Presenting Your Self

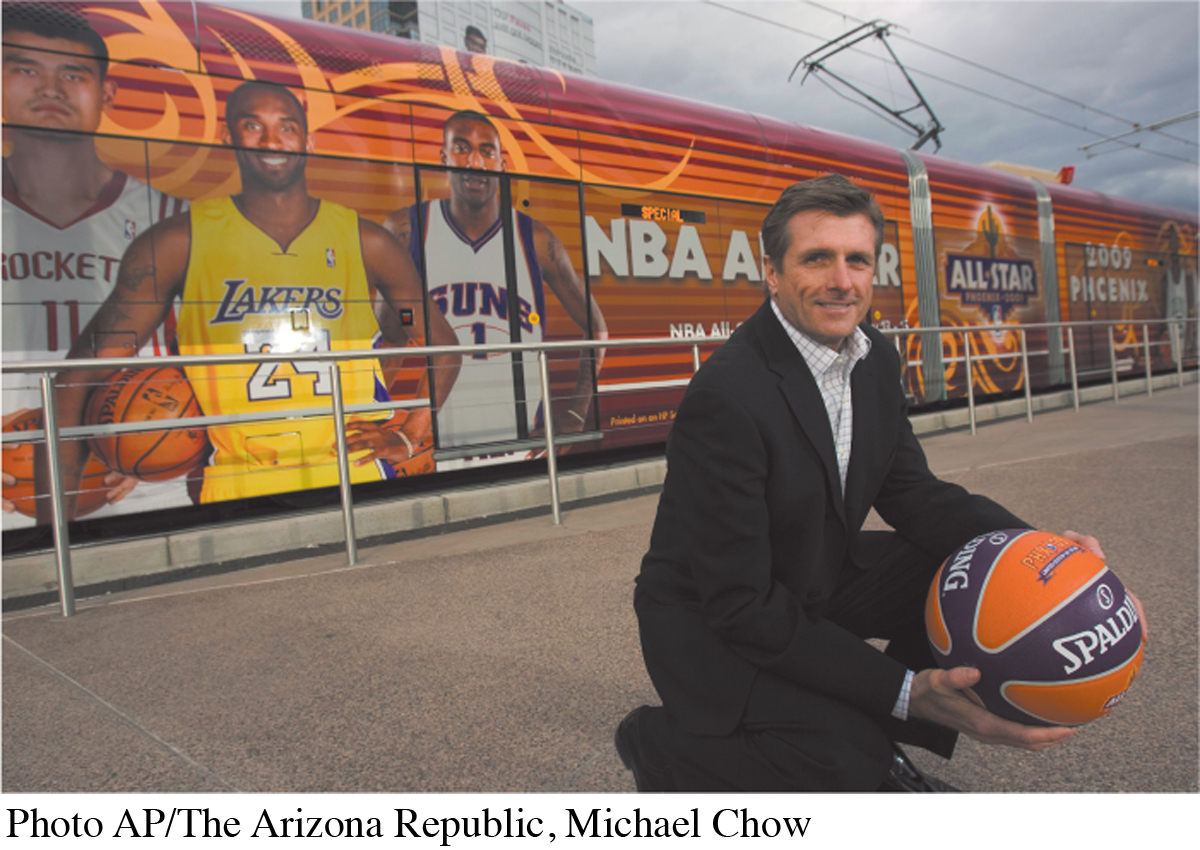

Rick Welts is one of the most influential people in professional basketball.2 He created the NBA All-Star Weekend and is cofounder of the women’s professional league, the WNBA. For years he served as the NBA’s executive vice president and chief marketing officer, and he is now president of the Golden State Warriors. But throughout his entire sports career—40 years of ascension from ball boy to executive—he lived a self-described “shadow life,” publicly playing the role of a straight male while privately being gay. The lowest point came when his longtime partner died and Welts couldn’t publicly acknowledge his loss. Instead, he took only two days off from work—telling colleagues that a friend had died—and for months compartmentalized his grief. In early 2011, following his mother’s death, he came out publicly. As Welts described, “I want to pierce the silence that envelops the subject of being gay in men’s team sports. I want to mentor gays who harbor doubts about a sports career, whether on the court or in the front office. But most of all, I want to feel whole, authentic.”

In addition to our private selves, the composite of our self-awareness, self-concept, and self-esteem, each of us also has a public self—the self we present to others (Fenigstein, Scheier, & Buss, 1975). We actively create our public selves through our interpersonal communication and behavior.

