The Relational Self

One of the reasons we carefully craft the presentation of our self is to create interpersonal relationships. We present our self to acquaintances, coworkers, friends, family members, and romantic partners, and through our interpersonal communication, relationships are fostered, maintained, and sometimes ended. Within each of these relationships, how close we feel to one another is defined largely by how much of our self we reveal to others, and vice versa.

Managing the self in interpersonal relationships isn’t easy. Exposing our self to others can make us feel vulnerable, provoking tension between how much to reveal versus how much to veil. Even in the closest of relationships, certain aspects of the self remain hidden—from our partners as well as ourselves.

OPENING YOUR SELF TO OTHERS

In the movie Shrek, the ogre Shrek forges a friendship with a likable but occasionally irksome donkey (Adamson & Jenson, 2001). As their acquaintanceship deepens to friendship, Shrek tries to explain the nature of his inner self to his companion:

SHREK: For your information, there’s a lot more to ogres than people think!

DONKEY: Example . . . ?

SHREK: Example . . . OK . . . Um . . . Ogres . . . are like onions.

DONKEY: They stink?

SHREK: Yes . . . NO!

DONKEY: Or they make you cry?

SHREK: No!

DONKEY: Oh . . . You leave ’em out in the sun and they get all brown and start sprouting little white hairs!

SHREK: No! Layers! Onions have layers—OGRES have layers! Onions have layers! You get it!? We both have layers!

DONKEY: Ooohhhh . . . you both have layers . . . oh. You know, not everybody likes onions . . . CAKE! Everybody loves cakes! Cakes have layers!

