Perception as a Process

In the movie Inception, Dom Cobb—played by Leonardo DiCaprio—enters others’ unconscious minds while they’re asleep and steals their thoughts. Since living inside others’ dreams can lead one to confuse dream states with reality, Cobb has a totem that he keeps with him always—a toy top that allows him to tell quickly whether he’s dreaming or awake. When he is within a dream state, the top spins endlessly, whereas when he is awake, it spins for a few moments, then wobbles and falls.

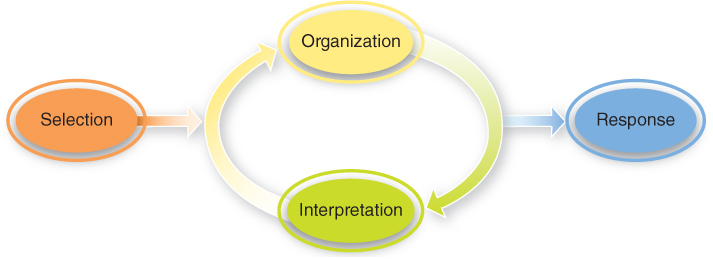

Like Dom Cobb, each of us has a totem we trust to tell us what’s real and what isn’t: our perception. Perception is the process of selecting, organizing, and interpreting information from our senses. We rely on perception constantly to make sense of everything and everyone in our environment. Perception begins when we select information on which to focus our attention. We then organize the information into an understandable pattern inside our minds and interpret its meaning. Each activity influences the other: our mental organization of information shapes how we interpret it, and our interpretation of information influences how we mentally organize it. (See Figure 3.1) Let’s take a closer look at the perception process.

SELECTING INFORMATION

It’s finals week, and you’re in your room studying for a difficult exam. Exhausted, you decide to take a break and listen to some music. You don your headphones, press play, and close your eyes. Suddenly you hear a noise. Startled, you open your eyes and remove your headphones to find that your housemate has just yanked open your bedroom door. “I’ve been yelling at you to pick up your phone for the last five minutes,” she snaps. “What’s going on?!”

The first step of perception, selection, involves focusing attention on certain sights, sounds, tastes, touches, or smells in our environment. Consider the housemate example. Once you hear her enter, you would likely select her communication as the focus of your attention. The degree to which particular people or aspects of their communication attract our attention is known as salience (Fiske & Taylor, 1991). When something is salient, it seems especially noticeable and significant. We view aspects of interpersonal communication as salient under three conditions (Fiske & Taylor, 1991). First, communication is salient if the communicator behaves in a visually and audibly stimulating fashion. A housemate yelling and energetically gesturing is more salient than a quiet, motionless housemate. Second, communication becomes salient if our goals or expectations lead us to view it as significant. Even a housemate’s softly spoken phone announcement will command our attention if we are anticipating an important call. Last, communication that deviates from our expectations is salient. An unexpected verbal attack will always be more salient than an expected one.

ORGANIZING THE INFORMATION YOU’VE SELECTED

Once you’ve selected something as the focus of your attention, you take that information and structure it into a coherent pattern in your mind, a phase of the perception process known as organization (Fiske & Taylor, 1991). For example, imagine that a cousin is telling you about a recent visit to your hometown. As she shares her story with you, you select certain bits of her narrative on which to focus your attention based on salience, such as a mutual friend she saw during her visit or a favorite old hangout she went to. You then organize your own representation of her story inside your head.

During organization, you engage in punctuation, structuring the information you’ve selected into a chronological sequence that matches how you experienced the order of events (Watzlawick, Beavin, & Jackson, 1967). To illustrate punctuation, think about how you might punctuate the sequence of events in our housemate example. You hear a noise, open your eyes, see your housemate in your room, and then hear her yelling at you. But two people involved in the same interpersonal encounter may punctuate it in very different ways. Your housemate might punctuate the same incident by noting that your ringing cell phone in the common area was disrupting her studying, and despite her efforts to get your attention, you never responded.

If you and another person organize and punctuate information from an encounter differently, the two of you may well feel frustrated with each other. Disagreements about punctuation, and especially disputes about who started unpleasant encounters, are a common source of interpersonal conflict (Watzlawick et al., 1967). For example, your housemate may contend that “you started it” because she told you to get your phone but you ignored her. You may believe that “she started it” because she barged into your room without knocking.

We can avoid perceptual misunderstandings that lead to conflict by understanding how our organization and punctuation of information differ from those of other people. One helpful way to forestall such conflicts is to practice asking others to share their views of encounters. You might say, “Here’s what I saw, but that’s just my perspective. What do you think happened?”