In many encounters, our private and public selves mirror each other. At other times, they seem disconnected. In extreme instances, like that of Rick Welts, we may intentionally craft an inauthentic public self to hide something about our private self we don’t want others to know. But regardless of your private self, it is your public self that your friends, family members, and romantic partners hold dear. Most (if not all) of others’ impressions of you are based on their appraisals of your public self. People know and judge the “you” who communicates with them, not the “you” you keep inside. Thus, managing your public self is a crucial part of competent interpersonal communication.

MAINTAINING YOUR PUBLIC SELF

Renowned sociologist Erving Goffman (1955) noted that whenever you communicate with others, you present a public self—your face—that you want others to see and know. You actively create and present your face through your communication. Your face can be anything you want it to be—“perky and upbeat,” “cool and level-headed,” or “tough as nails.” We create different faces for different moments and relationships in our lives, such as our face as a parent, college student, coworker, or homeless-shelter volunteer.

Sometimes your face is a mask, a public self designed to strategically veil your private self (Goffman, 1959). Masks can be dramatic, such as when Rick Welts hid his grief over the loss of his longtime partner. Or masks can be subtle—the parent who acts calm in front of an injured child so the youngster doesn’t become frightened. Some masks are designed to inflate one’s estimation in the eyes of others. One study found that 90 percent of college students surveyed admitted telling at least one lie to impress a person they were romantically interested in (Rowatt, Cunningham, & Druen, 1998). Other masks are crafted so that people underestimate us and our abilities (Gibson & Sachau, 2000), like acting disorganized or unprepared before a debate in the hope that your opponent will let her guard down.

Regardless of the form our face takes—a genuine representation of our private self, or a mask designed to hide this self from others—Goffman argued that we often form a strong emotional attachment to our face because it represents the person we most want others to see when they communicate with and relate to us.

Sometimes after we’ve created a certain face, information is revealed that contradicts it, causing us to lose face (Goffman, 1955). Losing face provokes feelings of shame, humiliation, and sadness—in a word, embarrassment. For example, singer Katy Perry stakes her career on appearing glamorous, fashionable, and sexy. In December 2010, however, her then husband—comedian Russell Brand—tweeted a photo of her that contradicted her carefully crafted image: Perry just waking up, without makeup. The singer was understandably upset and embarrassed.

While losing face can cause intense embarrassment, this is not the only cost. When others see us lose face, they may begin to question whether the public self with which they’re familiar is a genuine reflection of our private self. For example, suppose your workplace face is “dedicated, hardworking employee.” You ask your boss if there’s extra work to be done, help fellow coworkers, show up early, stay late, and so forth. But if you tell your manager that you need your afternoon schedule cleared to work on an urgent report and then she sees you playing World of Warcraft on your computer, she’ll undoubtedly view your actions as inconsistent with your communication. Your face as the “hardworking employee” will be called into question, as will your credibility.

Because losing face can damage others’ impressions of you, maintaining face during interpersonal interactions is extremely important. How can you effectively maintain face?3 Use words and actions consistent with the face you’re trying to craft. From one moment to the next and from one behavior to the next, your interpersonal communication and behaviors must complement your face. Make sure your communication and behaviors mesh with the knowledge that others already have about you. If you say or do things that contradict what others know is true about you, they’ll see your face as false. For example, if your neighbor knows you don’t like him because a friend of yours told him so, he’s likely to be skeptical the next time you adopt the face of “friendly, caring neighbor” by warmly greeting him.

self-reflection

Recall an embarrassing interpersonal encounter. How did you try to restore your lost face? Were you successful? If you could relive the encounter, what would you say and do differently?

Finally, for your face to be maintained, your communication and behavior must be reinforced by objects and events in the surrounding environment—things over which you have only limited control. For example, imagine that your romantic partner is overseas for the summer, and you agree to video chat regularly. Your first scheduled chat is Friday at 5 p.m. But when you’re driving home Friday afternoon, your car breaks down. Making things worse, your phone goes dead because you forgot to charge it, so there is no way to contact your partner. By the time you get home and online, your partner has already signed off, leaving a perplexed message regarding your “neglect.” To restore face, you’ll need to explain what happened.

Of course, all of us fall from grace on occasion. What can you do to regain face following an embarrassing incident? Promptly acknowledge that the event happened, admit responsibility for any of your actions that contributed to the event, apologize for your actions and for disappointing others, and move to maintain your face again. Apologies are fairly successful at reducing people’s negative impressions and the anger that may have been triggered, especially when such apologies avoid excuses that contradict what people know really happened (Ohbuchi & Sato, 1994). People who deny their inconsistencies or who blame others for their lapses are judged much more harshly.

skillspractice

Apologizing

Creating a skillful apology

Watch for instances in which you offend or disappoint someone.