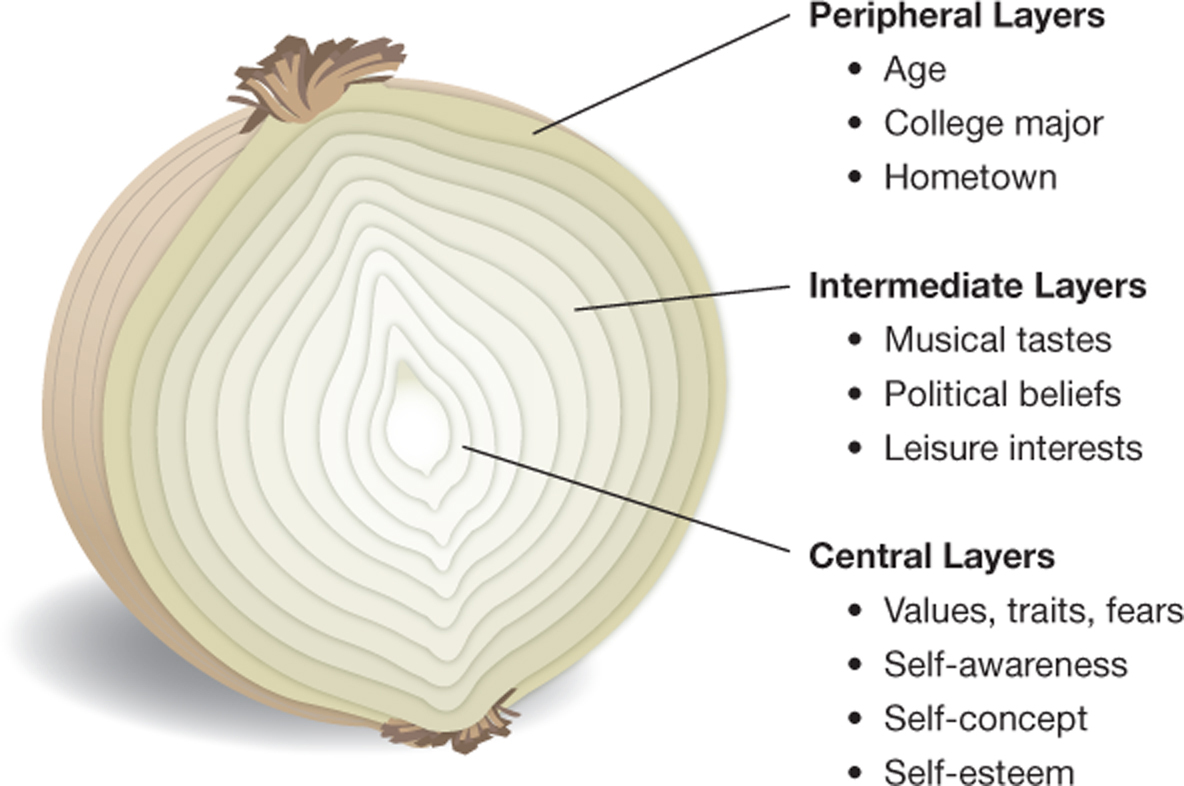

Shrek was not the first to use the onion as a metaphor for self. In fact, the idea that revealing the self to others involves peeling back or penetrating layers was first suggested by psychologists Irwin Altman and Dalmas Taylor (1973) in their social penetration theory. Like Shrek, Altman and Taylor envisioned the self as an “onion-skin structure,” consisting of sets of layers.4

At the outermost, peripheral layers of your self are demographic characteristics such as birthplace, age, gender, and ethnicity (see Figure 2.2). Discussion of these characteristics dominates first conversations with new acquaintances: What’s your name? What’s your major? Where are you from? In the intermediate layers reside your attitudes and opinions about music, politics, food, entertainment, and other such matters. Deep within the “onion” are the central layers of your self—core characteristics such as self-awareness, self-concept, self-esteem, personal values, fears, and distinctive personality traits. We’ll discuss these in more detail in Chapter 3.

The notion of layers of self helps explain the development of interpersonal relationships, as well as how we distinguish between casual and close involvements. As relationships progress, partners communicate increasingly personal information to each other. This allows them to mutually penetrate each other’s peripheral, then intermediate, and finally central selves. Relationship development is like slowly pushing a pin into an onion: it proceeds layer by layer, without skipping layers.

The revealing of selves that occurs during relationship development involves both breadth and depth. Breadth is the number of different aspects of self each partner reveals at each layer—the insertion of more and more pins into the onion, so to speak. Depth involves how deeply into each other’s self the partners have penetrated: have you revealed only your peripheral self, or have you given the other person access into your intermediate or central selves as well?

Although social penetration occurs in all relationships, the rate at which it occurs isn’t consistent. For example, some people let others in quickly, while others never grant access to certain elements of their selves no matter how long they know a person. The speed with which people grant each other access to the broader and deeper aspects of their selves depends on a variety of factors, including the attachment styles discussed earlier in the chapter. But in all relationships, depth and breadth of social penetration is intertwined with intimacy: the feeling of closeness and “union” that exists between us and our partners (Mashek & Aron, 2004). The deeper and broader we penetrate into each other’s selves, the more intimacy we feel; the more intimacy we feel, the more we allow each other access to broad and deep aspects of our selves (Shelton, Trail, West, & Bergsieker, 2010).

YOUR HIDDEN AND REVEALED SELF

The image of self and relationship development offered by social penetration theory suggests a relatively straightforward evolution of intimacy, with partners gradually penetrating broadly and deeply into each other’s selves over time. But in thinking about our selves and our relationships with others, two important questions arise: First, are we really aware of all aspects of our selves? Second, are we willing to grant others access to all aspects of our selves?

