance, is further enhanced through online communication. In this book, we treat such technologies as tools for connecting people interpersonally—tools that are now thoroughly integrated into our lives. In each chapter, you’ll find frequent mention of these technologies as they relate to the chapter’s specific topics.

THE DARK SIDE OF INTERPERSONAL RELATIONSHIPS

Interpersonal communication strongly influences the quality of our interpersonal relationships, and the quality of those relationships in turn affects how we feel about our lives. When our involvements with lovers, family, friends, and coworkers are satisfying and healthy, we feel happier in general (Myers, 2002). But the fact that relationships can bring us joy obscures the fact that relationships, and the interpersonal communication that occurs within them, can often be destructive.

In studying interpersonal communication, you can learn much by looking beyond constructive encounters to the types of damaging exchanges that occur all too frequently in life. The greatest challenges to your interpersonal communication skills lie not in communicating competently when it is easy to do so but in practicing competent interpersonal communication when doing so is difficult. Throughout the text, we will discuss many of the negative situations that you may experience, as well as recommendations for how to deal with them.