INTERPRETING THE INFORMATION

As we organize information we have selected into a coherent mental model, we also engage in interpretation, assigning meaning to that information. We call to mind familiar information that’s relevant to the current encounter, and we use that information to make sense of what we’re hearing and seeing. We also create explanations for why things are happening as they are.

self-reflection

Recall a conflict in which you and a friend disagreed about “who started it.” How did you punctuate the encounter? How did your friend punctuate it? If each of you punctuated differently, how did those differences contribute to the conflict? If you could revisit the situation, what might you say or do differently to resolve the dispute?

Using Familiar Information We make sense of others’ communication in part by comparing what we currently perceive with knowledge that we already possess. For example, I proposed to my wife by surprising her after class. I had decorated her apartment with several dozen roses and carnations, was dressed in my best (and only!) suit, and was spinning “our song” on her turntable—the Spinners’ “Could It Be I’m Falling in Love.” When she opened the door and I asked her to marry me, she immediately interpreted my communication correctly. But how, given that she had never been proposed to before? Because she knew from friends, family members, movies, and television shows what a marriage proposal looks and sounds like. Drawing on this familiar information, she correctly figured out what I was up to and (thank goodness!) accepted my proposal.

The knowledge we draw on when interpreting interpersonal communication resides in schemata, mental structures that contain information defining the characteristics of various concepts, as well as how those characteristics are related to each other (Macrae & Bodenhausen, 2001). Each of us develops schemata for individual people, groups of people, places, events, objects, and relationships. In the previous example, my wife had a schema (the singular form of schemata) for “marriage proposal,” and that enabled her to correctly interpret my actions.

Because we use familiar information to make sense of current interactions, our interpretations reflect what we presume to be true. For example, suppose you’re interviewing for a job with a manager who has been at the company for 18 years. You’ll likely interpret everything she says in light of your knowledge about “long-term employees.” This knowledge includes your assumption that “company veterans generally know insider information.” So, when your interviewer talks in glowing terms about the company’s future, you’ll probably interpret her comments as credible. Now imagine that you receive the same information from someone who has been with the company only a few weeks. Based on your perception of him as “new employee” and on the information you have in your “new employee” schema, you may interpret his message as naïve speculation rather than expert commentary, even if his statements are accurate.

Creating Explanations In addition to drawing on our schemata to interpret information from interpersonal encounters, we create explanations for others’ comments or behaviors, known as attributions. Attributions are our answers to the why questions we ask every day. “Why didn’t my partner return my text message?” “Why did my best friend share that horrible, embarrassing photo of me on Instagram?”

Consider an example shared with me by a friend, Sarah. She had finished teaching for the semester and was out of town and off line for a week. When she returned home and logged on to her e-mail, she found a week-old note from Janet, a student who had failed her course, asking Sarah if there was anything she could do to improve her grade. She also found a second e-mail from Janet, dated a few days later, accusing Sarah of ignoring her:

From: Janet [mailto:janet@school.edu]

Sent: Friday, May 15, 2015 10:46 AM

To: Professor Sarah

Subject: FW: Grade

Maybe my situation isn’t a priority to you, and that’s fine, but a response e-mail would’ve been appreciated! Even if all you had to say was “there’s nothing I can do.” I came to you seeking help, not a hand-out!—Janet.2

Put yourself in Janet’s shoes for a moment. What attributions did Janet make about Sarah’s failure to respond? How did these attributions shape Janet’s communication in her second e-mail? Now consider this situation from Sarah’s perspective. If you were in her shoes, what attributions would you make about Janet, and how would they shape how you interpreted her e-mail?

Attributions take two forms, internal and external (see Table 3.1). Internal attributions presume that a person’s communication or behavior stems from internal causes, such as character or personality. For example, “My professor didn’t respond to my e-mail because she doesn’t care about students” or “Janet sent this message because she’s rude.” External attributions hold that a person’s communication is caused by factors unrelated to personal qualities: “My professor didn’t respond to my e-mail because she hasn’t checked her messages yet” or “Janet sent this message because I didn’t respond to her first message.”

| Communication Event | Internal Attribution | External Attribution |

|---|---|---|

| Your romantic partner doesn’t reply after you send a flirtatious text message. | “My partner doesn’t care about me.” | “My partner is probably too busy to respond.” |

| Your unfriendly coworker greets you warmly. | “My coworker is friendlier than I thought.” | “Something unusual must have happened to make my coworker act so friendly.” |

| Your friend ridicules your taste in music. | “My friend has an unpredictable mean streak.” | “My friend must be having a really bad day.” |

Like schemata, the attributions we make influence powerfully how we interpret and respond to others’ communication. For example, if you think Janet’s e-mail was caused by her having a terrible day, you’ll likely interpret her message as an understandable venting of frustration. If you think her message was caused by her personal rudeness, you’ll probably interpret the e-mail as inappropriate and offensive.

self-reflection

Recall a fight you’ve had with parents or other family members. Why did they behave as they did? What presumptions did they make about you and your behavior? When you assess both your and their attributions, are they internal or external? What does this tell you about the power and prevalence of the fundamental attribution error?