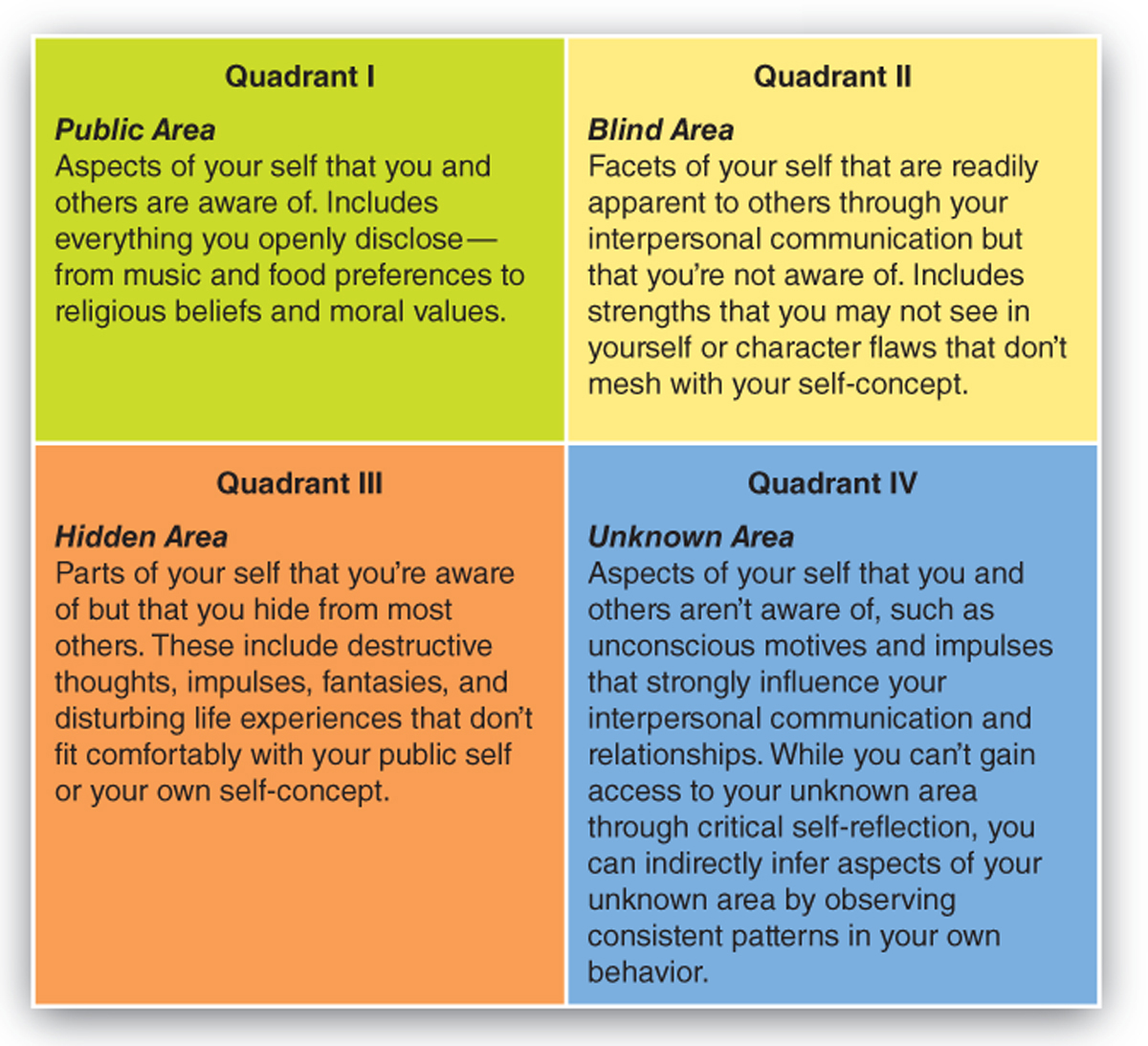

We can explore possible answers to these questions by looking at the model of the relational self called the Johari Window (see Figure 2.3), which suggests that some “quadrants” of our selves are open to self-reflection and sharing with other people, while others remain hidden—to both ourselves and others.

self-reflection

Consider your “blind area” of self. What strengths might you possess that you don’t recognize? What character flaws might exist that don’t mesh with your self-concept? How can you capitalize on these strengths and mend your flaws so that your interpersonal communication and relationships improve?

During the early stages of an interpersonal relationship and especially during first encounters, our public area of self is much smaller than our hidden area. As relationships progress, partners gain access to broader and deeper information about their selves; consequently, the public area expands, and the hidden area diminishes. The Johari Window provides us with a useful alternative metaphor to social penetration. As relationships develop, we don’t just let people “penetrate inward” to our central selves; we let them “peer into” more parts of our selves by revealing information that we previously hid from them.

As our interpersonal relationships develop and we increasingly share previously hidden information with our partners, our unknown and blind quadrants remain fairly stable. By their very nature, our unknown areas remain unknown throughout much of our lives. And for most of us, the blind area remains imperceptible. That’s because our blind areas are defined by our deepest-rooted beliefs about ourselves—those beliefs that make up our self-concepts. Consequently, when others challenge us to open our eyes to our blind areas, we resist.

To improve our interpersonal communication, we must be able to see into our blind areas and then change the aspects within them that lead to incompetent communication and relationship challenges. But this isn’t easy. After all, how can you correct misperceptions about yourself that you don’t even know exist or flaws that you consider your greatest strengths? Delving into your blind area means challenging fundamental beliefs about yourself—subjecting your self-concept to hard scrutiny. The goal of this is to overturn your most treasured personal misconceptions. Most people accomplish this only over a long period of time and with the assistance of trustworthy and willing relationship partners.