Acknowledge the incident and admit your responsibility, face-to-face (if possible) or by phone.

Apologize for any harm you have caused.

Avoid pseudo-apologies that minimize the event or shift accountability, like “I’m sorry you overreacted” or “I’m sorry you think I’m to blame.”

Express gratitude for the person’s understanding if he or she accepts your apology.

THE IMPORTANCE OF ONLINE SELF-PRESENTATION

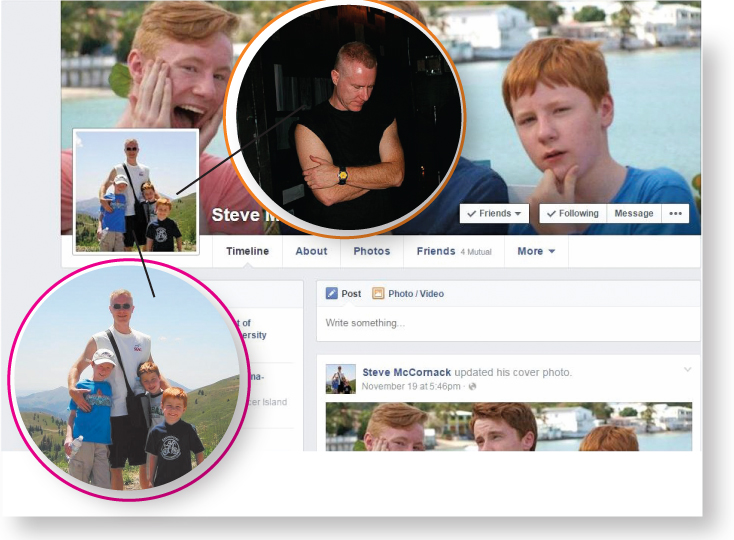

One of the most powerful vehicles for presenting your self online is your profile photo. Whether it’s on Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, Google, Tumblr, Flickr, Foursquare, or any other site, this image, more than any other, represents who you are to others. When I first built my Facebook profile, the photo I chose was one taken at a club, right before my band went onstage. For me, it depicted the “melancholy artist” that I consider part of my self-concept. But presenting my self online in this fashion was a disaster. Within hours of posting it, I was flooded with messages from students, colleagues, and even long-lost friends: “Are you OK?” “Did someone die?” I quickly pulled the photo and replaced it with a more positive one—a sunny image of me and my boys taken atop a mountain near Sun Valley. Now I use the melancholy photo only rarely, as accompaniment to a sad or an angry status update.

self-reflection

Have you ever distorted your self-presentation online to make yourself appear more attractive and appealing? If so, was this ethical? What were the consequences—for yourself and others—of creating this online mask?

Presenting the Self Online Online communication provides us with unique benefits and challenges for self-presentation. When you talk with others face-to-face, people judge your public self on your words as well as what you look like—your age, gender, clothing, facial expressions, and so forth. Similarly, during a phone call, vocal cues such as tone, pitch, and volume help you and your conversation partner draw conclusions about each other. But during online interactions, the amount of information communicated—visual, verbal, and nonverbal—is radically restricted and more easily controlled. We carefully choose our photos and edit our tweets, text messages, e-mail, instant messages, and profile descriptions. We selectively self-present in ways that make us look good, without having to worry about verbal slipups, uncontrollable nervous habits, or physical disabilities that might make people judge us (Parks, 2007).

People routinely present themselves online (through photos and written descriptions) in ways that amplify positive personality characteristics such as warmth, friendliness, and extraversion (Vazire & Gosling, 2004). For instance, photos posted on social networking sites typically show groups of friends, fostering the impression that the person in the profile is likable, fun, and popular (Ellison, Steinfield, & Lampe, 2007). These positive and highly selective depictions of self generally work as intended. Viewers of online profiles tend to form impressions of a profile’s subject that match the subject’s intended self-presentation (Gosling, Gaddis, & Vazire, 2007). So, for example, if you post profile photos and descriptions in an attempt to portray your self as “wild” and “hard partying,” this is the self that others will likely perceive.