Given the dozens of people with whom we communicate each day, it’s not surprising that we often form invalid attributions. One common mistake is the fundamental attribution error, the tendency to attribute others’ behaviors solely to internal causes (the kind of person they are) rather than to the social or environmental forces affecting them (Heider, 1958). For example, communication scholar Alan Sillars and his colleagues found that during conflicts between parents and teens, both parties fall prey to the fundamental attribution error (Sillars, Smith, & Koerner, 2010). Parents commonly attribute teens’ communication to “lack of responsibility” and “desire to avoid the issue,” whereas teens attribute parents’ communication to “desire to control my life.” All these assumptions are internal causes. These errors make it harder for teens and parents to constructively resolve their conflicts, something we discuss more in Chapter 9.

The fundamental attribution error is so named because it is the most prevalent of all perceptual biases, and each of us falls prey to it (Langdridge & Butt, 2004). Why does this error occur? Because when we communicate with others, they dominate our perception. They—not the surrounding factors that may be causing their behavior—are most salient for us. Consequently, when we make judgments about why someone is acting in a certain way, we overestimate the influence of the person and underestimate the significance of his or her immediate environment (Heider, 1958; Langdridge & Butt, 2004).

skillspractice

Improving Online Attributions

Improving your attributions while communicating online

Identify a negative tweet, text, e-mail, or Web posting you’ve received.

Consider why the person sent the message.

Write a response based on this attribution, and save it as a draft.

Think of and list other possible, external causes for the person’s message.

Keeping these alternative attributions in mind, revisit and reevaluate your response draft, editing it as necessary to ensure competence before you send or post it.

The fundamental attribution error is especially common during online interactions (Shedletsky & Aitken, 2004). Because we aren’t privy to the rich array of environmental factors that may be shaping our communication partners’ messages—all we perceive is words on a screen—we’re more likely to interpret others’ communication as stemming solely from internal causes (Wallace, 1999). As a consequence, when a tweet, text message, Facebook post, e-mail, or chat message is even slightly negative in tone, we’re very likely to blame that negativity on bad character or personality flaws. Such was the case when Sarah presumed that Janet was a rude person based on her e-mail.

A related error is the actor-observer effect, the tendency of people to make external attributions regarding their own behaviors (Fiske & Taylor, 1991). Because our mental focus during interpersonal encounters is on factors external to us—especially the person with whom we’re interacting—we tend to credit these factors as causing our own communication. This is particularly prevalent during unpleasant interactions. Our own impolite remarks during family conflicts, for example, are viewed as “reactions to their hurtful communication” rather than “messages caused by our own insensitivity.”

However, we don’t always make external attributions regarding our own behaviors. In cases in which our actions result in noteworthy success, either personal or professional, we typically take credit for the success by making an internal attribution, a tendency known as the self-serving bias (Fiske & Taylor, 1991). Suppose you’ve successfully persuaded a friend to lend you her car for the weekend. In this case, you will probably attribute this success to your charm and persuasive skill rather than to luck or your friend’s generosity. The self-serving bias is driven by ego protection: by crediting ourselves for our life successes, we can feel happier about who we are.

Clearly, attributions play a powerful role in how we interpret communication. For this reason, it’s important to consider the attributions you make while you’re interacting with others. Check your attributions frequently, watching for the fundamental attribution error, the actor-observer effect, and the self-serving bias. If you think someone has spoken to you in an offensive way, ask yourself if it’s possible that outside forces—including your own behavior—could have caused the problem. Also keep in mind that communication (like other forms of human behavior) rarely stems from only external or internal causes. It’s caused by a combination of both (Langdridge & Butt, 2004).

Finally, when you can, check the accuracy of your attributions by asking people for the reasons behind their behavior. When you’ve made attribution errors that lead you to criticize or lose your patience with someone else, apologize and explain your mistake to the person. After Janet learned that Sarah hadn’t responded because she had been out of town and offline, Janet apologized. She also explained why her message was so terse: she thought Sarah was intentionally ignoring her. Upon receiving Janet’s apology, Sarah apologized also. She realized that she, too, had succumbed to the fundamental attribution error by wrongly presuming that Janet was a rude person.