The freedom that online communication allows us in flexibly crafting our selves comes with an associated cost: unless you have met someone in person, you will have difficulty determining whether their online self is authentic or a mask. Through misleading profile descriptions, fake photos, and phony screen names, people communicating online can assume identities that would be impossible for them to maintain in offline encounters (Rintel & Pittam, 1997). On online dating sites, for example, people routinely distort their self-presentations in ways designed to make them more attractive (Ellison, Heino, & Gibbs, 2006). Some people may also “gender swap” online, portraying themselves as female when they’re male, or vice versa—often by posting fake photos (Turkle, 1995). For this reason, scholars suggest that you should never presume the gender of someone you interact with online if you haven’t met the person face-to-face, even if he or she has provided photos (Savicki, Kelley, & Oesterreich, 1999).

Evaluating the Self Online Because of the pervasiveness of online masks, people often question the truthfulness of online self-presentations, especially overly positive or flattering ones. Warranting theory (Walther & Parks, 2002) suggests that when assessing someone’s online self-descriptions, we consider the warranting value of the information presented—that is, the degree to which the information is supported by other people and outside evidence (Walther, Van Der Heide, Hamel, & Schulman, 2008). Information that was obviously crafted by the person, that isn’t supported by others, and that can’t be verified offline has low warranting value, and most people wouldn’t trust it. Information that’s created or supported by others and that can be readily verified through alternative sources on- and offline has high warranting value and is consequently perceived as valid. So, for example, news about a professional accomplishment that you tweet or post on Facebook will have low warranting value. But if the same information is also featured on your employer’s Web site, its warranting value will increase (Walther et al., 2008). Similarly, photos you take and post of yourself will have less warranting value than similar photos of you taken and posted by others, especially if the photos are perceived as having been taken without your knowledge, such as candid shots (Walther et al., 2008).

Not surprisingly, the warranting value of online self-descriptions plummets when they are directly contradicted by others. Imagine that Jane, a student in your communication class, friends you on Facebook. Though you don’t know her especially well, you accept and, later, check out her page. In the content that Jane has provided, she presents herself as quiet, thoughtful, and reserved. But messages from her friends on her Facebook timeline contradict this, saying things like, “You were a MANIAC last night!” and “u r a wild child!” Based on this information, you’ll likely disregard Jane’s online self-presentation and judge her instead as sociable and outgoing, perhaps even “crazy” and “wild.”

Research shows that when friends, family members, coworkers, or romantic partners post information on your page, their messages shape others’ perceptions of you more powerfully than your own postings do, especially when their postings contradict your self-description (Walther et al., 2008). This holds true not just for personality characteristics such as extraversion (how outgoing you are) but also for physical attractiveness. One study of Facebook profiles found that when friends posted things like, “If only I was as hot as you” or (alternatively) “Don’t pay any attention to those jerks at the bar last night; beauty is on the inside,” such comments influenced others’ perceptions of the person’s attractiveness more than the person’s own description of his or her physical appeal (Walther et al., 2008).

skillspractice

Your Online Self

Maintaining your desired online face

Describe your desired online face (e.g., “I want to be seen as popular, adventurous, and attractive”).

Critically compare this description with your profiles, photos, and posts. Do they match?

Revise or delete content that doesn’t match your desired face.

Repeat this process for friends’ postings on your personal pages.

In your future online communication—tweeting, texting, e-mailing, and posting—present yourself only in ways that mesh with your desired face.

IMPROVING YOUR ONLINE SELF-PRESENTATION

Taken as a whole, the research and theory about online self-presentation suggests three practices for improving your online self-presentation. First, keep in mind that online communication is dominated by visual information, such as text, photos, and videos. Make wise choices in the words and images you select to present yourself to others. For example, many women managers know they’re more likely than their male peers to be judged solely on appearance, so they post photos of themselves that convey professionalism (Miller & Arnold, 2001).

Second, always remember the important role that warranting value plays in shaping others’ impressions of you. The simple rule is that what others say about you online is more important than what you say about your self. Consequently, be wary of allowing messages and timeline postings on your personal Web pages that contradict the self you want to present, or that cast you in a negative light—even if you think such messages and postings are cute, funny, or provocative. If you want to track what others are posting about you away from your personal pages, set up a Google Alert or regularly search for your name and other identifying keywords. This will allow you to see what information, including photos, others are posting about you online. When friends, family members, coworkers, or romantic partners post information about you that disagrees with how you wish to be seen, you can (politely) ask them to delete it.

Finally, subject your online self-presentation to what I call the interview test: ask yourself, Would I feel comfortable sharing all elements of this presentation—photos, personal profiles, videos, blogs—in a job interview? If your answer is no, modify your current online self-presentation immediately. In a survey of 1,200 human resources professionals and recruiters, 78 percent reported using search engines to screen candidates, while 63 percent reported perusing social networking sites (Balderrama, 2010).