REDUCING UNCERTAINTY

When intercultural communication scholar Patricia Covarrubias (2000) was a young girl, she and her family immigrated to the United States from Mexico. On her first day of school in her adoptive country, Patricia’s third-grade teacher, Mrs. Williams, led her to the front of the classroom to introduce her to her new classmates. Growing up in Mexico, her friends and family called her la chiquita (the little one) or mi Rosita de Jerico (my rose of Jericho), but in the more formal setting of the classroom, Patricia expected her teacher to introduce her as Patricia Covarrubias, or perhaps Patricia. Instead, Mrs. Williams, her hand gently resting on Patricia’s shoulder, turned to the class and said, “Class, this is Pat.”

Patricia was dumbfounded. In her entire life, she had never been Pat, nor could she understand why someone would call her Pat. As she explains, “In one unexpected moment, all that I was and had been was abridged into three-letter, bottom-line efficiency” (Covarrubias, 2000, pp. 10–11). And although Mrs. Williams was simply trying to be friendly—using an abbreviation most Euro-Americans would consider informal—Patricia was mortified. The encounter bolstered her feeling that she was an outsider in an uncertain environment.

In most interpersonal interactions, the perception process unfolds in a rapid, straightforward manner. But sometimes we find ourselves in situations in which people communicate in perplexing ways. In such contexts, we experience uncertainty, the anxious feeling that comes when we can’t predict or explain someone else’s communication.

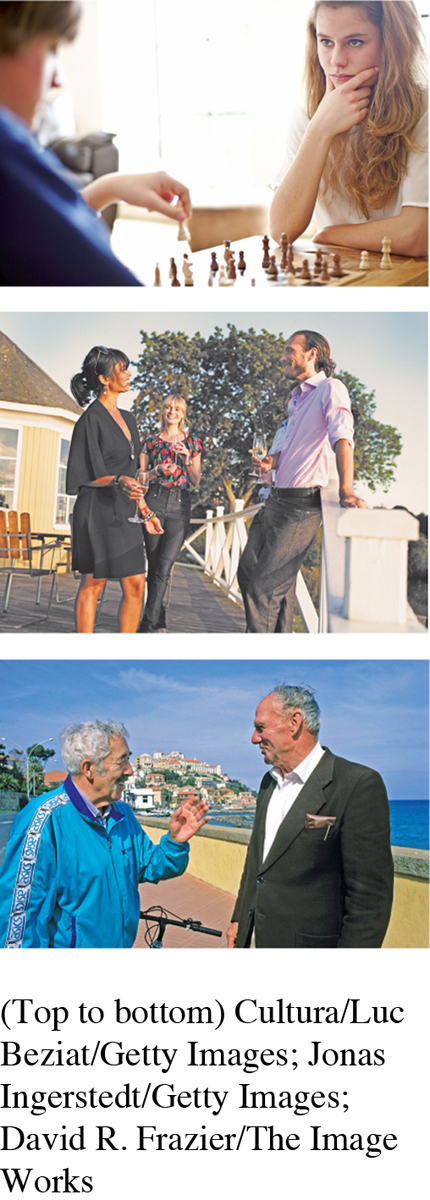

Uncertainty is common during first encounters with new acquaintances, when we don’t know much about the people with whom we’re communicating. According to Uncertainty Reduction Theory, our primary compulsion during initial interactions is to reduce uncertainty about our communication partners by gathering enough information about them that their communication becomes predictable and explainable (Berger & Calabrese, 1975). When we reduce uncertainty, we’re inclined to perceive people as attractive and likable, talk further, and consider forming relationships with them (Burgoon & Hoobler, 2002).

self-reflection

When do you use passive strategies to reduce your uncertainty? active strategies? interactive strategies? Which do you prefer, and why? What ethical concerns influence your own use of passive and active strategies?

Uncertainty can be reduced in several ways, each of which has advantages and disadvantages (Berger & Bradac, 1982). First, you can observe how someone interacts with others. Known as passive strategies, these approaches can help you predict how he or she may behave when interacting with you, reducing your uncertainty. Examples include observing someone hanging out with friends at a party or checking out someone’s Facebook profile. Second, you can try active strategies by asking other people questions about someone you’re interested in. You might find someone who knows the person you’re assessing and then get him or her to disclose as much information as possible about that individual. Be aware, though, that this poses risks: the target person may find out that you’ve been asking questions. That could embarrass you and upset the target. In addition, third-party information may not be accurate. Third, and perhaps most effective, are interactive strategies: starting a direct interaction with the person you’re interested in. Inquire where the person is from, what he or she does for a living, and what interests he or she has. You should also disclose personal information about yourself. This enables you to test the other person’s reactions to you. Is the person intrigued or bored? That information can help you reduce your uncertainty about how to communicate further.